Austrian artist Lisa Holzer is busy with desire. By enforcing relationships among food, digestion, emotions and body, she explores what lies underneath today's increasingly glossy and easily consumable surfaces.

Lisa, you were born in Vienna and lived there until you were thirty-six. Is it difficult for as an Austrian to live in Berlin?

No, not at all! I don’t think so. It was exciting for me to come here. Vienna is really quite a bit smaller than Berlin. I was born and raised in Vienna, at some point however, Vienna seemed too narrow, also I wasn’t interested in working only in Vienna and to be only known locally.

How is Berlin different?

In my opinion, Berlin is much more international. Berlin is a bigger challenge. It is much more difficult here because there are so many good people, artists as well as galleries. It is much harder and therefore much more realistic here. In Berlin there is little money and nobody is waiting for you. Other artists are not exactly interested in you, nor is it easy to meet people.

And yet you obviously seem to feel comfortable there?

Even if a lot of things are difficult, it is a challenge and that is good. At least, it has been very good for me – both for my work and personally! In addition to that, one can still live very well and reasonably in Berlin. One can have children, which for an artist is much more difficult in other metropolises.

Do you still visit Vienna often?

I love to be in Vienna, I enjoy visiting friends there and the food is wonderful. But I am also glad to leave after a while. I think it is important to keep a certain distance from the city one comes from. What I really miss are the coffee houses. Not that I have been visiting coffee houses a lot in the last couple of years, but I miss the opportunity. The Viennese coffee houses are very special.

How did art start for you?

Both early and late. My parents were very interested in art. I virtually grew up in contemporary art museums. After my high school examination, I attended the college for photography at the Graphische [Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt]. The focus there was not on art but rather on the technique of photography. When I was twenty, I would have liked to have studied at the Academy [Academy of Fine Arts Vienna] or the Applied [University of Applied Arts Vienna], if they had offered photography classes. Unfortunately, they didn’t. At the time, I would not have dared to apply for sculpture or painting classes with a photography portfolio – I think it is possible now. But I was afraid of admission exams anyway.

How did it begin?

I began doing photography jobs, I worked for Falter and in the evening I studied at the School for Artistic Photography with Friedl Kubelka, but only for one year and once a week in the evening, which can’t be compared to an art study. Actually, I haven’t really studied art. A career was not what I was interested in at the time. I’ve done my photo-jobs, worked as a waitress and I took some psychology courses.

So you weren’t really focused?

Not in the beginning, but at one point it made me crazy to photograph only for other people. I wanted to do my own thing. So I had to decide to either study and make art or to try to get exciting photo-jobs. I understood that I had to decide between one or the other, art or good photo-jobs. I simply didn’t have enough energy to do both. It is difficult enough to do one thing well. I wanted to make art, but in my late twenties I did not want to study at the Academy with all the younger students. I also did not know which professor to choose. The only thing I knew was that I had to find out what was "mine" regardless of whether I studied or not.

How did you find out what was "yours"?

I realized that it was easier for me to find out by myself what is important to me. I don’t really function well in groups. Friends of mine had a big studio, and I moved in with them and continued to do my photo-jobs. These were commissions that I didn’t have to think about much: darkroom jobs, prints and contact sheets for others and such things. At the same time, I tried to do my own work, to invest all my energy into art without really knowing what that really was for me. It took me a long time to find out what kind of art I wanted to do.

How did you find a personal access to art?

At the time there existed the Depot in Vienna, where I copied the Texte zur Kunst [Texts on Art]. In the 1990s, Texte zur Kunst was quite good. This was my art study. For me this slow approach and finding out by myself was the best I could have done, even if I was missing out on contacts which are normally made during an art study. I didn’t know artists or gallery owners. At one point I started to go to openings where I met people.

Did you have something like a portfolio, to show people?

The good thing was that the BMUKK (Federal Ministry for Art and Culture) regularly awarded scholarships, which meant that three to four times a year one had a reason to create a portfolio, to create works despite not having an exhibition at which to show them. It was good because it actually gave me an incentive to produce work. And at one point my career began to take off with self-organized exhibitions and group shows.

“I can’t do 'ugly'. I’m still working on that. To make something really ugly would be very interesting. I mean something really ugly.”

With photography you have learned a real trade.

