The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

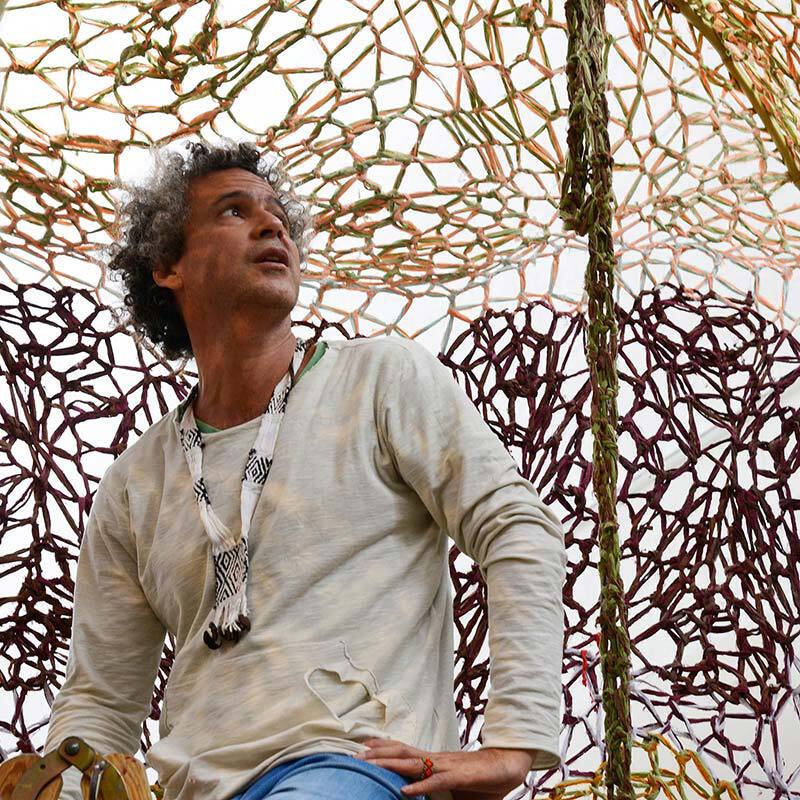

Since graduating from art school in her native Sweden, Liva Isakson Lundin has quickly risen to become one of the most distinguished and distinctive artists of her generation. Recently her sculptural and installation practice has begun to take on an awe-inspiring form and scale, in which her role as artist appears to become akin to that of a technical engineer, and while it may therefore be presumed that she has a background in natural and technical sciences, she speaks in our interview about how in the studio, her art is entirely prompted by trial and error. Known for the juxtaposition of industrial materials and organic shapes, she speaks too about what draws her in making her art toward certain materials. The key is: Resistance.

What road led you into art?

I had already begun to study art in high school and have since then only studied and made art. For as long as I can remember, art has always been there for me in one way or another; I was always drawing or building things. Both of my parents are active in the cultural sphere and I think exposure to the arts and culture, theatre and music in my case, had much to do with it. My parents also had friends who were artists, so the notion of making art always appeared a normal thing to do.

Can you remember your very first artwork? The first work thing you made that you attributed to yourself as a work of art?

I was thinking about that and remembered this one time in high school during a project when I was pushing a fridge from the staff room around, in order to make a chandelier inside it with ice cubes. I think that was the first time I was working in a large-scale fashion of thinking broader than just drawing which I had been doing a lot before then. That was perhaps the first time I thought along the lines of a project informing various bits and parts that needed to be executed to create a whole. Thinking about how to install and how to best present to an audience and so on.

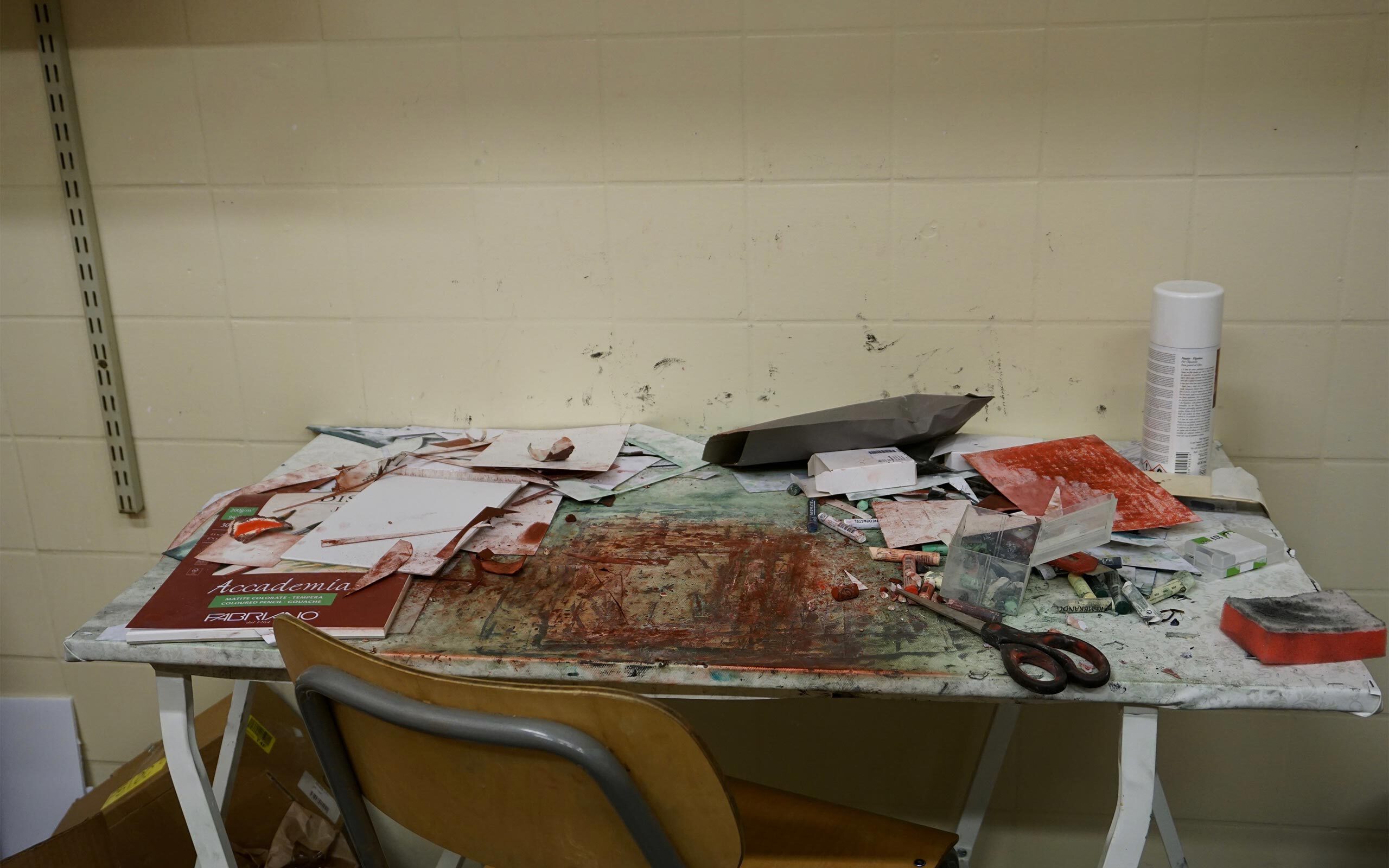

This is a lovely studio we are in, in the area of Gubbängen in Stockholm. There is something of a nostalgic air about it. What are some of the considerations that go into a studio setting and space for you?

It’s a former commercial shop space that a few of us are sharing together. I’ve been here since early this past summer and I’m really enjoying it. It has high ceilings which means you can elevate and mount things in the air. It’s not so precious in the sense that you can utilize it without excessive caution. If you spill something, you spill something. No need to overthink when it comes to the risk of damage. For me it’s important that a studio allows me to be spontaneous and free in my various trials.

For a while you were working in your home and given the scale you work in, that must have been quite a challenge?

In a way that was practical as well, although more congested in terms of space as I was using a bedroom as a studio. But as I was working part-time it allowed me to be time-efficient, and easily transitioning from workspace to living space. However, it required a lot of thought regarding logistics, just to simply build a model and to try an installation out. Today I can have a permanent work space in the studio just for drawing, whereas before it was a question of bringing things out, then storing them away after use.

Looking around in your studio, it is immediately apparent that there are a lot of technical considerations going on here, it would seem that you experiment with gravitational and other forces. Your work has often appeared to inform technical and physical engineering; where does this sense or interest in technical sciences stem from?

I have no technical training or background at all, I try my way forward instinctively and I improvise a good deal. I also find it fun and exciting in terms of problem solving and figuring out “equations” that relate to the use of certain materials. Building things require a need for technical solutions and are a part of my trial-based process.

How much technical support do you need outside of the studio?

As far as exhibitions are concerned, I will mostly have worked to the best of my abilities to make things work, for example, trying out the means by which to suspend an installation in the air. As I’ve begun undertaking commissions for public site-specific and large-scale installations, safety prerequisites and cautionary measures are a necessary consideration and require the need to consult experts.

Interior architecture seems to play a big role in your art. What is its significance for you when making and presenting art?

To begin with; the room, walls and floors are often used to “support” a work. The work is often site-specific and reliant on the room in order to “exist” and is given “permanence” once it is moved into and positioned in a space. In the studio you could say I practice on how to do an installation more than making a complete work.

Are there any repeatedly occurring misperceptions about your work that you would wish to clarify?

Not exactly. I mostly enjoy hearing how people perceive and relate to my work and don’t mind learning that someone has vastly different thoughts than I do about it. I find it difficult to say that someone’s perception is “wrong”, I see it as presenting something that gives rise to a “dialogue” between the work and the viewer and what direction that takes is beyond both my control and judgement. It’s flattering that people engage with your work and try to address it in words. It’s quite another matter of course, when something is written about my work, which gives the impression of expressing my viewpoint when that is not the case. Personally, I have to say, that I don’t find speaking about and analyzing my work the easiest of things.

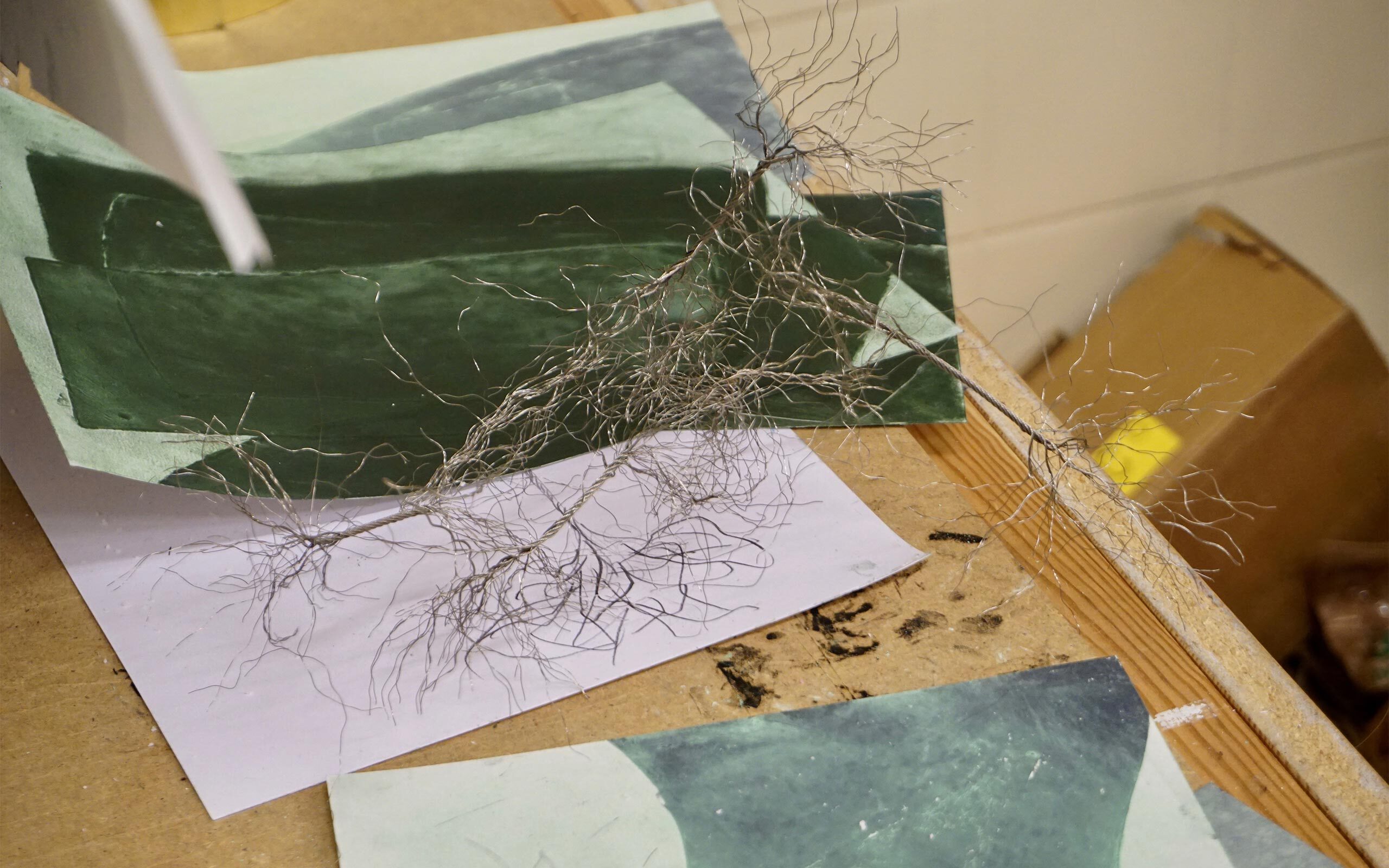

You work often with juxtapositions between just a few materials that are joined together, e.g. latex and metal or glass and silicone. What draws your attention to a material?

Well it needs to be challenging; there must be some resistance towards me, and the material should in a way possess a will of its own. What’s complicated about them also tends to be their strength in my eyes. Take latex; it’s very elastic but also very fragile. Spring steel is super resilient and malleable. You can do what you want with it but then you also need to keep in mind that it is sharp and potentially dangerous and can turn back on you. The weight of the material is another important factor that must be taken into consideration.

Are there materials that so far, and for whatever reason have not been “a fit” for you?

You should never say never. But clay has been tricky. I love working with it, but I think it hasn’t quite fallen into place yet.

I feel compelled to ask you; do you see your works as metaphors for something?

I wouldn’t say they are metaphorical, but neither would I say that they are not depictive of anything or are entirely abstract. I think I try to channel a condition or a certain state of mind, or some tear or tension that makes for the point of departure. They feel personal in that way.

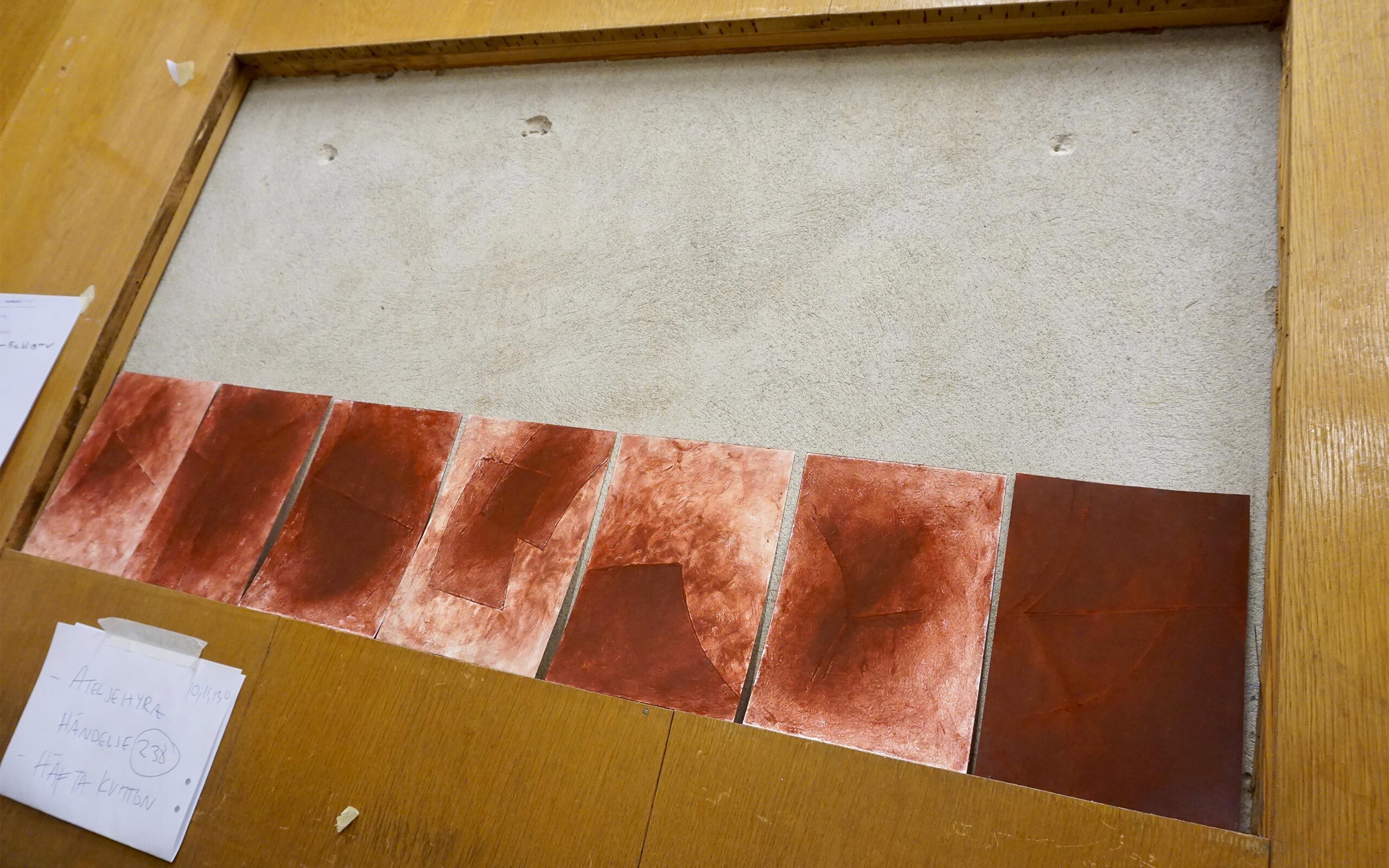

Your second but first major solo exhibition with Wetterling Gallery felt like a bold statement in so far as it presented primarily a single large-scale installation suspended in the air and occupying one entire room. Tell us more about that.

I had been entertaining the idea for a long time and had previously worked with groups and multiple units of works in exhibitions but that was the first time working with a main centerpiece in that way. A key component in this instance was having the luxury of a long period of time in which to work site-specifically at the gallery. I had two whole weeks to allow the work to gradually come into shape and place. Consequently, I became quite at home there and found the gallery to be a very safe and reassuring place in which to try out my ideas. Although there was a centerpiece, it was also the first time I presented drawings alongside installations and tried such combinations, even though they were shown in separate rooms.

What interconnection exists between your drawings and your physical three-dimensional works?

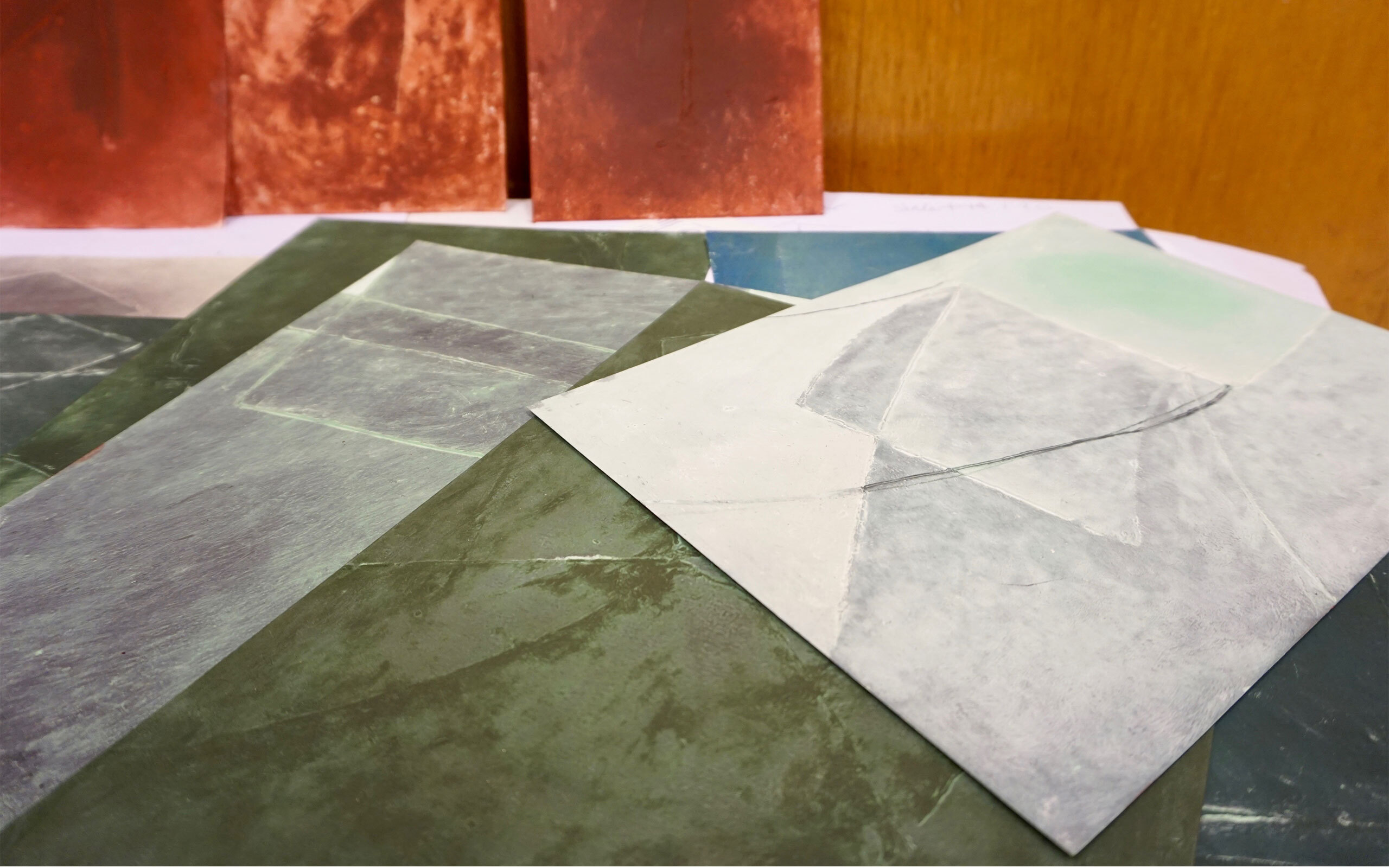

The unconditional focus and feeling that finds itself when drawing and trying out the form of an installation piece is the same, only the scale and material differs. Motif-wise the drawings of recent years have related to sketches of sculptures and installations. I definitely think these practices are related because there’s also a lot of emphasis on materiality and construction with the drawings that may not be immediately apparent. I work with both oil and dry pastel at the same time: once; there’s a balance between oily fat and dry layers on the surface where they continue to build each other up.

Who are some of the artistic role models that have inspired you?

That’s always hard question but I think of Eva Hesse and Eva Löfdahl. There was a Lee Lozano exhibition at Moderna Museet in Stockholm a few years ago that completely had me.

You belong to the school of emerging Swedish artists of recent years who’ve seen considerable success after art school, gaining acclaim with both the critics and the public. Does it come with a certain pressure?

I’m happy about the opportunities I’ve been given and the exposure I’ve had that have enabled me continue my art. I do feel pressure, of course, but I think pressure is inevitable in this field and I believe it can be an impetus that provokes you to be your very best.

Great things are coming up for you soon. Next, you have a group exhibition in Lima, Peru, at Revolver Galería, and then you will be exhibiting at the Armory Show with Wetterling Gallery in February. What will you be presenting?

In both Lima and at the fair I will be working with strip steel installations. In Lima the disposition of the venue resembles more an art museum rather than your typical gallery venue, with very high ceilings. The installation will be suspended high up in the air and there’s a balcony in the venue from where you will be able to see the installation more or less from eye level. There are safety measures to consider and everything inevitably gets more challenging to install.

Do you get nervous when in new situations?

Sure, I’m 100 percent nervous but I’m equally excited, and perhaps my nervousness is positive in an anticipatory way.

Interview: Ashik Zaman

Photos: Maria-Corina Wahlin

Links: Liva Isakson Lundin's website Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm