Whether as Hamlet, as a serial killer in Tatort or as a human paintbrush in a video by Deichkind, Lars Eidinger, born in 1976 in Berlin, is one of Germany’s most successful film and theater actors. However, for many years Eidinger has also been making art – he photographs and presents himself as an art object in social media. Many of his art actions caused a sensation, for example, when he had himself photographed with a five hundred Euro Aldi bag in front of a homeless encampment. In Vienna, the artist will hold his first gallery exhibition in Austria in 2022. Collectors Agenda has interviewed him – about the philosophy behind his art, pop culture as a source of inspiration, and the importance of acting.

Lars, what is the philosophical background of your art?

Life means movement, stagnation and inactivity, means death. That’s why Hamlet’s last sentence, “The rest is silence,” can also be translated/transposed as “The rest is stillness” and not, as is usually said, “The rest is silence.” Holding on to the moment is utopian and yet inherent in the notion is a great yearning for redemption. The English grammatical term “present perfect tense” explains it even better. Presence describes “being there” in the literal sense of “being present in the moment,” “in the here and now.” Perfection is an unattainable ideal, a state that is not fulfilled in life, is only reached in death. Nevertheless, it is a state for that we inevitably strive for, like a longing for death. Through the omnipresent presence of death, life achieves its appeal and value. In this sense, the term is an oxymoron the contrary nature of which causes friction that releases an energy from which I draw artistically.

Because you posed with a 550 Euro leather bag in the Aldi look in front of a homeless camp you were heavily criticized. How did you come up with that idea?

“Man’s destiny is man,” says Berthold Brecht. This becomes obvious to me. Human history as a dystopia. Sometimes we humans seem to me like the Schildbürger who forget the windows when building a town hall and then try to carry the sunlight in with buckets. Many of my motifs are inexplicable. How do you explain why a homeless man is sleeping in the cold in front of a heated bed store on the street, separated only by the store window.

I am mostly interested in the invisible. That which we commonly conceal, that which is hidden behind the illusion. I want to depict it without moralizing, I don’t want to explain my view of the world, but show it, in visual language.

I am interested in expressing myself by sharing my impressions, to provoke in the original sense of the word, of provocare. The evaluation lies in the eye of the viewer. My art is not about morality.

Photography plays an important role in your oeuvre. How do you select the motifs for your images?

Of course, the selection of the motifs is already a criterion, I can’t free myself from it. But how the motif is commented on, what thoughts and feelings it evokes in the other person, is individual and says more about the viewer than about the photograph itself. I find it interesting that my photographs, are taken all over the world, but universally focused upon cities; and that there are themes that immanently describe and constitute human activity across all cultures. I try to establish these connections and to show the conflicts and contradictions arising from them. However, I see myself as part of this discord and hesitate to distance myself and judge, rather I confront myself as a viewer forcing myself into a position of confrontation.

Lars Eidinger, Salzburg, 2021

Lars Eidinger, Paris, 2020

Lars Eidinger, Brig, 2021

Lars Eidinger, Salzburg - Cleveland, 2021

Lars Eidinger, Paris, 2019

ƎVI⅃ which will take place at ALBA Gallery will be your first exhibition to open in Austria in 2022.The color green will play an important role in many of the works presented there. Why green of all colors?

Viewers don’t actually get to see the Chromakey Green. It is a placeholder for something that will later be replaced. For me, it’s about disillusionment in the Brechtian sense: “Don’t stare so romantically at me!” When the illusion is unmasked it is not about a loss, but an increase in experience. It takes the viewer seriously and tries not to deceive or delude them – disappointment in a positive sense. Through analysis, the observation becomes more sensual and complex.

You take photographs with both your cell phone and an SLR camera, is the use of the latter why you show older photographs you have taken?

It is important to me that older photographs also appear in the exhibition, to show that my view has not changed significantly. It is a fact that I now mainly take pictures with my cell phone and less so with an SLR because of the convenience of the cell phone. I further appreciate that the cell phone serves as an intermediary between me and the subject in a way that a camera does not. When digital cameras were first introduced, I was bothered by the fact that one no longer looked through the viewfinder, but rather through the display. Now, however, I appreciate exactly that distinction since through the viewfinder, as the term suggests, I am able to search for the perspective only after locating the subject, and then have to correct my angle of view.

What makes cell phone and Instagram based social media photography so special for you?

Today, when I hold the cell phone camera between me and the subject it is much more in line with what I’m actually seeing. I also like that the gesture has something of that of Hamlet looking at the court jester’s skull with his arm extended, philosophizing about transience; as a vanitas motif and memento mori.

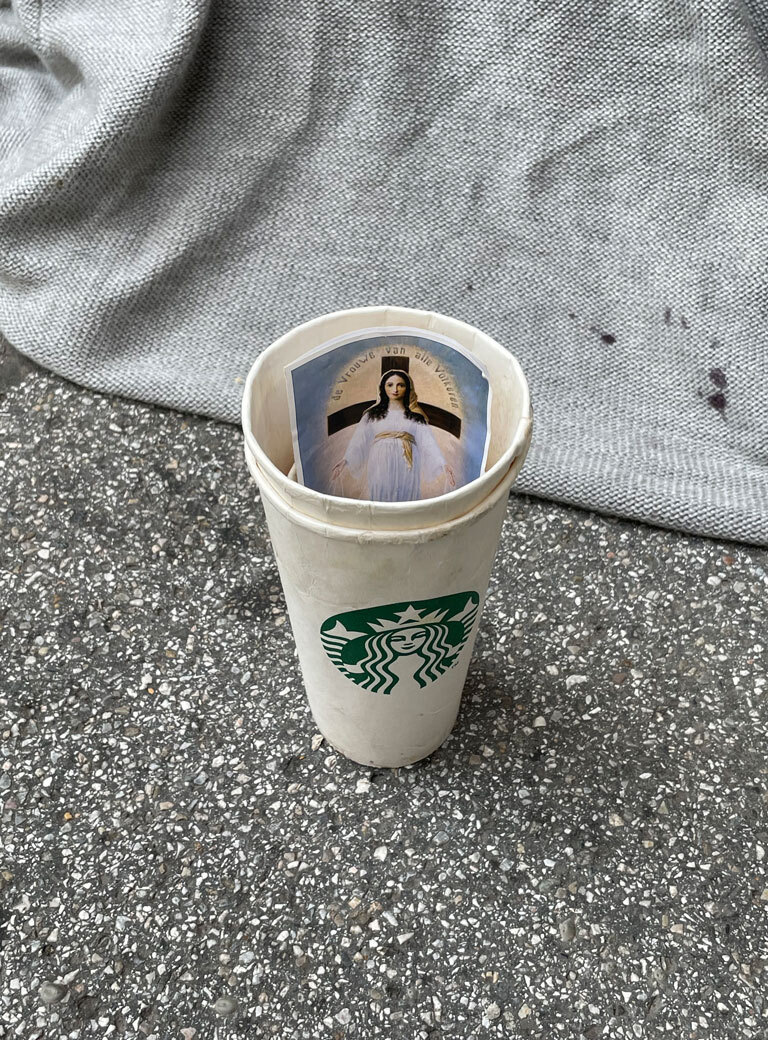

Lars Eidinger, AUTISTIC DISCO

What role does pop culture play in your art?

I grew up and was socialized in the 80s, the heyday of pop culture. Pop is the cult of the perfect surface and the negation of everything subtle and profound. I realized for myself that it makes me unhappy because it makes me believe in a world that does not exist. It is like an instrument of capitalism because it promises happiness and awakens desires that we think we can satisfy with consumption. That’s why the drug is the most apt symbol. It becomes an end in itself. The goal is no longer the experience but the satisfaction of the addiction, the longing for it. Longing as a state. That’s what I tell about in my paintings.

How do other artists perceive you?

“Lars Eidinger is his own opposite,” one of my favorite artists, John Bock from Berlin, once said.

In the video The Creation of Lars by Deichkind, you were involved in the creation of a two-hundred-square-meter painting – as a human paintbrush. How did that feel for you?

I’ve always been a big Deichkind fan. In 2007, I quoted them in our Hamlet production at the Berliner Schaubühne. They have always been a source of inspiration and reference for me. In the meantime, I have participated in four of their music videos. The idea of using myself as a human paintbrush didn’t seem feasible to me at first. But the realization of almost utopian projects is one of the great talents of the artist collective. That is what makes them so visionary. Similar to the shooting of the video No Party, which we shot in just one day working on The Creation of Lars was physically very demanding. We had underestimated what it meant to be dragged across a screen with a body weight of 90 kilos. It had the effect of sliding over synthetic turf while playing soccer. I was covered with abrasions all over my body. We also shot this video on one day into the wee morning hours.

Erschaffung Lars, Video still from the DEICHKIND intro film 2020, directed by Timo Schierhorn and UWE (Auge Altona). (c) Björn Beneditz, Henning Besser, Christian Rothmaler

Lars Eidinger (c) Nils Müller

Besides art, you are also one of the most sought-after actors. What does acting mean to you?

The longer I practice the profession, the more I actually want to get out of the creative moment, because I no longer believe in that. There is actually something backwards about it, if I think about how I am going to do something beforehand and then implement it, then it doesn’t have the validity at that moment that it could experience, because it’s something from the past that lays claim to the future. For me, that’s also the reason why I am not so attached to theater, because theater, in contrast to film, celebrates and cultivates transience and finitude, and film, as the vocabulary already states, you say “the scene has died,” it tries to hold on to something, which basically contradicts life. Theater means letting go, and I believe in that, that’s the beauty of it. When I give someone a bouquet of cut flowers, the eroticism is in the morbid charm that these flowers have already passed away. A potted plant, on the other hand, lacks that eroticism.

In the last Tatort Borowski and the Good Man, in which you participated, you played the sinister serial killer Kai Korthals. Do you like playing bad guys?

At drama school, I was told that I would never play villains because I had too nice and sympathetic an aura. That annoyed me so much that I worked out “Franz Moor” from Schiller’s Die Räuber as an elective role for my final audition. I wanted to understand what makes a character seem evil. Is it really his phenotype or his charisma, or is it rather a certain abysmal absence of scruples in his thinking? In retrospect, I find it interesting that these days I am associated with just such a role.

You once said that you don’t like people that much. What did you mean by that? Does that also apply to your artistic work?

I can come to terms with my image and to a large extent I can understand where it comes from, but interestingly enough I would say that the opposite of how I am perceived by the public is the case. So someone like me, who is laden with complexities, is also shy and reserved, in trying to compensate for all of that with a certain expenditure of energy, inevitably appears as rather arrogant and self-confident. In fact, I would describe myself as anything but self-confident, simply because someone who is truly self-confident can draw this awareness from himself. I on the other hand, become aware of myself in the reflection, that is, in the counterpart, and that is why I need the public. There is a poem by Thomas Brasch that describes this very aptly: “My profession means not hiding myself, but discovering myself publicly, finding myself by losing myself, not preserving myself for myself. I want to find myself since I live.” That is how I understand my profession.

Lars Eidinger (c) Nils Müller

Interview: Kevin Hanscke

Photos: Nils Müller