The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Finnish artist Kirsi Mikkola gained recognition in the 1990s for her colorful, cartoonish plaster sculptures. In recent years she went through a radical shift in her artistic practice in developing a distinct approach to abstraction that merges the formal language of painting and collage that Mikkola herself refers to as “constructions”. Today she is one of the most important Finnish artists. With studios in Vienna and Berlin, Kirsi Mikkola is also a professor of painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Rising star Amoako Boafo was a student in her class at the academy.

Kirsi, how did you come to art?

I left Helsinki early, and went first to New York where I studied theater, with the intention of becoming a theater director, but the theater world there was too sexist for me. At that time I was already painting, and people told me: “Hey, why don’t you become an artist, you’re so talented after all?” And I thought: “No way!” I didn’t want to enter the fate of eternal loneliness voluntarily, it was too threatening for me. But ultimately that’s how it turned out and I studied art at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. At some point, however, I felt that life in France was too arbitrary for me. I needed a different inspiration. So I came to Berlin.

What fascinated you about Berlin?

The whole city had such an anarchistic atmosphere and I found it very bold and at the same time very attractive. Everyone was talking about Berlin back then, the city was so brutal and violent, right now we find ourselves in a time of change; at that time I was impressed by the attitude of Berliners. I studied painting for seven years at the UdK with Marwan Kassab-Bachi, and in between I spent a year in London on an Erasmus scholarship. I had a place offered by both the Royal College and the Slade, but I felt that gave me nothing. Furthermore, I found the people there to be dishonest and conceited, still caught up in their colonialist past and rigid class structure, just boring. Therefore I returned to Berlin, although it was much nicer in England, but I didn’t want nice. Since then I have been living both in Berlin and in Vienna, it is a perfect combination for me, and I travel with my passion in my luggage to the academy in Vienna.

Where does this passion originate? You have a reputation for being a true bundle of energy. Artists including Amoako Boafo, who studied with you at the Academy in Vienna, say that your class has a very good energy. One can see that here in your paintings as well.

This is my character, I pull this from nowhere. It comes from within. My energy is my wealth, it is the only thing I have. In art it is exactly what I think it has to be. You have to put this devotion into your work, and best of all, you have to do it in such a way that it can be felt almost in an epic way, not as a play, but as a visual quality; and I feel dedicated to that. And I share this passion and this personal asset that I possess with great pleasure. You could also say the “inner richness”, but that sounds a little trite. And I think it contains a great substance, it is not superficial. It gives a quality to existence.

In the 1990s you were known for your colorful, caricature-like plaster sculptures. Why did you start with sculptures although you had studied painting?

I have been successful with my sculptures and have been in conversation with some important galleries about them, but I first studied painting, that’s true and that was my path. That was actually my path. But the feeling came up in me that as a painter I would never be able to gain a place in this man’s world, no matter how good I was. I had the feeling that the world of painting that really interested me, be it Willem de Kooning or all the other physical painters, would remain closed to me as a woman. I found that very hard, and I really wanted to let out my anger about it, which went down very well of course, and out of this motivation, I began with the sculptures. That was right after my studies. I thought I couldn’t hear my voice, and that the world didn’t need another mediocre expressionist, or someone pseudo-intellectualizing about some kind of canon, such things do not Interest me, I think art is much bigger, for everyone, regardless of whether it be for a man or a woman. Then the sculptures got out of hand.

Was this the moment when you withdrew from art for a while?

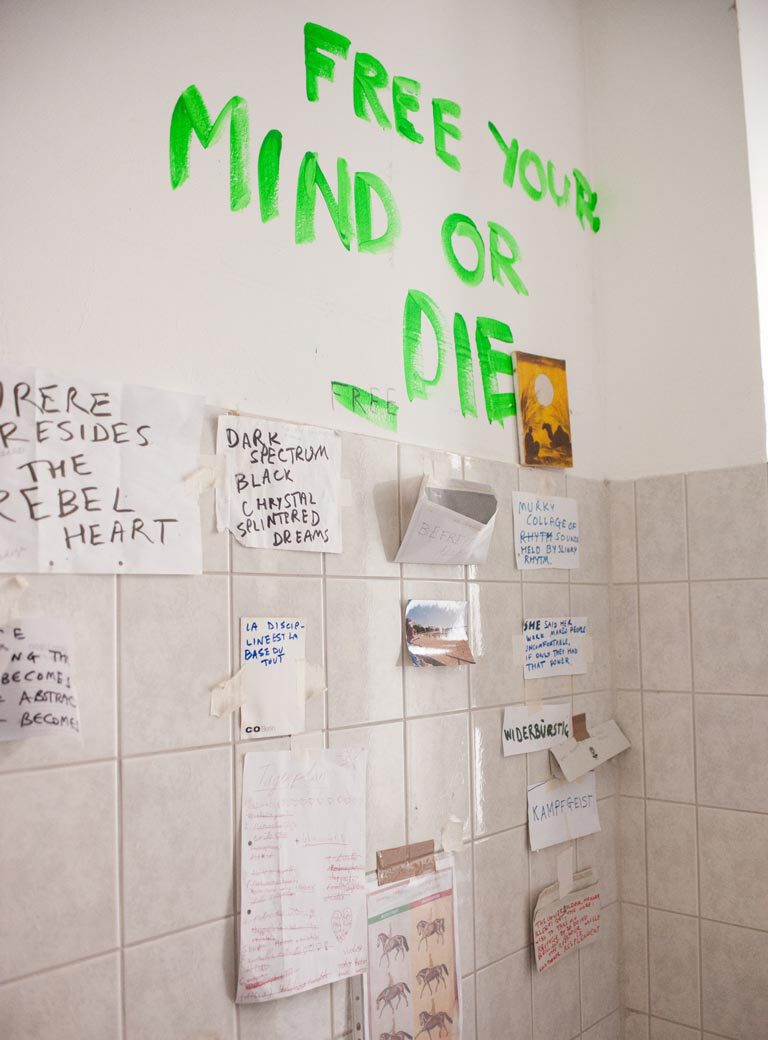

Yes, that was around 2000. I felt robbed of my artistic freedom. The art world around me claimed, “People know you like this now, you have to keep working like this!” And I said, “They don't know me at all!” and I removed myself. For me, from an artistic point of view, the theme of feminism contained in my sculptures was simply closed at a certain point. I deliberately let go of the “great career” that was forecast for me with feminist art, because I would have had to sell my soul for it. I made a statement at that time which I don’t want to get out and polish again, as I have said all there is to say about it. I can only somehow put it into another form, but that doesn’t make it more interesting, because it’s already there. I didn’t become an artist in order to let myself be determined by any ideology. That would destroy the freedom with which I was born as a human being. I will not let myself be instrumentalized. And that’s why I simply let the whole art market go. It doesn’t interest me. Then there was a break, which lasted ten years.

A ten-year break from the art world – that is courageous. What did you do during that time?

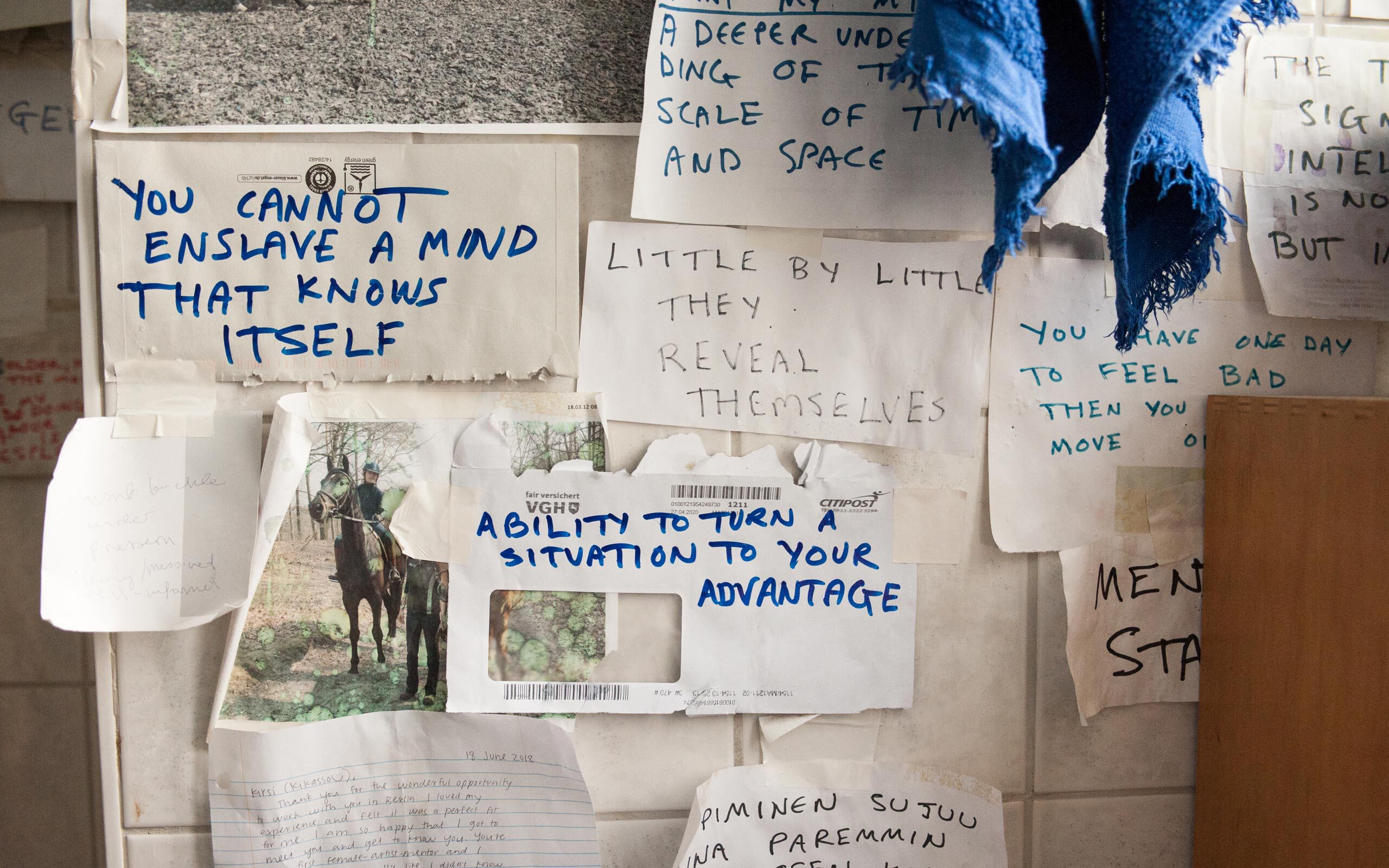

During my time out I started to occupy myself with nature and especially with horses. At times I wanted to do something completely different, I wanted to become a judge, for example, because I thought the profession suited my thinking much better. I wanted to run away from art, but it pursued me. I had withdrawn and simply tried to do something in quiet peace, where I had an authentic feeling that something interesting for me was at stake.

How did it continue artistically for you after your time out?

From the very beginning, it was clear to me that if I were to overcome this blockade with feminism in my head, then access to art would open up again for me. I have always felt that. I have always loved painting and all its freedom. Daring to go back there, was really difficult. But it was the only thing that was right for me and felt good. And that’s why after the break I continued with painting. Meeting my former gallerist, Ulrich Gebauer, again by chance after quite some time, was a beautiful moment between us. Although I hadn’t seen him for so long we had a very good conversation and he invited me to show him new work. Four months later, I went back to him with a garbage bag full of artworks and he thought they were great and intense. That was touching for me. A couple of nice exhibitions followed.

Let’s jump into the now: Your works are scattered all over the floor and one can’t walk through your studio without almost stepping on them. Is that part of your artistic process? How do you start with a painting?

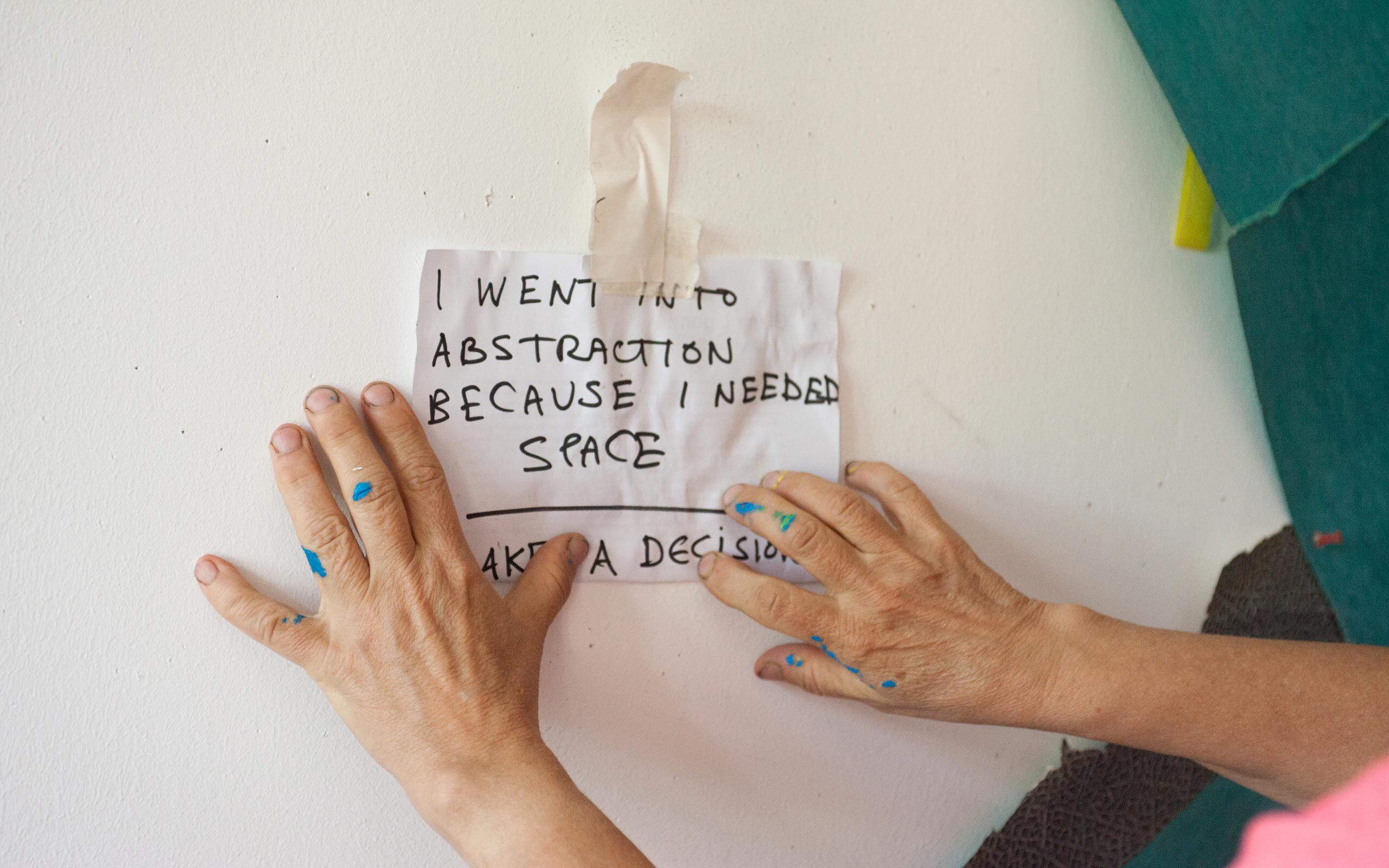

I have to be fully immersed in the work process. And if it’s good, then it’s an undertow, and I have to stay in it. That is the creative process. And I can’t want much of the things: Either they give themselves up and keep opening the door, or it remains on a superficial level. Then it has to go. And that is a very interesting challenge. For me, a good picture is the absolutely most difficult thing in life. And that is why it fascinates me so much. The pictures are living beings in their own right. First I paint papers with color as the ones that are lying around everywhere. The main thing is that there is a lot of visual stuff around me. Then I take parts of the papers and reassemble them so that very different shapes emerge, small ones, large ones, there is everything.

I know you don’t like the term collage. Instead, you prefer the word “construction”. What would you call your artistic approach today?

For me it is the trust in the pictorial that should be freed from everything. Like a composer who hears the sounds in his head before he starts composing, I think myself into the picture. You have to be able to deal with color, form, and dynamics and create something that has a tension, that is interesting, that goes into depth and that perhaps opens a space for those who can perceive this pictoriality in this way – about painting, the world, being human. So when I see works of art that touch me, I know I am connected to something that really has gravitas. And that is also my claim – and my offer to the world.

Are there other artists whose works evoke such a feeling in you and who you find good?

Oh, it’s difficult. There are very many, and I don’t wish to be reserved in answering. Paul Klee is very important for me. When I was a young person, Matisse moved me a lot. I think Nicola Tyson is very good. And Odilon Redon, he is a real poet. Maria Lassnig and Joan Jonas also inspire me a lot. Together with them I would like to do an exhibition.

Is there anything that upsets you, for example misunderstandings about your art?

Yeah, all the time. From the moment people understand that you are a woman, they always want to interpret your work through your gender. Some people think my works look feminine. I don’t know what looks so feminine about it. To be subject to such an assessment drives me crazy, and is why I don't feel like exhibiting work or entering into a discussion somewhere if I think things are likely to go in that direction, terrible!

How do you think your art fits into our time?

I think that I am driven by a fundamental optimism, otherwise I would have abolished myself long ago. I work with these simple materials because I find it very important to counter our wasteful culture with all its technology generated ephemera. In this sense, it is a political decision to use waste. I like the idea that something inspiring can be made from found paper, for example old flyers. It embodies basic values. It pains me how irreverently so much this beautiful planet offers us is treated, and I would like the dimensions despite how extensive it is, to remain on a human scale. I don’t want to overrun anyone, things must still be able to grow. Even in our time, where many artist’s work seems to be in accord with the motto “the bigger, the better”, it is actually the case that more content would often be for the better. With my art I want to refute the soullessness of our time, the excess of materialistic consumption and these matters are of little matter to the art world, which is of course intellectual and politicized and has no need to deal with such questions. I am concerned with sustainability on a number of levels. It shouldn’t be that every biennial should become bigger and more expensive than the previous one, where does that end, and what is the point? It becomes an elitist entertainment machine that I don’t want to be a part of.

Are your paintings, in which you, from a purely technical point of view, open up several levels, also to be understood as new social spaces that you wish to occupy?

I insist at least on the hope, nice that you recognize it. That is the drive. Otherwise I would have to find my way in a triviality. Why else do I have to paint a picture? There are already enough good pictures. A picture must have a range that includes a plane of reflection, otherwise I would be in a vacuum, which is by no means the case; I am really very conscious in this world.

When can you hand over a work, when is it finished?

At some point it is finished sufficiently. But it is never entirely finished. That is simply life. And I think that in the end, such a finished work of art must not stand in front of you in all its commonality and glory, rather it should retain a certain vulnerability in its incompleteness. A painting can sometimes lie on the floor for two years. Such layers and spaces do not develop quickly. That is the problem.

Do you draw much energy for your own artistic work from the contact with your students?

When things go well between us, like with Amoako Boafo, it’s great. Then it is the opposite of this absolute loneliness. Then there is a resonance, a counterpart. That’s the moment when I get goose bumps. Then I know I can believe in this humanity, it’s of no matter whether someone is black, white, or whatever, we are strong together. We don’t allow ourselves to be displayed as marginal figures in history. I find that incredibly important, and that makes me happy as a human being. And that’s why it’s worth doing such a job, it’s worth it for this moment when such a rapport occurs. It is important to me to give people the feeling that it is worthwhile to take each other seriously and to respect each other.

What is your advice to students who attend your seminars?

Many young people come to the academy and wish to have an exhibition immediately. I then say, first paint a picture that we could look at and agree is good enough. One. Many have failed at this. Why should you have an exhibition if you have nothing to offer? This purely career thinking, with which many people put themselves under pressure, is perverse. And it is a symbol of our time. Where is the content? I also tell all of my students repeatedly: the pictures of our time have yet to be painted. They have to think that through. Not to repaint something, but to make it new, not at some point, but now.

"It is the whole world Kirsi, we don't take it any lower", acrylic, ink, paper on paper and canvas, 2020, Photo: Emilia Pennanen

Infinite displacement, 2018-2020, acryl, paper, 255 x 250, Photo: Emilia Pennanen

I, 2020, 280 x 250, acryl, paper, fabric, Photo: Emilia Pennanen

Love Affair, acryl, paper, 2020, 235 x 210, Photo: Emilia Pennanen

Interview: Dr. Sylvia Metz

Photos: Kristin Loschert