Yes, although the technical side has never really interested me, but I can do it. I have photographed since I was fourteen, I have always run around with a camera. What I have really learned is seeing. That is perhaps the most important element in photography and for making pictures in general. I certainly know how to take a good photograph, but I think that is not so important. Sometimes it is better that one doesn’t know how to do it and to make and accept mistakes, the result is often more exciting.

In your work you also use found objects and don’t always photograph everything yourself.

You’re probably referring to the series Passing under… which contains some photographs that I did not take. These were pictures taken from the Internet combined with my own photographs. Two years ago, I bought a new camera. Since then I photograph much more.

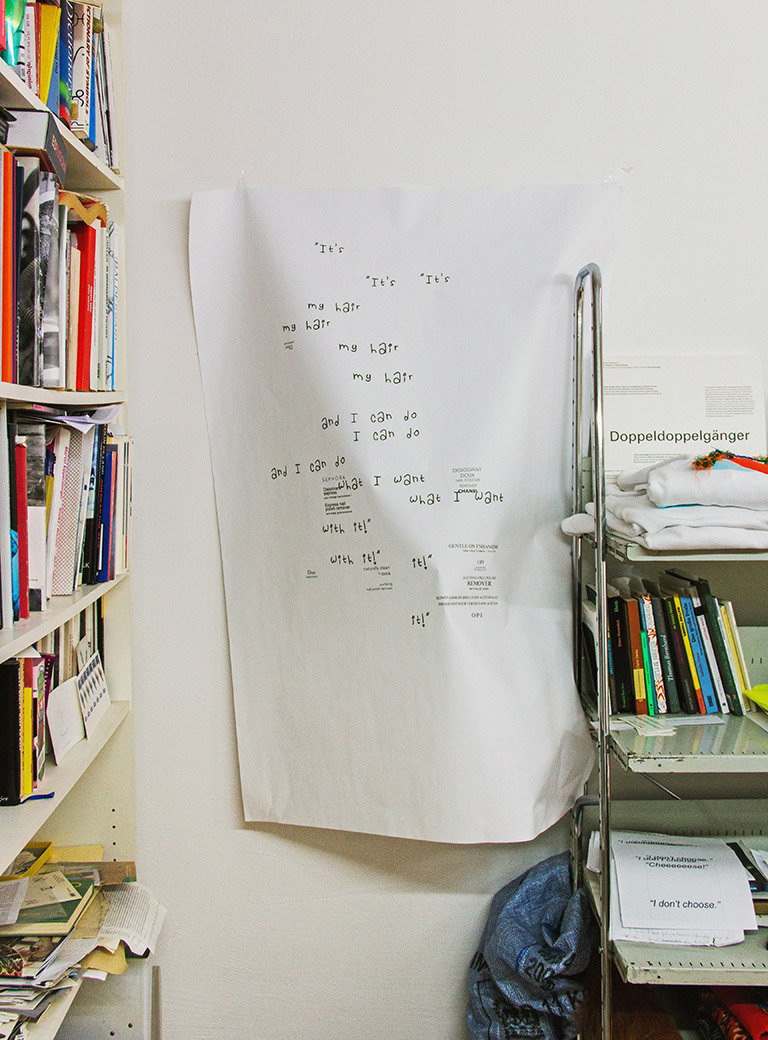

It is noteworthy that text plays a big role in your work.

Text is very important to me and writing texts has been part of my practice for a long time. Some pictures consist only of text. I love press releases. I am always writing them myself. In regard to press releases I like my own work. However, there are many people who are not at all interested in press releases and don’t read them. In my last works such press texts appear even in the pictures. It was important to me to show that one can’t have pictures without text.

Are you saying that your texts serve as picture captions, as kind of picture explanations?

In principle the texts are notes to myself about the work, often a kind of dialog with myself. With the “you” in the texts I speak to myself, the viewer can also feel addressed, but they are actually written for me.

Where does one learn to talk to oneself?

It began with the applications for the BMUKK. One had to write about one’s own work. I liked to do it and considered it strange that someone else would do it. I began writing press releases for my own work and to give the works titles. This often led to ideas for new works, from these texts came new ideas for pictures and vice versa. The process influenced both and that is what I really like. Sometimes it was a sentence that resulted in an entire series. Passing under... for example is a sentence by J. Lacan, where an Hommelette (a form of objet petite, the object origin of desire) was ultra-flat in order to pass under doors, which I found super. It became an entire series.

What is it that fascinates you in regard to text?

My texts are yet another possibility to communicate the same idea. They’re part of my work. On one hand I show pictures and on the other hand I have to say something about them. That is yet another level. Often the texts are very personal. Another reason why text is so important to me is that I can neither draw nor paint. One can do everything with text. One can draw with it, one can think about something, one can claim anything. I find that super. That is much more difficult with photographs, even if I try. It is also a good opportunity to include humor, and it is fun to write.

Do you mount and process your works, or are they classical photographs?

Sometimes, however, the works that can presently be seen at the Lira Gallery in Rome and the works for New York have been classically photographed: An object is being placed on a background, lighting is set and the object is photographed. The text is added afterwards and sometimes the colors are changed.

What role does aesthetics play in your works?

Beauty is important to me. I would like to make something attractive, but at the same time its content can be very vicious. I can’t do “ugly”. I’m still working on that. In the beginning it was the same with text. I couldn’t really write. But it's a craft that can be learned and acquired through training. The more you write the easier it gets. It was a real challenge. But to make something really ugly would be very interesting. I mean something really ugly.

Your works look more cheerful than their content really is?

Yes, one could say so! I believe nowadays one cannot make art without joking about the fact that one makes art. There are no longer taboos. One can do anything. For example make very elegant photographs of pig ears and at the same time to keep up the freedom of art and take very seriously what one creates does not have to make sense, doesn’t need justification. I would like to underline this and communicate a certain kind of humor or a certain kind of associative thinking or sensibility.

Would you call your works “political”?

No, not really. I would like to explore things that interest me, that are personal, where you feel something. Art that I like has to do something with the time in which we live. It does not have to be the direct presence, but things that move us today. It can also be quite old-fashioned. If one is somehow sensitive, then it is completely impossible to do something that has nothing to do with what happens. I prefer when it is not catchy, but when one senses it rather subtly. If one is sensitive and somehow one has to be while making art it happens regardless. One can’t do anything that does not reflect the environment, even if one wants to do so. it. I find it difficult when artists claim that they’re doing political art.

In your opinion is that what a contemporary artist has to fulfill today?

No, as an artist you don’t have to fulfill anything!

The profession of the artist is not a classic “nine-to-five-job.” Do you sometimes have time to be private? Do very private situations where art no longer plays a role exist for you?

One simply has to take time-out. Having a child is very helpful for having no art on your mind. Picking up my child from nursery school is foremost about for example dressing warm in winter, taking off everything one put on in the morning and not leaving anything behind – it is about very simple practical things. One has quite a different role and task! A child is a real pleasure! My son makes me forget art completely. However, unfortunately I don’t always succeed even if I plan it. When I have a lot to do, I am there physically but my mind is somewhere else. It certainly happens to me, too. But up until now I was fortunate enough not to have to work so long on one piece to the extent that it would become a problem.

But what if more intensive “production phases” were to come? Principally, this would be a positive thing for you.

I don’t know how I would manage with the family if I had a lot of work for a longer period of time. That could become difficult. I have observed it with other people who are very successful with their work that both their art and their children have suffered at times. One has to watch it, but one also has to have a bit of luck, I believe. So far I have managed pretty well. For example, when I am in New York my parents come and take care of my son. The good thing about Berlin is that one can afford childcare. It is important for me to know that my child is in good hands and that in the meantime I can work with full concentration.

Do you work every day on your photographs?

Yes, I actually do. Although I try increasingly more not to work on weekends, it doesn’t always work out. If I am really stuck in my work, I force myself not to do anything for one or two days. Afterwards it gets better. It becomes difficult, when I don’t have energy. I go nuts when I don’t have energy!

Your living space is at the same time your workspace. What do you like about living and working in one place?

It is practical if everything is in one place. I have a workspace, I don’t need a studio of my own. When the sun shines, a beautiful light develops in my place. I like to photograph here at the table or in the bathroom, where it is very bright. Sometimes it gets a bit cramped though, like right now with the work for New York and before that for Rome, when twenty-one pictures stood in the room. Then my son is not so happy because he can’t play ball all over the place.

How is it for a child when the mother makes art?

I don’t think it is very different from other children. The term “work” is something very abstract for children. To make art for him simply means to work. The other day, he wrapped a piece of Styrofoam in blister foil and said that he’s made art. He knows my work mostly wrapped. I thought that was super!

You say of yourself that you can’t paint. However, your work is very painterly.

Painting per se is very important to me. I would almost say that I come from painting, I have grown up with abstract painting. But drawing and painting are not really my thing. I can’t really do it, but I like when photography becomes painterly. The asparagus pictures for New York for example, remind me very much of Gerhard Richter’s candle painting, the one on the Sonic Youth album cover. It has a similar emotion, generates the same atmosphere. I had very bad light in November and used the flash, something I would normally not use. Because the asparagus was boiled and still wet, the result was very painterly through the reflection.

We are standing in front of many packed pictures. Your exhibition in New York begins shortly?

Yes, these are all new works. They’ll be picked up tomorrow morning and shipped to New York. Beginning at the end of February, they’ll be shown in the exhibition Be a Funny Mom at Hester Gallery. I show images of pig ears and these asparagus pictures. Alex Ross, who had invited me one and a half years ago to a group show in London, manages the gallery. I was in New York during the "New Museum affair" and met him there. Afterwards, he invited me to show in his gallery.

You mention the “New Museum affair” rather casually. No false modesty! Last year you participated in the New Museum Triennale. A great honor! How did that happen?

The artist Lisa Oppenheim, whom I didn’t know at the time, had recommended me to the curator. It has happened quite often, that curators visited me in response to a recommendation by other artists. For example Alex Gartenfeld of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami visited me, because Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff had recommended me. To be recommended by colleagues is actually the most beautiful thing that can happen to you.

In “Men what a Humble Word” at Lira you show a series of Pictures of Men and at Hester you show Pig Ears?

Yes, these dog goodies –- dried pig ears. They are available in brown and in white, when they’re called Honey Ears. I know it’s a bit coarse. A year ago I read Houellebecq’s book Submission, which I found excellent. For an exhibition last May, I wanted to make works with finger paint on glass, more painterly and pastose than previous works. Therefore I reviewed an exhibition catalog by Jean Fautrier, a French painter of the 1940s, who painted a large number of paintings with a high degree of pastosity. The catalog contained many works that have to do with WWII. In the process, I discovered titles in his work, which I consider quite appropriate for my new works. However, I dropped the idea with thickly applied finger paint with a heavy impasto on glass because I really could not do it. But I have adopted the titles for my works. The first “pictures of men” came into being.

Why of all things a “Male Series”? Is it actually a series about men, or is it an homage to men?

I found it very interesting to focus on images of men, for in everything that is happening right now in regard to the wars and to terrorism, men are involved on all sides. It is difficult to understand which goals they pursue. For me, the series is about helplessness, their helplessness I assume, and my helplessness in the face of theirs. In the process of my research I have read texts by Klaus Theweleit and found the sentence: “Soldiers are treated like dogs,” which is surely true. And I’ve always thought “old men look like dogs.” Looking at the pictures of men and pondering these two sentences I arrived at dogs and thought, these men/dogs should get some "goodies". I went to a pet shop and besides brown pig ears I found these white honey ears. I had not noticed them before and thought they were really beautiful. Long ago, I used to have a dog, which had loved pig ears. I know it’s quite vicious but at the same time the pictures are beautiful, I think.

On the glass and frames of this series there are transparent drops. What do they mean?

The pictures sweat, and in the case of the Pig Ear pictures it could also be saliva. I have always considered my pictures as being protagonists that could have all kind of conditions. For example, there are works that blush. The inspiration for the glass came some time ago when I saw a work by Florian Pumhösl, which I liked, and in which he worked with behind-glass-paint. I liked it a lot. As the name indicates, it is behind the glass, but that was too strenuous for my works. I would have had to pick up the glass from the framer, process it, and bring it back to the framer – I am just not "nerdy" enough for such actions. But then I started making works with behind-glass-paint on the glass with the idea that the paint on the prints would partially ooze out of the picture through the glass. In the process I arrived at polyurethane and sweat.

The pictures then do secrete sweat?

I like that something oozes out of the picture. Therefore, I have put "sweat" or paint onto the glass of the frames. The material I use is one of the few polyurethane varieties that doesn’t yellow. Its special feature is that it remains as clear as when it is first applied. I apply it to the picture with a toothpick. It is a lot of fun to do that. Depending on how the light falls the sweat can be seen on the pictures or it may be almost invisible. I sometimes extract things from the pictures by producing them again, thus I revert time. I make something that already exists in the pictures. For the opening in New York I’ll do a performance, in which I will bake lobster chips that resemble the honey ears in my pictures.

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer, courtesy of Hester Gallery, New York and Galerie Emanuel Layr, Vienna