Although Liliane Lijn might best be known for her “kinetic art”, her artistic scope goes far beyond movement. Since the 1960s, Lijn has pioneered a new way of working with a multitude of materials, from plastics to minerals, exploring the intersection between language and image. Her continued exploration of the cone, or koan, forms a revolving centrepiece in her long and eclectic career through small-scale pieces and large public works. Lijn’s art has never been defined to one medium or place, spanning time and space across everything from film to live performance. Her studio continues to be filled with experimental pieces pushing the boundaries of form and genre.

Liliane, where did your interest in the koan come from?

It is a ubiquitous form, and I think very early on I became interested in the triangle and the circle. It took me a while but I then realised that they’re both exactly the same. A triangle in three dimensions becomes a cone, but it could become something else, you could make a pyramid. Then if you think about a cone, it is really just lots of layers of circles. I was interested in geometry and how it interacted with light and language. So somehow these things all came together quite early on. At my first show in Paris in 1963, I showed works that were light works and this one piece, which was a sort of double cylinder. I didn’t have any conical pieces at that point, but these cylinders had parallel lines on it, so when both were in motion at a certain point, you had interference. So you might see a bit of colour, and certainly vibration.

When did you start making the koans and what inspired you to do so?

I think in 1965 or 1966, and the first ones I made were striped. Red and white, yellow and white. Very related to signals, the road and the idea of the road as a place of adventure and unknown. I read Robert Graves’ books about the Greek myths, and the notes were the most interesting part because his thesis is that these myths were the battle between the patriarchy and the matriarchy. I read one story about a white ash cone, in Graves’s The White Goddess, in which the white goddess was the conical mound, so that was like a confirmation for me. That was when the koan became the perfect vehicle for everything I wanted to explore. All the orbital paths of planets are elliptical, and then in physics there’s the cone of light. All of these things put together made me feel that I was onto something.

Does the koan have a persona for you?

For me it was female. There was no doubt about that. I had people say it was phallic, but it’s not. Turn it upside down and it’s yonic. It’s a skirt. And as years went by, I heard more and more stories about cones. Like the aurora borealis is created by solar particles falling into what they call ‘the lost cone’, which is at the pole, both poles. There’s a conical area where there’s no magnetic field so the solar particles can fall into the lost cone.

What materials did you use?

Some of them are made of clay, others out of wood or cork. I’ve always spun them. The cone is spinning, and my hand is still. I then went beyond the spectrum, the spectrum of light and then I realised I had to put black lines in it. It creates a language.

Where did your love of words and language come from?

My family. My parents and grandparents were not American, and everyone spoke different languages. My mother spoke Polish with her mother, but my father couldn’t speak Polish and he spoke Russian with his mother-in-law, Yiddish with his father. My parents together spoke German, and my uncle spoke French. And from all of them came a lot of stories. My father was a great storyteller, and my mother was pretty good too. He made them up, and when they were true you never knew if they were or not. I wanted to be a writer when I was a child, I wanted to be a journalist when I was twelve. But then, when I was fourteen, I left America and continued my studies in Italian.

How did that develop into the ‘Poem Machines’?

That came out of working with lines. I thought that words are made of letters which are lines so it seemed logical to me. When I did the first one which was just the alphabet, I had a friend who was a poet and she wanted me to use her poems, then other people came and wanted me to use their poems. The problem was I couldn’t use their poems as they were written. I had to cut them up because they had to fit on to the form, which at that point was cylindrical. Later on, in the 2000s, I made them much more complex. There are three layers, three cylinders nested one inside the other and each is like a page.

Did that come from André Breton and automatic writing?

Very early on I was inspired by Breton and I had an interest in automatic writing, although more automatic drawing. But these are more to do with visuals, I’m really interested in perception. Each one is quite different, and your brain will actually change the focus length by itself, so you read it without trying to read it. I’ve always been interested in disrupting syntax, because I love grammar. Then you start reading it in a different way. I made a really large one for Leeds University which is nine metres high, and two metres in diameter. I decided I wanted to collaborate with the students, so I invited them to send me a few lines, and I cut them up and created a poem.

What is the experience of creating a larger public work like that compared to the smaller pieces?

Normally I don’t design anything for any space, I just work on something. But if somebody comes to me and asks me to make a work for a definite space, then I have to work within the confines of that space. I don’t like making public art anymore. When I was starting it was a great opportunity to create something large, on a different scale. The trouble is that usually the budgets are small, everyone is pushed to work for nothing. And things change, so I had a piece which someone wanted to give back to me because they sold the premises. It’s totally dismissive of the artist. The first public work I made was White Koan for the University of Warwick, and I’m lucky that they have it and they love it. The students love it, and the vice chancellor wanted to throw it away because they couldn’t restore it and the students went on strike. This can happen, it becomes a part of a place and a part of life.

You have filmed your works and worked with filmmakers. How did you develop that interest?

I’ve had an interest in film for a long time. I think the first film I was going to make was about a trip from Nottingham to London in a train, just looking out the window at the telephone wires and how the distance between them changes as the train moves. That movement fascinated me. I’d already made koans with oscillating lines, so it was connected to that work. But when we had the footage to make it, I was invested in making this big sculpture, 20 feet high, for Plymouth. I wanted to film that in the factory because seeing it in parts, elliptical bits of steel, was really interesting. That didn’t work out, but we filmed the koan I had made and I had all this 16mm footage to cut, and I’d never edited before. I found a friend who had a film studio and she showed me how to edit my film. So I cut it myself and really enjoyed it. That film is called What is the Sound of One Hand Clapping?, which is the most popular film I have made.

How do you feel about the label of “kinetic art”?

I wasn’t at all interested in kinetics. I was interested in light, reflections, and shadows. But it’s full of childish pleasures, which is why it is so popular. Kinetic art has always been very high on the popular list and very low on the critical list. It’s never taken seriously, but if you have a big show of kinetic art it pulls a lot of people in. Because people, like animals, are fascinated by motion because it is a basic prey-predator thing. It’s all a kind of play.

Did you feel like you were creating a different form of art?

Yes. I was in New York and everything was Pop Art. I’d show pieces to a dealer and he said, “Oh, it just looks like Pollock.” How could it? But he didn’t care. It felt like I was exploring an area that I didn’t know anybody else was. I wasn’t living with Takis, my first husband, at that time but he was doing something that was quite unusual, working with magnetism and an invisible field of energy. He was fifteen years older than me.

What kind of sculpture are you working on today?

I started working on this current piece around 1990, but I couldn’t work out how to make the wings. I have the original model here, but the finished work will be about three metres tall. What I worked out to use is mica, which is a natural stone. I’m just trying to figure out the base, and I’m working with Stephen Weiss, my husband, who’s more technical than I am! He had a mica factory, so that’s how I started with the material. I used to go to the factory and discovered that it’s fantastic stuff, a kind of old technology.

Do you continue to work with other mediums?

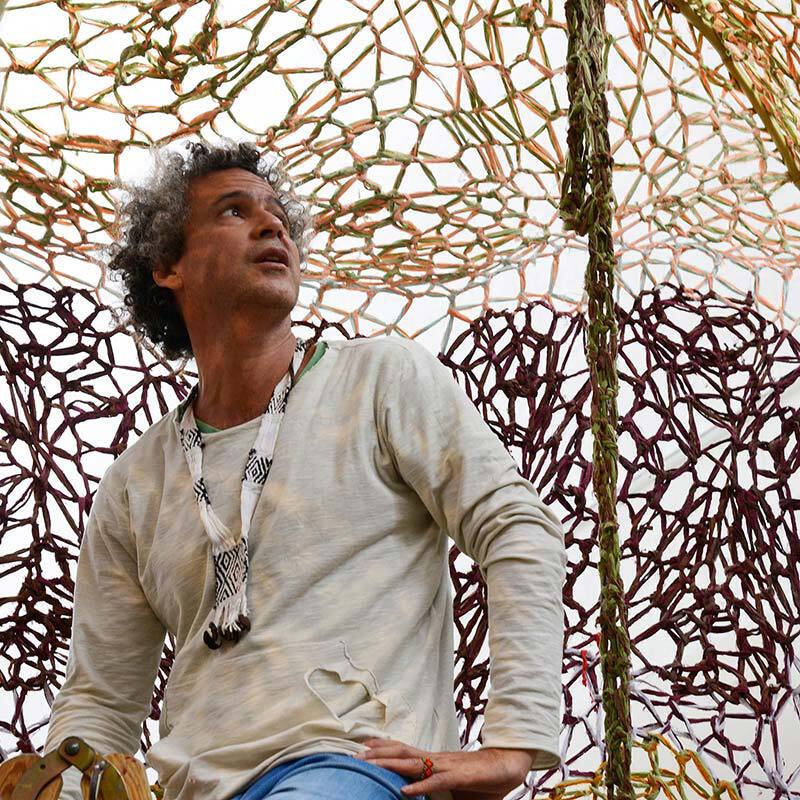

Yes, for example I am working on this piece with a Korean performance artist, Yong Min Cho. It is a costume for moving through and transforming into Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth. It was an insane idea to make it out of paper, because I had made a couple of what I call “dresses”, which were made out of plastic bags for him. I tied all these bags to the piece at the neck, it becomes like a cloud, and they make this wonderful sound when he moves. I did not realise with this one how work intensive it would be. But it will be incredible when Yong Min wears it, because he can transform it from a flower to a creature, to the goddess, and then a kind of monster.

The survey exhibition of your works, Arise Alive, opens at Mumok on 15 November. How involved do you like to be in the curation of your works?

Of course I like to be involved. It’s difficult, and Mumok is difficult as a layout. It’s this great big, enormous space. It’s square, and very high. So we have to make spaces, and that’s what Manuela Ammer the curator is doing. I am putting the finishing touches to my memoir, I’m trying to do everything at the same time. But I have to give very detailed instructions for the display of the works, and people don’t always follow them. With the exhibition at Haus der Kunst in Munich, I had this idea that you start in light and end up in pitch darkness, so you start with things that can be shown in the light, in the middle it’s grey, and then spotlight pieces in the dark at the end. There’s two big sound installations that need to be seen in complete darkness, and it was difficult because they were close and sound migrates. It’s always exciting to see it come together, and how the works interact in new ways and new spaces.

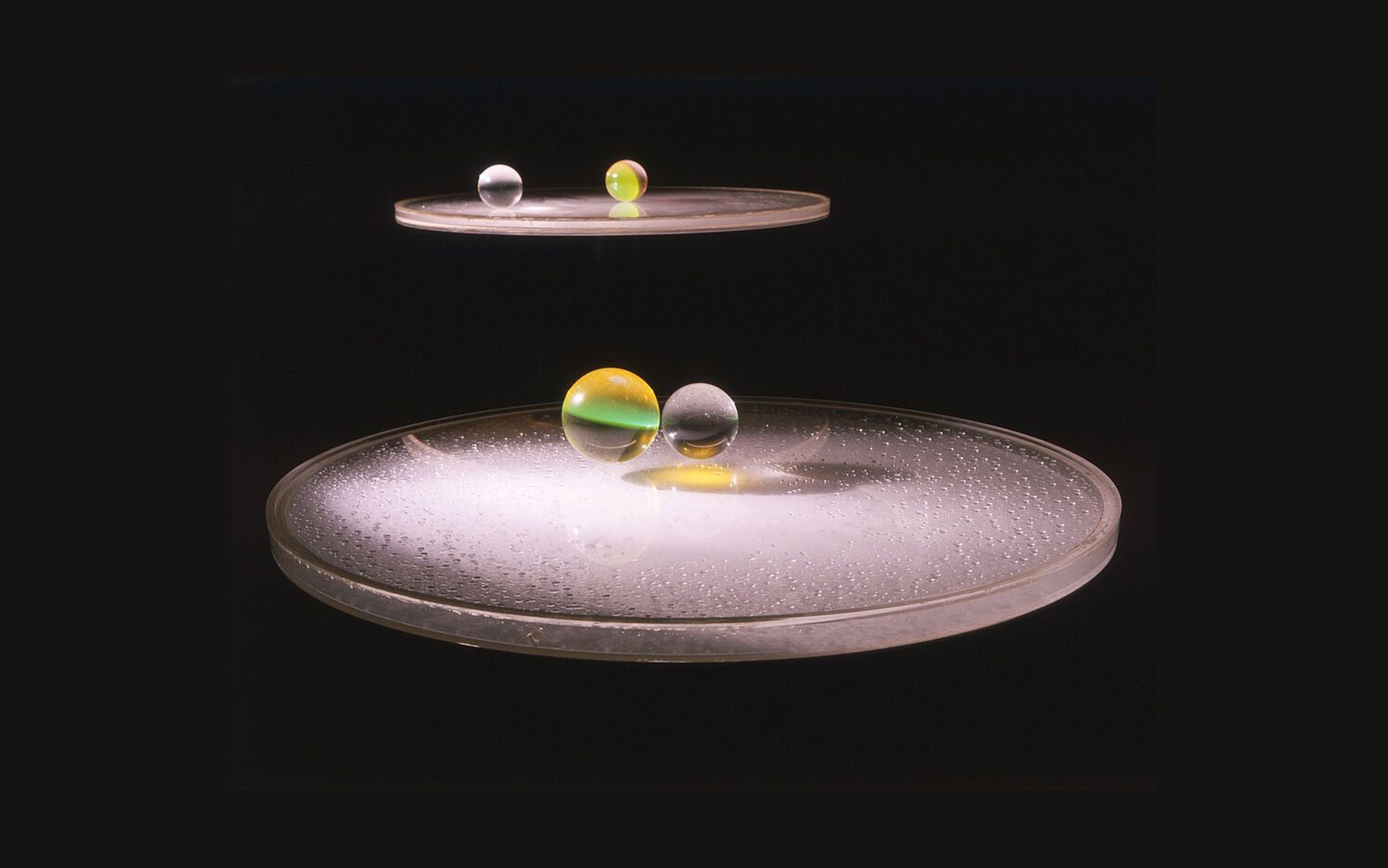

Liliane Lijn, Liquid Reflections/ Series 2 (32"), 1968, Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Rodeo, London / Piraeus, Photo: Stephen Weiss © Bildrecht, Wien 2023

Liliane Lijn, Conjunction of Opposites: Lady of the Wild Things and Woman of War, 1986, Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Rodeo, London / Piraeus, Photo: Thierry Bal © Bildrecht, Wien 2023

Liliane Lijn, Get Rid of Government Time, 1962, Courtesy Liliane Lijn and Rodeo, London / Piraeus, Photo: Richard Wilding © Bildrecht, Wien 2023

Interview: Lillian Crawford

Photos: Liz Seabrook