Madeleine Boschan’s sculptures make visible layers of historical, emotional, and spiritual aspects that characterize all manmade locations and spaces. In recent years, the artist’s work has developed from working directly with everyday objects and objet trouvés towards an impressive chromaticity. We spoke with Madeleine in her studio about this development, her career which began in sports, travel, and how she finally found her way to sculpture.

Madeleine, we are in your studio in Berlin-Adlershof, quite a distance from the center of the city.

It was once the headquarters of the regimental guard of the former GDR and during WWII my grandfather was stationed here. I like to be out here. In the Spring I like to ride my bike out here. The further I am away from the City the more relaxed I become. At the same time, it is a good contrast to work in the Neukölln office. The architecture in this neighborhood is great. Adlershof was the location of the first German airport. Today it is the site of the DLR (German Aerospace Center). In the early twentieth century, experimental structures related to aerodynamic research were constructed, these included the Trudel Tower and the gigantic wind tunnel. Today, they are landmarks and people use them as meeting places. That is one of my topics: Where and how do people come together? How do encounters occur? There are no plazas as in Italy or Greece.

Wouldn’t you prefer a studio in chic Berlin-Mitte or in Friedrichshain?

Well, I would not say that I wouldn’t, but the empty, as yet undeveloped areas and sights are inspirational sources. For quite some time, I had my studio in Friedrichshain and always perceived it as being too narrow although it was actually a big studio. For my work I need space – in my head and when I go outside. Also I like the solitude here.

So the established is not for you?

I travel a lot. I try to be in places that I don’t know – for both inspiration and to gain distance. As a child, I traveled a lot with my parents. Various social structures were influential. However, I always like to return to Berlin and try to give the new impressions a form.

You said that the joy of travel came from your parents. Does that also apply to art?

My father was a systems analyst and inventor. He always said when he hears someone say “it isn’t possible”, to him it actually means there is nothing that is “not possible,” nothing that could not be invented. But he was also the one who said that my mother was always right even if she was wrong. With my grandparents I frequently visited museums and exhibitions.

Furthermore, your development toward art was not really straightforward because you actually began in sports.

I was a gymnast: floor exercises, high bar, and balance beam. I participated in competitions until I was sixteen. The physical experience of running through an almost empty space, to take a run-up for a jump, then come to a full stand while keeping your balance, to precisely position yourself and to see in which direction to expand, I am still in search for that. For me the main goal in art regardless of whether in architecture, sculpture, or painting is to communicate a sense of the location so that the artist and the viewer know where they are.

Is there a reason why you gave up high-performance sport?

To exercise continually in the same way was not for me.

How did you become a sculptor?

I studied painting and photography in Brunswick. In my early studies, I worked with large-size collages and got deeper and deeper into space. After I received my diploma I moved to Berlin. From that time I photographed using only film in large format, exploring the city in this way. My topics were mainly architectural, shadows and color. And yet I found that there was too little physical challenge in that work. And on my walks with the camera I noticed the numerous piles of bulky waste.

When did you develop your first sculpture?

That was in 2008. At the time I was invited to participate in an exhibition with the theme self-portrait. But since I neither wanted to paint a self-portrait nor shoot a Selfie, I simply built a sculpture. Mind you: it stood on two legs and had the title “360.000 Possibilities (stronger and weaker ones)”. I liked that, especially because the space around a sculpture becomes a location.

Here in your studio there are only models. The originals are huge metal works. Do you weld them yourself?

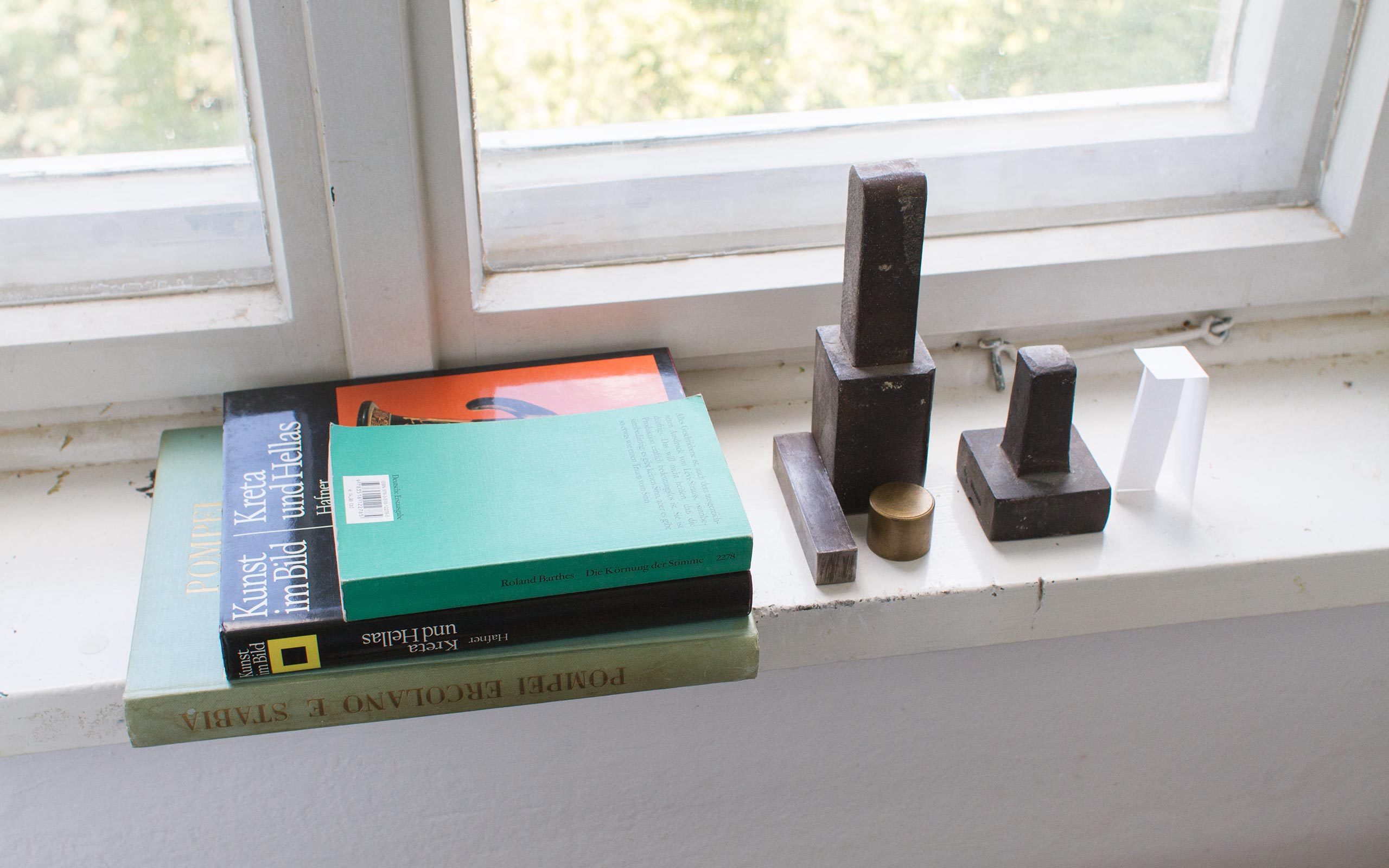

There is no difference between the model-like character of a small work and a large one. The idea behind it is inherently utopian in all works and the respective proportion and size is developed from the entire structure that is or was provided to me as the space in which to compose the work. The larger works for interior spaces don’t have to be welded they balance each other through the degrees of their angles. Once in a while I collaborate with a firm that folds aluminum sheets according to my designs and plans. I treat them with color myself, because I want to have my vibration in the chromaticity.

Viewed from various angles the character of your sculptures changes considerably – from one perspective they may appear fragile, from another quite massive.

A minimal change in angle changes everything. Something becomes narrow or wide. We human beings also have a more narrow and a broader side. When Bruce Nauman in the 1960s walked in his studio in precise rectangles, it was certainly a physical experience, but it was also an affirmation of his own existence.

On the one hand your works appear as if one had never seen them and are yet somehow familiar. I don’t know why this should be so.

I can’t tell you either. (laughs) Neither can I say where to begin looking or where to go to next. I can’t decide this for someone. Everyone has to find their own place. Perhaps this is rather a feeling of familiarity, which however one should be wary of trusting, both the directly physical and the societal feeling. The feeling of estrangement – towards oneself and others – is part of recognition. To be both accepted and to trust oneself is a complex process. The experience may proceed more quickly, but it has little to do with to what extent one would be aware of it. Ultimately everything is a novelty. Art is not simply a mini-golf course on which one proceeds successively from one hole to the next.

One of the reasons may be that your works sometimes appear very archaic, sites of a past culture.

I am glad that you perceive it like that. For me it is as if the sculptures are being loaded by their environment and the people who look at them. They function as memory. It is indescribable, one simply feels it.

How do you approach such works?

My starting point are questions: Where am I? How do I orientate myself? When I plan an exhibition I want to know everything about the space and the location – historically and architecturally. A bit like the strategic spying out of unfamiliar territory before an invasion. To give the sculpture its place has always something to do with occupation. I walk the space and develop a range of sensorimotor sentiments and impressions and from that results my approach to the work.

History and specifically the history of architecture are a great inspiration for you?

Without a context one has no stance. It’s not just about physics. For me social and ethical questions are important. Where and how are encounters possible? Is it even possible that one can come together? An idea of connection possibilities, not one without the other, togetherness.

Do you have specific references in terms of architecture? Or do you create your own places?

No, I don’t have specific references, although my preferences are for Greek and Japanese architecture. I admire Gropius, Niemeyer, van der Rohe, Wright, but the sculptures with their perspectives and angles are all mine. I first explore with card models how something functions, what stands on its own and which angles are to be chosen. Then I build larger with plywood or plaster. This way I can go to extremes, adjust the angles until it holds and in doing so, explore the vocabulary of form.

Can you imagine that your sculptures could functions as buildings?

As a monument or meeting place, yes. But please without glass walls or toilets (laughs). I imagine my sculptures as concrete exterior places. Instead of the TV tower on Alexanderplatz one could simply meet at the green portal. (laughs)

We have already touched upon traveling. As an artist one also has the possibility of a “residency”. What do you take from such a place with you for your work?

Patience, impressions, emotions, new questions and problems.

At some point you started exploring Oceanic and African art. How might one see a bridge to your work?

Before I began studying, I had met a couple who collected sculpture from Africa and Oceania and so they provided an introduction to these art forms. I was immediately fascinated and began to research intensively their ritual aspects and linguistic and societal significance. I am still interested in complex systems of living and in various societal interactions. I own a small collection of figures and everyday objects that I have been able to afford, mainly from the regions of the Ivory Coast and I am constantly astonished on the one hand at their elegance and on the other from our “Western” perspective, their bold and even grotesque language of form.

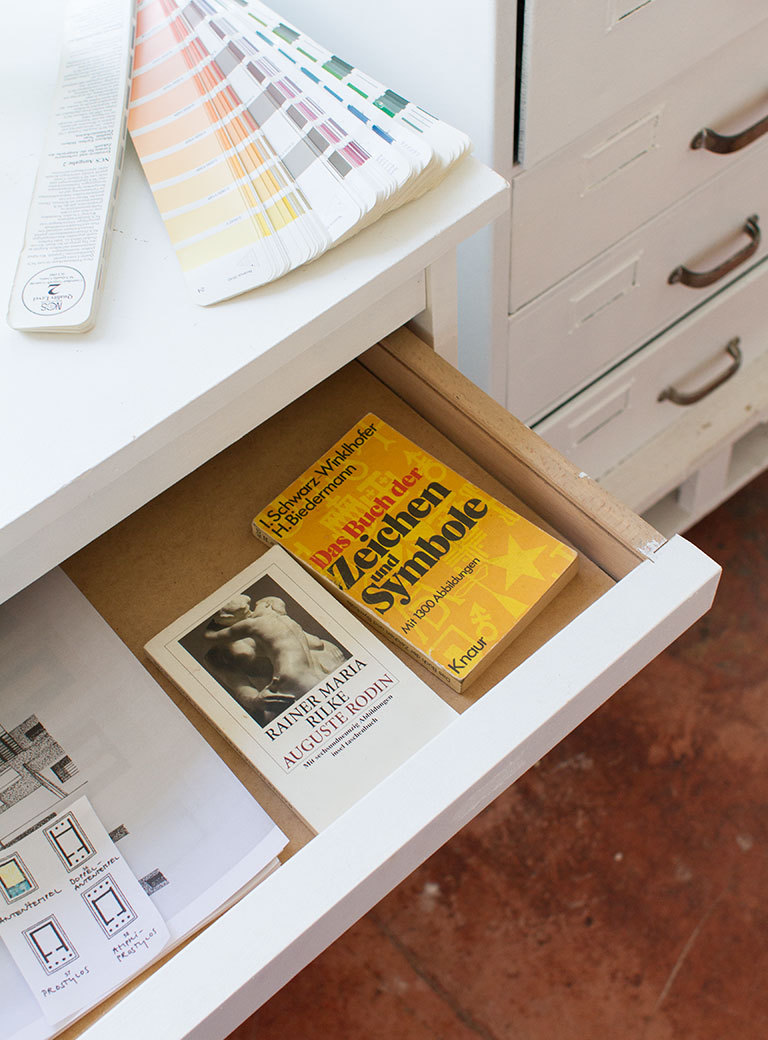

A further source of inspiration for you is literature. How do you translate this literary inspiration into your sculptural work?

The extent of the relationships of various bodies in an extreme spatial situation poses the elementary question can a body be present in isolation? This example derives from Beckett. In Frank O´Hara’s work on the other hand there exists a palpable correlation between exterior and interior experience. His precise everyday observations are paired with a subjective self-statement. Here the fission between the world and the subject (the I) becomes apparent. And it is also clear that they belong together. Therefore the question is, how do we actually fit into the world without losing ourselves? The interrelationship between the sculptures and the poems can be understood as in every relationship. What touches us, what moves us? That which is near, that which is far? That which is distant or that which is intimate? Is there a togetherness that is present or rather absent? In this space of resonance there develops an esthetical experience that poses the question: who questions, who speaks, from where, and who addresses whom? The sensibility for the concrete reality and for the equally existing abstraction has a resonance in Rainer Maria Rilke’s malleable thinking. During his time in Paris he had been Rodin’s secretary and among other things wrote his New Poems from this experience.

Also colorfulness plays a large role in your work. Which concept are you pursuing with the color you choose?

Here too the location provided is a decisive factor. The sculptures that were shown in the Neue Galerie Gladbeck in 2015 have a direct reference to the color of Miami’s Art Deco architecture and the colors of the 1980s – Miami Vice for example (laughs). The color of the works that I showed in my gallery in Tel Aviv in February 2016 originate in antique polychromy. Essential to this was the discovery of an antique Greek temple underneath a parking lot in Jerusalem as well as the acknowledgement that spaces are always culturally and historically changeable. The term “antique polychromy” goes back to the eighteenth century. Until then, it was not known that temples and statues had been painted. One rather followed Winkelmann’s classical beauty ideal that only the pure white could reflect sunlight in such a way that the beauty of the bodies were best presented. This was complete nonsense and more precise studies kindled the so-called polychromy controversy that lasted until WWII. It was Vinzenz Brinckmann who proved with modern methods of investigation that the sculptures and temples were originally colorful and that even the Acropolis was covered with green, ochre, pink, violet, and light blue.

That was a shock for many, because the Greek temples actually look very nice in white.

Yes, so elevated that one stuck to it for years, arguing it had only been a barbaric, Etruscan custom to paint sculptures colorful. After WWII, the discussion ebbed down. No wonder therefore, when Winkelmann’s marble white, antique monuments had become so completely ingrained. The color concept, however, was not a minor matter as the color palette and rich ornamentation of the sculptures and temples show. The cult wanted to come as close to reality as possible. It may be compared to the porcelain figures and scenes that adorned baroque tables set on mirrors being lit by candlelight. It was a lively, playful world. In antique Greece it signified the direct cohabitation with the gods.

What’s next for you, Madeleine?

I work. At the moment I prepare my next solo exhibition for Galerie Bernd Kugler in Innsbruck that will open in the beginning of June. Here I am producing five new walkable sculptures from sheet metal that take the viewer into the center of intimacy and conflict, closeness and distance. The viewers can enter rooms that are formed by various sculptural modules, which I will develop from human proportions. I am excited myself which kind of action and communication possibilities will be provoked! And in the meantime I work on paper and plaster models for an exhibition next year in Zurich, think about brutality or listen to Pergolesi.

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer