In her practice, Maruša Sagadin investigates the interplay between gender, language, and sculpture in modern architecture. Her installations and objects function deliberately in both the interior and exterior space, referring to elements of pop and subculture, working with humor and exaggeration and are often expanded by a performative act in order to invite viewers to participate actively in her art.

Maruša, before starting your career as an artist you were active as a professional athlete for thirteen years. How did this career change occur?

For a long time, I was an active skier in the Slovenian Alps. When the former Yugoslavia fell apart, I went to Austria and continued my sports career playing basketball. I quickly qualified for the Bundesliga. An offer to play for the Austrian national team got me an Austrian passport. This was very relevant, because it opened up new educational and professional opportunities that had been closed to me before. I studied architecture in Graz and sculpture in Vienna. Sport has done a lot for me.

You connect architecture and sculpture. Where do you begin?

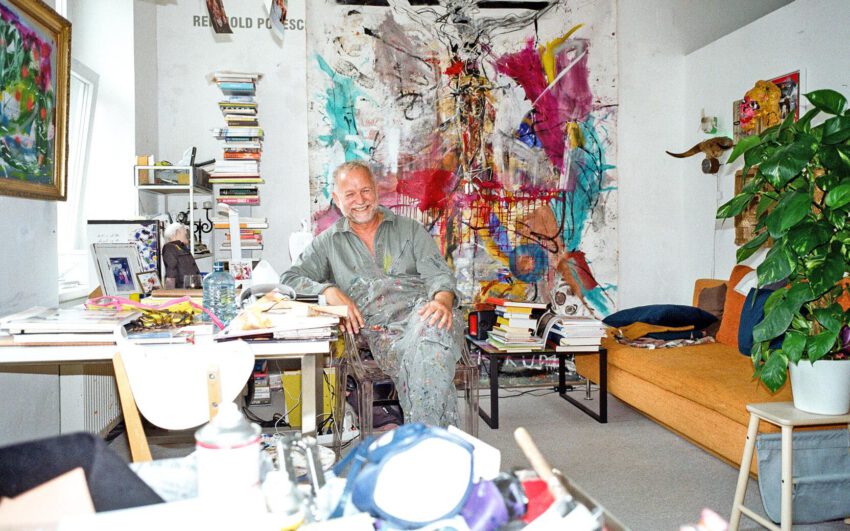

My work derives from architecture, however I do not build living space but transform the notion of architecture into something new, constructing experiences and projections. With this approach I can realize my artistic work without having to compromise and am able to investigate the social aspect of architecture.

What social aspect of architecture do you mean?

The social aspect of architecture addresses the questions: who builds, where and for whom? Who is actually in the position to build? This addresses the mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion in architecture. In addition, gender questions play a large role. I am asking the question, according to whose norms are we building and does this give rise to specification? With the creation of a sculpture following architecture I would like to break with norms and structures. Consequently, I use the same materials for sculptures built for the interior and exterior spaces. What you find in the “white cube”, you find in the street. This way what appears inaccessible in a space becomes freely accessible outside the space.

What other strategies do you use in order to break with the norms of architecture?

In my strategies I break with size and color. Often my objects communicate some use although they are too heavy and too large to actually be used. They are unbearable and intolerable. In my color choice I select combinations that easily miss normative “good” taste. The intention lies in escaping from a kind of complacency which could also be read as a confrontation which is necessary for a successful breach.

Your works appear almost like a “cartoon language”, are heavily lacquered and allow one to only guess the material used. What materials are used and in what way?

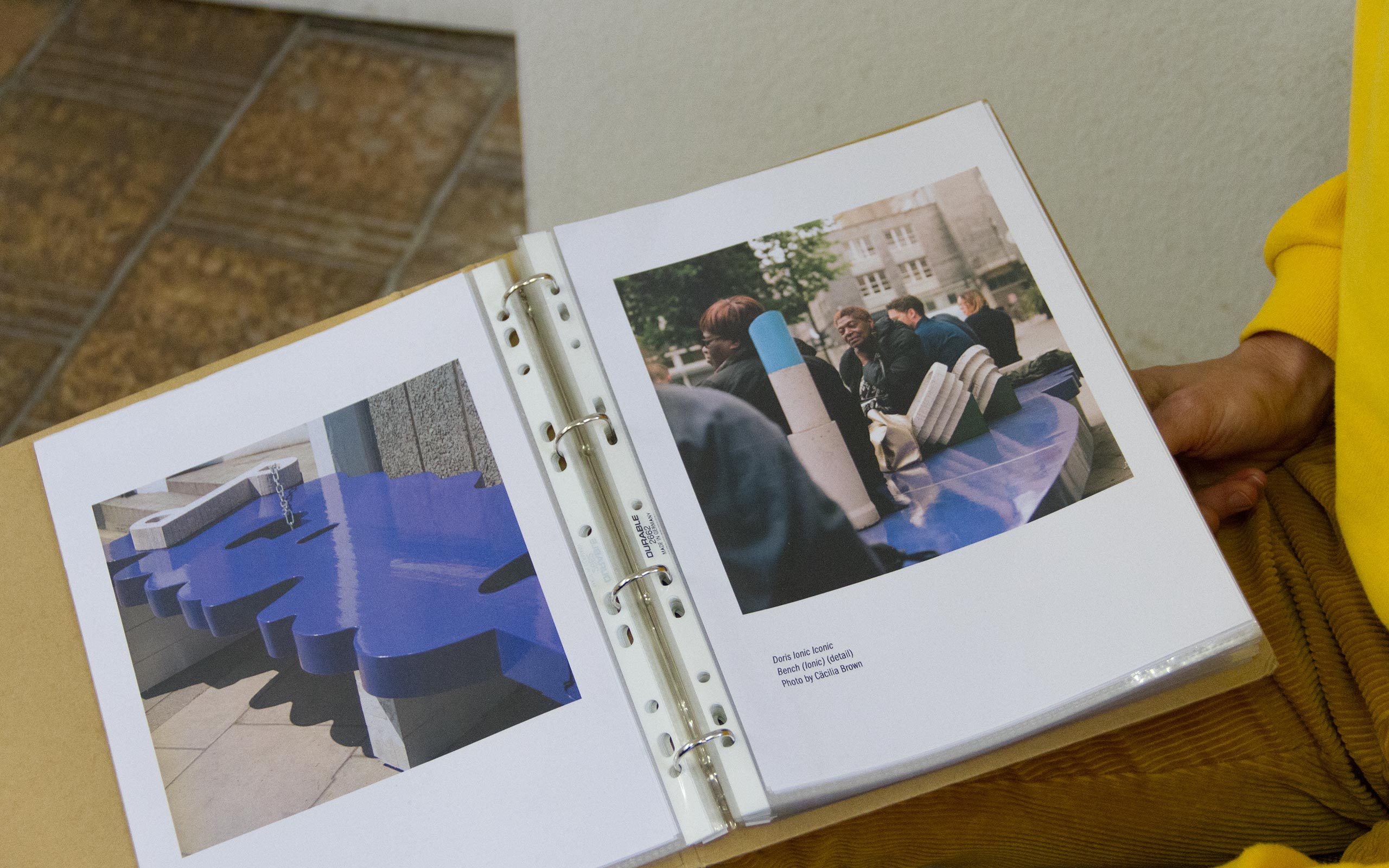

The main material is reasonable quality spruce, which I rarely present as wood. I always cover it with a strong opaque surface color because I don’t claim to show the truth but want to create a “fake”. It is comparable to an indelible makeup which has been applied in excess and therefore almost hurts. It is also about reflection, a kind of high gloss for the poor. Other materials that I use are the classic architectural construction materials like concrete and polystyrene. The ‘cartoon character’ aspect results from various themes and opposites that I allow into my work, including youth and underground culture, music culture, and the contrast between high and pop culture. This shows a certain “trashy” aspect which I like to use. In order to present expertise within pop culture in detail I exchange ideas with those in the music scene, curators, and DJs, who then become part of my work. My current exhibition Tschumi Alumni. How Culture Works. How Art Works at Kȕnstlerhaus Graz is complemented by a sci-fi-like essay by curator Mette Woller which investigates such phenomena as “hydrofeminism”, and the late musician Prince. It will be accompanied by a DJ set by Juliana Lindenhofer, who will perform on my outdoor sculpture, Doris.

The lacquer colors of your sculptures are especially strong. What’s the significance of color in your work?

In my selection of color I try to avoid explicit associations and place colors in new contexts. How can I change the political meaning of blue and turquoise? Can red be something else than socialist? And what do I connect with orange, more the 1980s or the revolution? What is feminist and not feminine in pink? For my exhibition She in Caps at König2 I lacquered a sculpture blue and titled it das Herz in der Hose [The Heart in the Pants]. Its combination seems to be fragile and its positioning perhaps not empowering. It appears reserved and pushed toward the margin, a failed representation, because one is only as strong as one presents oneself and perhaps during that self-staging, one’s “heart drops into one’s pants”.

Your work Doris, an over-dimensional bench and walkable sculpture is painted purple. What statement does this color make?

The color refers to feminist statements, at the same time and in contrast it is the color of spirituality. By the way, Prince’s song Purple Rain is the most beautiful song about the color purple. In its shape Doris is reminiscent of Doric columns, the simplest form of the Greek column system. Doris, while columnar, lies horizontal in the form of a bench seat, breaking with such attributes as power, greatness, and representation afforded by verticality. It can be used, offers a ‘high-gloss’ surface to sit or lie on and is freely available in the public space.

Through the form of your sculptures you also communicate gender forms. Some look like a lipstick and the piece Milli Bofilli is reminiscent of a high heel.

Many architectural forms are reminiscent of objects with which we are familiar and are then named accordingly: iron, tongues, shoes, or waves. My works Lipstick Building and Milli Bofilli are games of seduction and self-empowerment. The case of Lipstick Building is a reference both to makeup and the façade of a building. Questions of power, greatness and splendor arise for makeup is used to make something appear larger. One part of Milli Bofilli is a high heel that can’t be worn but the form of which still appears seductive. With Extra Extra Elle I built a series of model-like objects that are reminiscent of high heel shoes and the form of which is inspired by the architecture of Zaha Hadid, particularly the Bergisel ski jump.

Many of your works reference each other. Your lipstick sculpture is often exhibited in conjunction with Doris.

My works complement and support each other like “props” on a stage. In that regard they are editions of my works. Some things must stand on top of each other and sometimes I need a certain object duplicated to show both at the same time. This is the case when my sculptures are shown simultaneously in more than one exhibition. Therefore some works exist as two or three examples.

Your works undergo a continuous process of revision. Much is renegotiated, remodeled , or even completely destroyed. What’s that about?

I can’t store all of my sculptures, sometimes because of lack of space, sometimes because they are not good enough. Some works that I have already shown, can lose their focus or tension and appear no longer pertinent. Then I try to rebuild the tension by reworking, repainting or cutting the pieces. The old work does not disappear completely, but is still visible in the new work as for example in A Happy Hippie (Happy stories are all happy in the same way and unhappy each in their own way). It is like an ongoing evolvement. Once I felt almost embarrassed about this process in my art, but now I would say that it has become a part of my artistic practice.

As an artist you taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna for a long time. What influence did this experience have on your work?

Teaching at the academy was like a form of further education for me. It keeps you fit because it is a constant challenge to provide your students with new impulses. There was a good deal of give and take. I received an enormous amount of input from my students and colleagues, but one should stop when it becomes a routine.

What architecture excites you and your work as an artist?

I like North American architecture and the city of Los Angeles. Los Angeles is immediately associated with Postmodernism as well as with a breach with the logic of Modernism and European urban culture. In my architectural studies, we were downright bombarded with the truth of Modernism and the opinion that Postmodernism was substandard and the inferiority of Postmodernism. But I love one’s own logic, kitsch, exaggeration, fakeness, and the sense of irony in Postmodernism. It leaves room for insignificance and ambiguity leading to the question of alternative identities.

Gender and questions associated with gender are concretely dealt with both in your work and your life. What is important to you in that regard?

One aspect in this regard is visibility. Sculpture is already a form of making something visible and because I transform content, images, and concepts into objects and haptic material in order to create a “remix”, I already show something that can’t be overlooked and demands its place. In my references I consciously search for content that breaks with the “mainstream” or shows the “mainstream” in a different light. In my previously mentioned exhibition Extra Extra Elle one asks oneself whether a prominent and once ubiquitous personality like Zaha Hadid to whom I attest as a focus, needs an additional stage. Perhaps not, but one must emphasize again and again that to date, she is the only female Pritzker Award recipient. That does not explicitly say that works about and by Zaha Hadid are “queer”, nevertheless through her example one can demonstrate many discrepancies and contradictions. The relentless search for new theories and approaches is an enormous stimulus. And I often make discoveries in the younger generation or through my esteemed colleagues Cäcilia Brown, Toni Schmale, Stefanie Siebold, Gabriele Edlbauer, to name just a few.

What do your exhibition plans look like?

Currently works of mine can be seen at Künstlerhaus Graz. At the end of May I cooperate with the artists Cäcilia Brown and Noële Ody on a sculptural setting for the Foyer of 21er Haus, in the context of the Public Program. An umbrella-like sculpture in the form of a “Cap” will be shown in Vienna’s Tenth District in September 2018.

A Happy Hippie

(Happy stories are all happy in the same way and unhappy each in their own way), 2017

Wood, metal, concrete, paint

A Happy Hippie

(Happy stories are all happy in the same way and unhappy each in their own way), 2017

Wood, metal, concrete, paint

Das Herz in der Hose, 2018

Wood, concrete, paint

Das Herz in der Hose, 2018

Wood, concrete, paint

Milli Bofilli, 2018

Wood, metall, concrete, paint

Milli Bofilli, 2018

Wood, metall, concrete, paint

Interview: Alexandra-Maria Toth

Photos: Florian Langhammer

Exhibition views of She in Caps: (c) Paul Knight, courtesy Koenig2_by robbygreif