Barcelona-based artist Lúa Coderch likes to mention that she is a child of the Amazon River. If this information makes an impression on you, that is precisely the artist’s intention. Using research, Lúa Coderch’s work explores the surface of things and the materiality of personal and historical narrative. Using a wide range of media and strategies, she enquires into the aesthetic aspects of such topics as sincerity, enthusiasm, value, and deception. We visited Lúa in her studio outside Barcelona. She told us about how she had bought a mysterious container from outer space on Ebay, and we learned some lesser known facts about the German Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe, the inspiration for one of her most iconic works.

Lúa, we are in your studio, outside Barcelona. Can you tell us a little about this area?

My studio is located in an emerging area of urban Barcelona. We came here because the rent is still low. It is rather far out, so it’s not really Barcelona, it’s actually L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, that’s how far we are from the city center. (laughs) But lately the municipal administration, mainly in its own interest, naturally, has made great efforts to revitalize the community, for example by repurposing empty industrial buildings and offering them to design schools, artists, and other creative professions. These processes of gentrification don’t speak exclusively of progress and they are widely known in many other European cities. The district, though, is becoming livelier now, and I enjoy it here.

It’s a big building. Are you sharing it with other artists?

Yes, there are four other artists and myself on this floor in one big open space, and then another group of seven artists on the first floor. Unfortunately, I can’t introduce you to anyone at the moment since ARCO has just ended and everyone will be in Madrid for the rest of the week, I returned just the other day.

ARCO Madrid is the major artistic event of the year in Spain, right?

Yes, like it or not, almost everyone goes there to catch up on what everybody has been doing during the year.

Do you like to keep more to yourself or do you socialize with your fellow artists in the building?

I really appreciate having people around me here at work. They are my community, Rasmus Nilausen, Pere Llobera, Sebastián Cabrera, Martín Vitality. I usually prefer to work in a secluded place unlike this one, but I appreciate the opportunity to stop by and talk with them every now and then. I think they are very good at what they do, and I think it’s great to see and discuss what others are working on.

What’s this noise coming from the floor below, by the way? Sounds like someone is having a huge party.

(laughs) It is an African church, which was already here before we moved into the building. They are a very vital community. Today is a Sunday, so everyone gathers. It can get quite loud, but I think it’s good to have life in the building.

You give the impression of being a very thoughtful person. And the work we have seen from you is very profound in concept and meaning.

Yes, it’s true in a way. I personally think that art has always been about research. And I like to use art to research and reflect on things that are happening around me, about lectures, about the ways we relate to each other, and media plays a big role, too. It usually starts with something I discover that catches my interest. Then I try to find the same phenomenon in different places, or different representations of it. That process can result in a video, a text, a photograph, and sometimes perhaps even an event.

Are there some common themes, which inspire your work?

To be honest, in my early years, and they are not so long ago, I was looking for such a central motif, and I found my interests were so diverse that it was hard to keep track of them. It kind of frustrated me. It was only after a while that I discovered that they were in fact gravitating toward a few central ideas. One thing that really interests me, for example, is the notion of sincerity of things that appear to be true, but below the surface are false. Most of the things I am interested in are related to phenomenology. By that I mean how things appear, how they affect us in a direct way, which only later is then intellectualized. Another idea I like to reflect on is how value is created. In my view, value always has to do with distance. Images conveying exoticism and distance exert a certain fascination on people. If we cannot draw on our own experience, we tend to attribute value to the distant and the unknown. And I like to play with that.

Is that why you like to tell the story that you were born on the banks of the Amazon River?

Yes, exactly. Two years ago, I did this video called Gold. It is a videotaped narration on how value and charisma are generated and what is their relationship to distance, opacity and appearance. It began with the story of my being born on the Amazon River. What I find significant in this story of origin is not so much its unusual aspect, but its aesthetic efficiency.

You have already made us curious. So what is the story of your childhood in the Amazon?

At that time my parents were hippies and had been traveling around South America for some time. By the time my mom realized that she was pregnant they had been traveling up the Amazon River for three months... So they decided to settle down there and built a hut in a small community where they waited for me to arrive. This was in 1982, in a place called Santa Clara de Nanay, near Iquitos, where I only lived for a few months. I have no memory of it and don’t retain any link to that place. What I know about it is based on what I was later told and what I could make up from pictures. So for me that story is almost a lie. It has the deceptive quality of a story, which fascinates me. There is potential to develop more from it.

Did you grow up in Peru then?

We moved to Brazil a year after I was born. When I turned five, we arrived in Spain. I think it is at the age of four or five, when kids start to develop their own memory. About that time my parents started telling me that I was born in a distant place. The idea struck me so much at that early age and I remember telling other children in kindergarten the story that I was from Peru. My story always made me a foreigner.

How did you become an artist?

You know, I was actually studying to become a lawyer and I attended the first few years of law school. Many members of my family work in that professional field. I almost completed my degree, and there were only two subjects left I think. After the first year of law studies, I began studying sculpture at the same time. I never finished my law studies because I gradually spent more and more time and effort on my art work. I never made a decision. So I somehow just drifted away from law in favor of sculpture.

How do law and art go together?

Studying law let me develop that abstract sense of the world. In law everything is understood in terms of material proof, but that proof relates to an abstract form. Everything around us can be read in terms of legal formulas. A certain gesture can be interpreted as a contract. A certain act or even a certain statement can be read as a crime. I think I have been able to apply some of what I learned at law school to art during those years.

Would you consider yourself a sculptural artist?

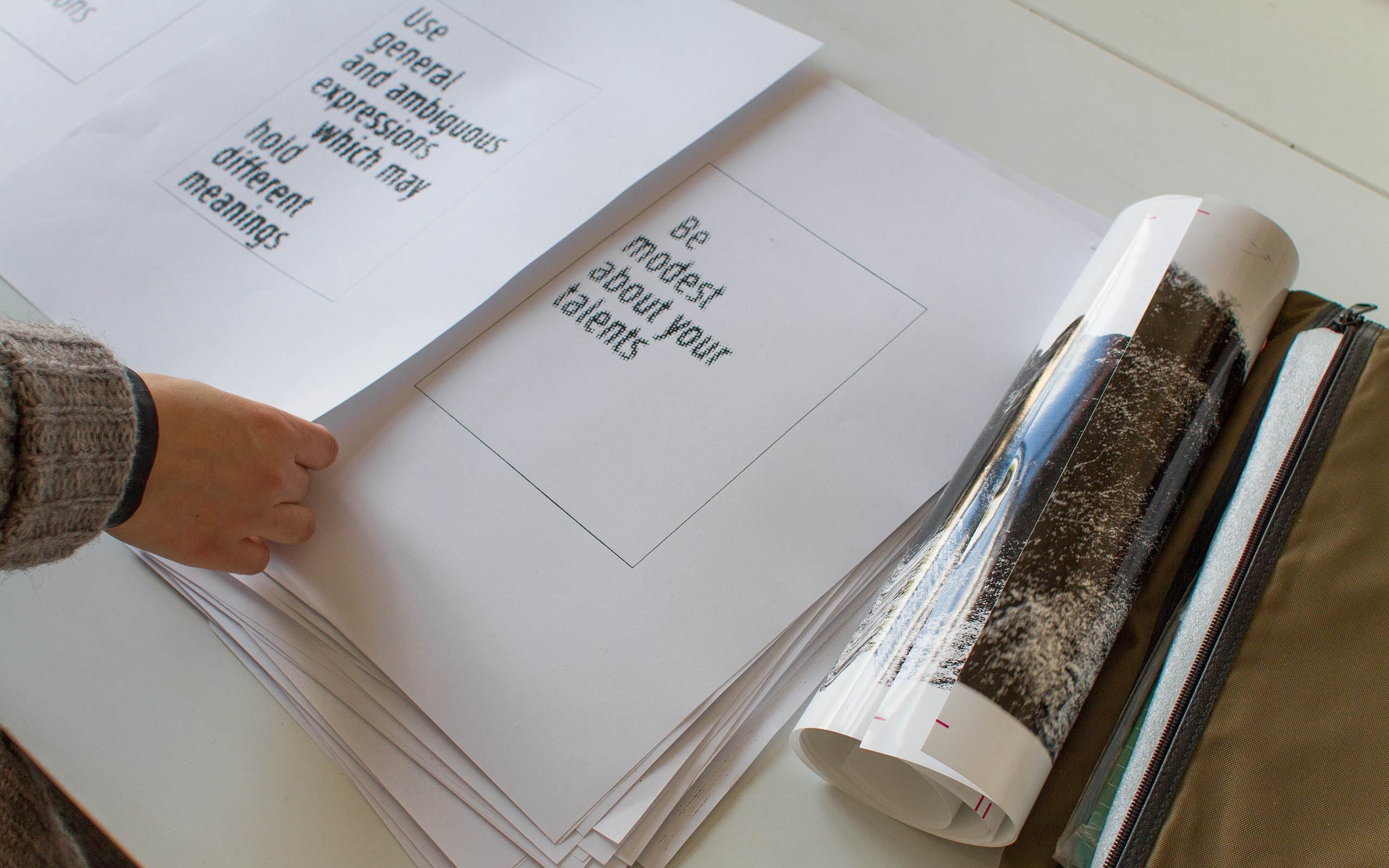

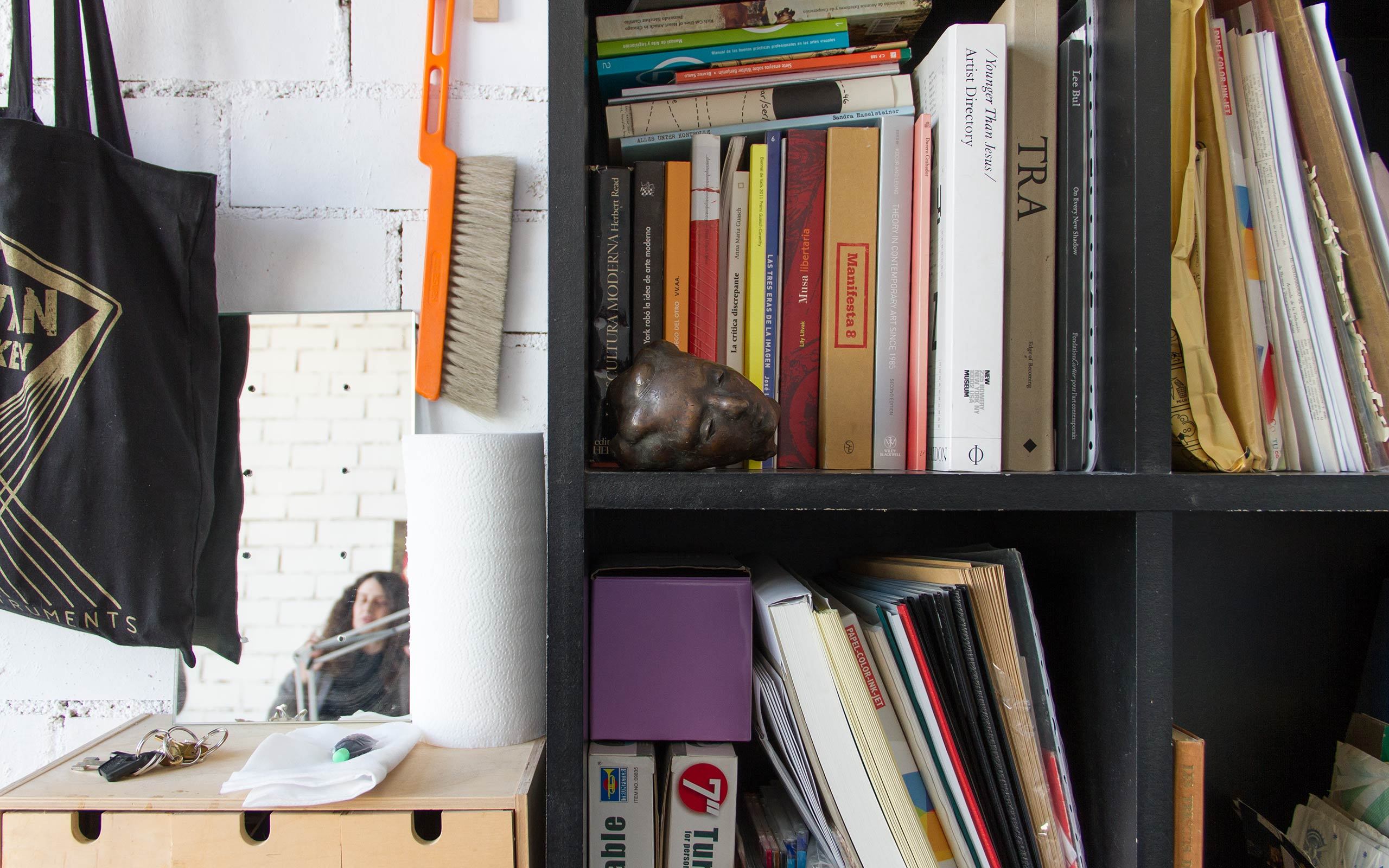

I used to be pretty much a classical sculptor. I was trained to work with stone and bronze at a very conservative art school that taught the formal principles and basics of the craft. For example the small head sitting on the shelf is a piece I did during that time. But at some point the discipline of classical sculpting weighed heavily on me. I knew my craft well, but I didn’t know where to go with it. Now I am practically working with all media. But there is definitely an affinity shining through, which is to “display”. I really enjoy the act of designing and working with materials and objects as much as with concepts.

You had a major show in 2014 at Fundació Joan Miró, called “La montaña mágica,” where the idea of “display” was very prominent.

Yes. For that exhibition I built a big warehouse on the premises, using up half of the exhibition space to store things, like stage props in a theater. That warehouse was open for a few hours a day only, remaining closed during the rest of the opening hours of the museum. Behind the scenes, in the warehouse, I worked to prepare a new exhibition each day, composed from objects, video, audio and photographs, and also archival material I had collected. The exhibition lasted for 72 days. That was quite a tour de force, I can tell you. (laughs) Each day, I tried to develop a different line of research, to explore how the city of Barcelona evolved, and how the city built its memory.

One of your most impressive case studies at “La montaña mágica” was a life-size reproduction of the onyx wall from the German Pavilion in Barcelona by Mies van der Rohe. Is that also about “memory”?

After the end of the Franco regime, Barcelona sought to connect, or find a link back to modern history, back to the pre-war years, as a way to distance itself from the forty years of dictatorship and ostracism. As a part of this process, it was decided to rebuild the German Pavilion, which was originally designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1929, on the occasion of the 1929 International Exposition. Barcelona wanted to catch up and reconnect to what was happening in the rest of modern Europe, retaking that thread. This inspired me to call it International Style (onyx wall), in reference to the architectural style that emerged in the 1920s and 30s.

What is so specific about the Mies van der Rohe Pavilion that it influenced one of your works?

You have to know that the Pavilion was demolished in 1930, after the close of the International Exposition. As the years went by, the Pavilion became something of a myth. That was a major reason to undertake the reconstruction. But during WWII the original building plans were lost, so the reconstruction is entirely based on the surviving images. A reconstruction from an image feels to me like a ghost. On the other hand, during the Franco regime, another pavilion was built in the area. So when the German Pavilion was rebuilt there was also a huge brutalist pavilion with little architectural value at just a few meters distance from it. With that other pavilion so close, nobody could carry home that picture-perfect, iconic image of the rebuilt Mies van der Rohe Pavilion. So they cleared the space around it and demolished the other pavilion… Barcelona has always been accused of being just an image. It’s a touristic city.

Why did you choose to reproduce specifically the onyx wall?

The onyx wall is the centerpiece of the Pavilion. Mies van der Rohe conceived his entire plans around this central wall – it represents the heart of it all. So the wall carries a lot of symbolic weight. As for the inflatable wall, for me it best represents the irony, the complexity and insincerity of that whole story.

International Style [Onyx Wall] at Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, 2014. Image courtesy of Fundació Joan Miró © Pere Pratdesaba.

International Style [Onyx Wall] at Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist.

You mentioned the dictatorship of Franco. One of your works called The Palaces Left Behind also deals with dictatorships.

Yes, for that project I had collected images from the palaces and residencies of dictators such as Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein or Ceauscescu. It is not primarily about the fact that they were dictators, but that they were distant, unreachable for the common people, which created a myth around them. When people like Gaddafi had to flee and leave all their belongings and luxury behind in a hurry, their absence attracted looters of course, and also the curious. For the first time, common people were able to enter these places, which had previously only existed in their imagination. Finally being able to access the private quarters of their former ruler, they felt an urge to document, take pictures and videos of the objects and spaces that represented the kind of life that was led there. When Rosa Lleó of The Green Parrot asked me to take part in her exhibition, it was called The World of Interiors, I wanted to do something with these pictures, these documented objects. I created a curtain with a pattern made of the objects I found in this photographic and video footage.

So you are a researcher, but also a collector?

I don’t feel like a collector, because I am using these objects for my work. But in a way, yes, I guess I am a collector, too, because sometimes it takes a while until something I collect becomes part of an artwork.

But you are definitely a story-teller.

Yes, I am very interested in stories, and how an object can trigger a story, or how a story itself can even become an object. I have been collecting short stories, which can be used as objects to start a conversation. They are like little parables. I once found an object on Ebay, a canister allegedly containing a roll of undeveloped film. The seller claimed that the film had been on a Russian space mission in the 1980s. I decided to place a bid not expecting to win the auction, I anticipated that lots of people would bid on this intriguing and amazing piece. The thing is I won! In fact I was the only one to place a bid..., which felt kind of suspicious, I guess. It was 124 Euro which you may consider expensive, or not, depending on your viewpoint. If the item turned out to be genuine I felt the cost would be good value for such a great story. I kept this object for a whole year not knowing what to do with it. In a way I shied away from opening the container because I was afraid of being disappointed.

What did you decide to do with this mysterious container from outer space?

I realized that the unopened container was really good to start a conversation with people, and also that people were very quick to make suggestions as to what to do with it. Some people couldn’t believe I hadn’t opened the canister already. Others felt that it was much better to keep the canister closed and keep it as a mystery. I decided to send out an open invitation, but limited to 30 people, and organized an event at which we would decide collectively what to do with the container. If the decision was to open the canister, this would be put into action immediately and a photographer was present and a small darkroom set up so that any film found could be processed. In the end, the object was only an excuse for the gathering. People were talking about all kinds of things, such as love, disappointment, bravery, or cowardice. The object did its work as a facilitator, but ultimately human curiosity prevailed and the group decided to open the canister. (laughs) And it was true! It actually turned out to be a film from a Soviet space mission. The images were a bit disappointing, because the contrast was poor, but you could see the sunrise and parts of the space station. Anyway, this is something that, for now, remains among the small group of people present.

It has only been a few weeks since you became a mother. How do you expect your job as an artist to change from now on?

Well, it is probably too early to say, this little guy has been among us for only a month. I am about to start working again. Just now, looking ahead, it feels a bit scary. The thing is that in this very small artistic scene, among women artists there are few role models, who would show us how it can be done. Let’s say we have just a few, very valuable, ones. We should ask the same questions of male artists as well, I suppose. One thing that is clear to me now is that a child renews your sense of community.

What are your plans for this year?

I have a big project planned called Shelter, which involves a lot of travel internationally. This trip in the summer will take my team and me (including my kid and my partner) to different places where we will build debris shelters in the outdoors, made of things we will find. Later I will write about the experience of shelter building and of related ideas, including collecting, material memory or/and how we inhabit and orient ourselves in the world. Again, as with the unopened container, the shelter itself is only an excuse to open a conversation

Ausschnitt aus Gold, 2014; Digitales Video in HD, 28’43”

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer