Miao Ying has always incorporated technology in her art. She began with exploring how it enables censorship in China, which she addressed via the primary language of the contemporary Internet, humor, in addition to its other related attributes including lo-fi visual elements, kitschy pictures, and GIFs. Lately, Miao has sought to curb artificial intelligence and to find ways to collaborate with it. The negative aspects of AI aside, there is an element of magic to it, she says.

Ying, you were born in Shanghai and grew up with the Chinese economic reform that opened the country up to foreign investments and technology, the rise of the Internet and the country’s one-child policy. How would you say this has influenced your work?

My generation grew up with the Internet and the personal computer. I’ve always felt that there is a bifurcation in place because there is heavy censorship in China therefore while the internet is a tool for exploring the technology also exists as a tool that enables the suppression of unregulated exploration. I witnessed how it was developing even before Google existed in China, how it evolved with the rise of social media platforms, and how the government cracked down on the Western platforms which were then replaced by local tech companies. At that time in 2010, my work was focused on self-censorship. Because there are limitations in the use of the Internet, people are able to evade censorship by for example creating memes, a form of human creativity that came into being as a result of censorship. As a foreigner I am looking at the Internet from a different perspective; people are aware of what they are providing to the algorithm, and when I’m typing I self-censor and I’m very careful, while in the West, people believe that they have freedom of speech.

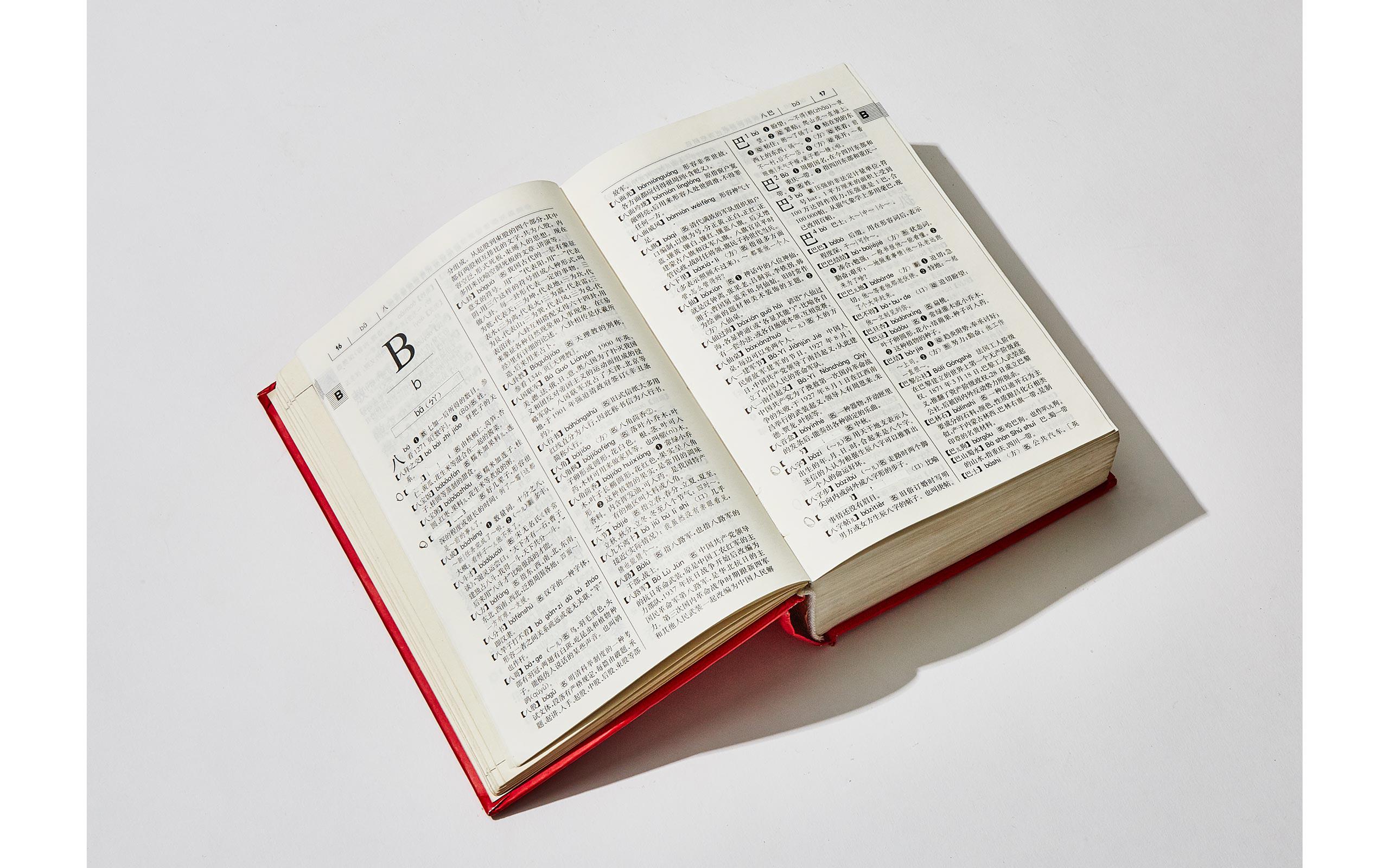

Your first artwork Blind Spot in 2007 was already a major statement against censorship. It is an 1,869-page Mandarin dictionary that has been manually annotated to indicate how many search terms were censored in China at the time. How did you come up with this idea and what was the result?

Of the 56,000 entries, 2,000 had been censored as Internet search items. I learned in the news that Google was entering China and had agreed to censor words that the Chinese government didn’t want people to see, and it was assumed that few would make the effort to find out exactly what was on the list of censored items. I was about to graduate from college and preparing for my thesis presentation and I wanted to know how extensive the list was and what the offending words were that the government considered necessary to censor. This work really interested me not only out of curiosity about censorship, but that in order to complete this task, I had to work 10 hours a day, manually repeating a simple procedure that would normally be done automatically by the program and which therefore pushed me to my limits of being a machine. It was more of a performance piece, forcing myself to keep searching; I tried not to think of a reason a given term might be censored, just to annotate it in the dictionary as something that would be erased from the dictionary.

How long did your work on Blind Spot take?

I worked on it for three months. Interestingly, there were 2,000 censored words in 2007 but in 2008, there were only 80 because there were many foreigners in China for the Beijing Olympics and the government wanted to downplay any controversy regarding censorship. In 2010, Google eventually left China. Every time I talk about this piece in the US, the public’s focus is only on the aspects of censorship in China. But that’s not the whole story as it is also about how the Chinese tech companies themselves do business. Since Google left, there is now a duplication search engine called Baidu, which is more stringent than Google was. When you searched on Google, if you entered an item that had been censored, a message would appear at the bottom of the page stating, “According to local laws, this result has been filtered”. On Baidu, they don’t tell you anything, they just censor. Google never closed their office in Beijing and have been trying to re-enter the Chinese market. A couple of years after leaving they created a modified algorithm called The Dragonfly that would censor whatever the Chinese government required to be censored, however, protests from Google employees ended the presentation of these efforts.

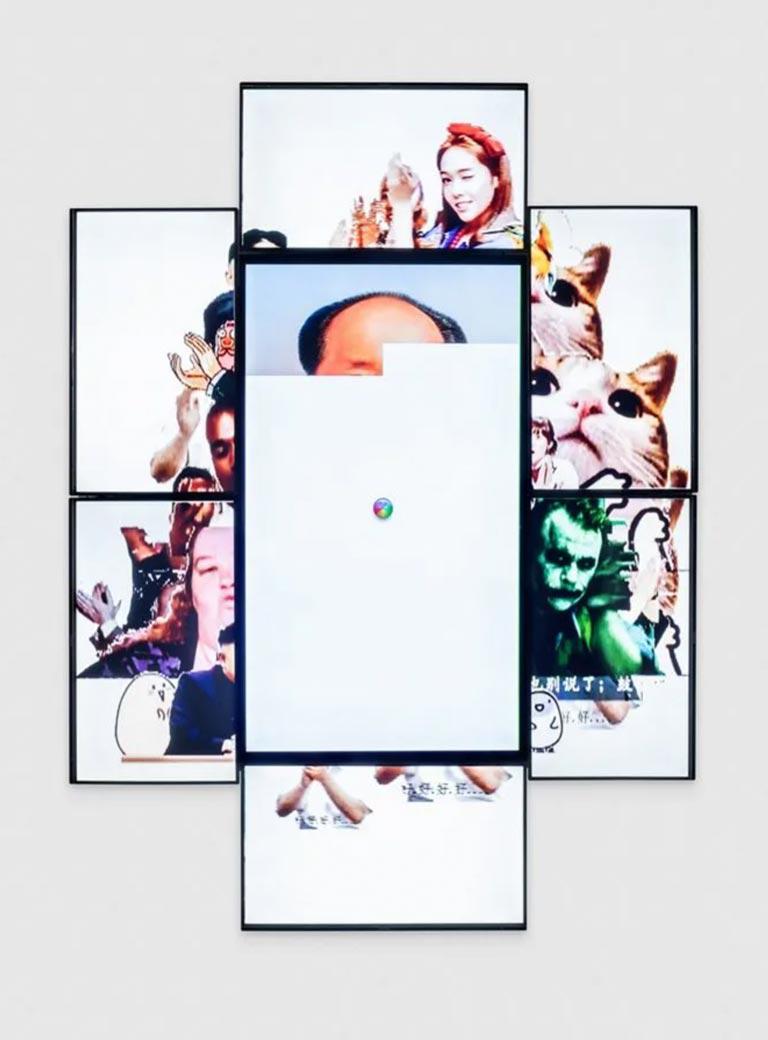

You work in different mediums including painting, video, and installation, but also use GIFs. How was this format, popular on social media, involved in your project Chinternet Plus which is a parody of the “Internet Plus” strategy introduced by the Chinese government in 2015?

Chinternet Plus was commissioned by the New Museum in New York, it was a counterfeit lifestyle ideology brand of the real Chinese Ideology–Internet Plus. It is composed of a website and multimedia installation. One of the works in Chinternet Plus- Problematic Gifs, is Mao Zedong’s image that I have purposely self-censored. It doesn’t load all the way from the top, only to his forehead. In the background, it has all the GIF-stickers from WeChat. People in China are using WeChat because it is an app combining everything. It’s Facebook, it’s Instagram, it’s Apple Pay. It’s an “All you want App”, and you don’t have to ever leave it. There are no other equivalent apps, it’s all included in WeChat, which also means that all your data is stored with one company. In WeChat you can make your own personal GIF and then send it to a friend, the twist is because it’s not a static image it can’t be censored. The most popular GIFs contain the two things that are most frequently censored in China – pornography and politics.

You raise difficult questions, but always with humor. Why is that?

I believe humor is the language of the Internet. I feel that most of the time the Internet memes from China are coming from political ideologies.

It’s really powerful to transform something that you’re not able to talk about into something that people will laugh about.

Lately, the focus of your art practice has shifted to machine learning. What inspires you about artificial intelligence?

Around 2018 I started working with a group of computer science fellows, and we have been working together continually since. That was before ChatGPT. Even these computer scientists didn’t expect AI to become so powerful, but we had an intuitive sense of its potential. Without regulation it could really take over and become destructive in a way that for example a filter bubble would not. My practice is always aware of technology. I feel that this new type of machine learning is like a math tool that everybody can use.

You collaborated with AI on a three-chapter project called Pilgrimage into Walden XII. What did you expect from AI and what did you eventually get?

Chapter one: The Honor of Shepherds was kind of at the cutting edge of high-tech. We made a game engine live simulation software that can be run on a computer. There are six shepherds made by AI that are guards in a fantasy land. At the time, no one had ever used machine learning on a game engine. Chapter two: Surplus Intelligence was possibly the first film that was directed by AI. I asked GPT-3 to study the material as the style of writing that I preferred. Over time, it started to write a loose story. It was cohesive, it had logic, but there was also a poetic kind of looseness in small chapters. After GPT-3 wrote the story, it was simulated on a game engine and directed by me according to wherever the story went. Now GPT-3 is much more powerful and can write longer stories. In that way you can actually see the film was more poetic. You might even think it was written by a human, until you for example see a storm that is made from a burrito. It makes you question your view of reality and ask whether it’s a joke or a serious story. For a project that I and computer scientists just finished we did a six-chapter graphic novel generated by GPT. This time AI studied Japanese cartoons, I used Midjourney, which is a content generating platform for imagery, so the visuals were also generated by AI.

What are you working on at the moment?

Although a lot of my work is technology-based, I always think that physical forms are really important. At the moment, I’m focusing on paintings combined with machine learning. Together with a computer scientist, I’m working on a commission from a prize of M+ Museum in Hong Kong for which I was nominated. We’re making a machine learning software that will be released in the app store but also showcased in the museum space. I am also working on paintings that have layers. First, I took an image generated randomly by AI and then commissioned trained painters to make a painting online. The painters don’t glaze their paintings anymore, because it was actually a renaissance technique, so I glazed it digitally to give the resemblance of the old oil paintings. They are really dark but also really shiny. They also look like privacy screens that people put on their phones, so you can’t see the image from an angle, you have to view it directly on to see that there’s a medieval house in the painting. There are candles, some dollars, cowboy and wizard hats. Here’s the magic. It’s beyond our understanding, like AI learning. Even the computer science guys tell me, comprehension of what is taking place is like a black void to them, because the neuro-learning of the language model of the AI is so complex, it happens, but they don’t understand how it happens! I really like the process when something digital becomes something physical.

Could you tell where and when it will be exhibited?

These paintings are going to be shown at M+ Museum in the fall of 2023. On the back of the paintings, there will be a carving on a wooden board that says “Trained”, because it’s trained AI. There will also be toys of the sort that people use to train dogs, hanging on the side and on the back of the painting.

You also have a collaboration planned with Vienna Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder. What kind of exhibition will that be?

For this exhibition, I will continue to move in the direction I described earlier. It is going to be a group of oil on canvas paintings, but with an interchange of processes between skilled human work and AI. The images were generated by trained deep learning AI on a game engine, then used as a reference image for content generating AI to “imagine” a new image, then sent to a painter specially trained in the execution of Russian Realism. I will digitally glaze the paintings depending on my intuition and feeling for each painting, so it will look completely different from the way it began. In this process, humans and AI have referenced each other, it is a combination of digital and physical interactions. Together, I will also show the live simulation software that the images were generated from at the gallery.

Many artists don’t like AI because they believe it can potentially replace art. How do you see the future of collaborating with AI?

Like the work Blind Spot, when I was searching for terms from the dictionary to Google for ten hours a day for three months, I was pushing my limits of being a human filter machine. This time, I would like to be a slave to AI. Although the age of artificial general intelligence has not come yet, the content generator of AI has already changed a lot of things from the core. Artists should be asking questions instead of regarding it as if it were the emperor’s new clothes.

Chinternet Plus-Problematic Gifs, Miao Ying, 2016, Photo credit: M+ Collection

Effect NO.6, Miao Ying, 2018

Blind Spot, Artist book, Miao Ying, 2007, Photo: Alex Lau

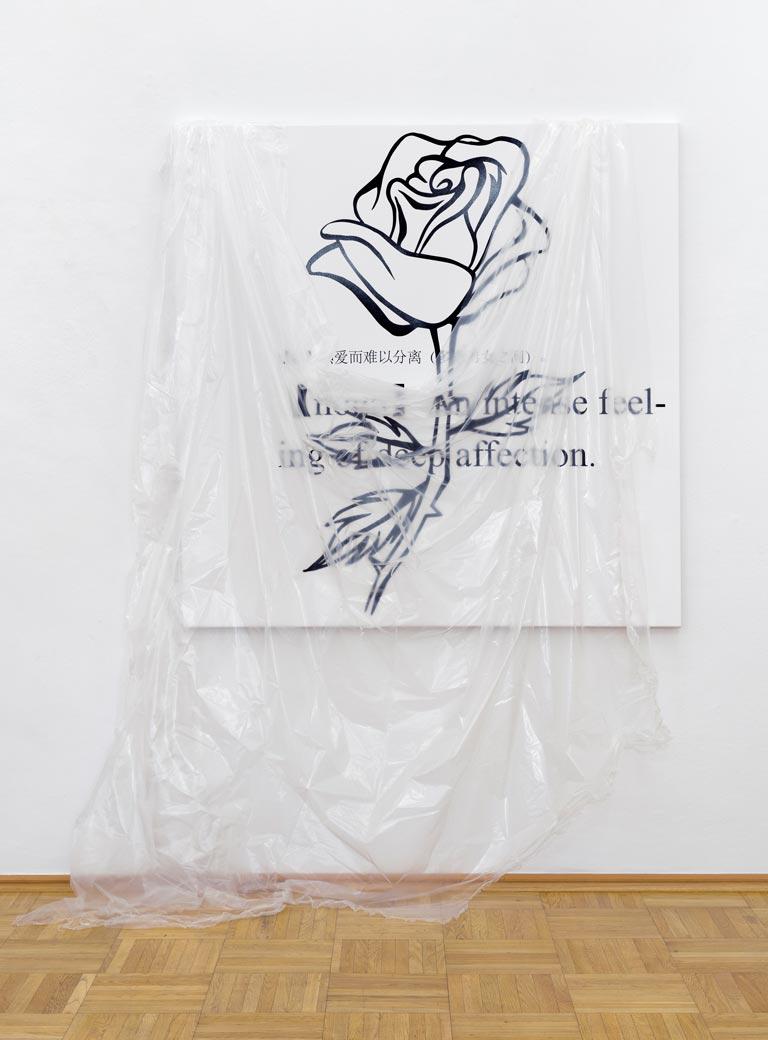

Blind Spot - Love, Words censored by Google.cn, Photo credit: Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder

Interview: Anton Isiukov

Photos: Katharina Poblotzki