As a sculptor and object artist, Michael Sailstorfer is one of the most important young voices in the German art world. Sailstorfer grew up in a family of stonemasons. His sculptures and installations interact with the environment, form spaces, and deconstruct their own materiality. The beginning of his artistic career was marked by unusual sculptures in nature. He frequently developed temporary objects that seemed incongruous in their environment. He often deals with transformative processes, temporality, and dissolution.

Michael, your career path looks quite straightforward. As a child did you already want to become an artist?

No, I didn’t think about it at the time. It didn’t actually come up until I was a teenager, when I began to find it interesting. I started making my first drawings and paintings at the age of sixteen, and then the desire became more and more solid. In my childhood I liked to build things or I had many creative ideas and then wanted to realize them. I had the advantage that my father had a craft business, more precisely a stonemasonry business. As a child I could do a lot of handicraft. And I have been doing it for as long as I can remember.

You say that your father had a stonemasonry business and was also a sculptor, what influence did he have on your artistic work and career?

My father had a traditional stonemasonry business. After he had become a master stonemason, he also studied art at the art academy, in fact he enjoyed a real art education. This was important because the fine arts have always played an important role in my family. I was allowed to attend large art exhibitions from an early age. We often visited museums, visited the Venice Biennale, the documenta in Kassel, and the Sculpture Projects in Münster. And on such occasions my father’s artist friends came with us. That was a completely natural aspect of my life, which has remained with me.

And in 1999 you began to attend the art academy in Munich, didn’t you?

Exactly, I started studying at the art academy in 1999.

And how did this decision to study art academically come about, a realization that you wanted to make art your profession?

I found it exciting. Art has always been a staple for me. The art and the museum visits, the preoccupation with it, I’ve been doing that so consciously and so intensively since I was sixteen, and I always went to the fairs alone exploring. When I was on vacation with my friends, I actually always went to the museums. That did me good, gave me peace and grounding. So the wish matured that I would deal more intensively with these topics and with myself. Of course, I knew even then that this was a decision for life. A not so easy decision, because it is difficult to make a living with it. I made a deal with my parents that I would first start studying and then, if it was not successful, I would turn to something else. But then it developed quite well.

Which artists influenced you, especially in the early phase, which artists inspired you?

This always changes with my own experience, my own feeling with which I go through the world. Taking myself back to the beginning of my studies, for example, Gordon Matta-Clark was very important at that time: Matta-Clark’s wit and slapstick humor were integral to his propensity for deconstruction of existing architecture. I always found that very important. Beuys was significant for me in his use of certain materials imbued with a certain symbolism, which became a part of his artistic language. Mike Kelley, focusing on the personal, even if it is fiction; I found it interesting that you could build a story like that around the work. But actually, a lot of things have influenced me. During this phase, I mainly sat in the library and studied artists, to a greater extent than I did any art myself.

Many artists of your generation are have increasingly taken refuge in immateriality, developing performances and installations. How did your style evolve? Why did you incline towards the opposite?

I think that was because it was so familiar to me from the beginning, because I grew up that way. It came naturally to me to think with my hands and to make things at first, I always had the feeling that this is what suited me best, and I did not try to invent or plan much, but did it the way in which it developed naturally. Nevertheless, I absolutely understand this urge toward immateriality and I struggle with it. I mean, it is probable that my work is also about dissolution and the ephemeral, for example the salt stone teeth for the Studio Berlin im Berghain. One works with these materials using a very traditional process and as such, the eventual and inevitable decay and dissolution of the object is included.

Which among your artistic works would you consider particularly important?

That is constantly changing. It is often because of how I personally develop. But the first work I did at the art academy was the work Waldputz. I worked on a piece of forest floor. I cleaned the ground, cleaned the trees. And actually, it also deals with the subject matter I mentioned earlier. You don’t add anything new, material, but you take something existing from the environment, from nature, and create a work by taking away materials. By an unnatural intervention in the natural space, a sculpture is created. Or actually even somehow a stage that stands for a certain performance of nature, namely nature itself, which reclaims space.

One of your most famous works is Time is no highway from 2005. How did the idea for this work come about?

At the time I had a scholarship at Villa Aurora in Los Angeles. And on the California highways, you’re constantly stuck in traffic jams. I am impatient and have ants in my pants and would be impatient to move as soon as possible. I wanted it to go on as quickly as possible. Then while stuck in the traffic jam I remembered something from my childhood. When I was five years old, I sanded the runners of my sled. I always sat in the basement with my parents. I wanted to go sledding, but the runners of my sled were rusty, so I got some sandpaper and sanded those runners until they were smooth again, and during the process of that sanding, the repetitive action of sanding, and the dust that resulted, it seemed to exemplify the transience of everything and the passing of time, and I was reminded of this moment while in that L.A. traffic jam. And the question was, how can I repeat this moment with the material that surrounds me in this automobile-centric city? This is how that work was created.

Was your time at Villa Aurora very formative?

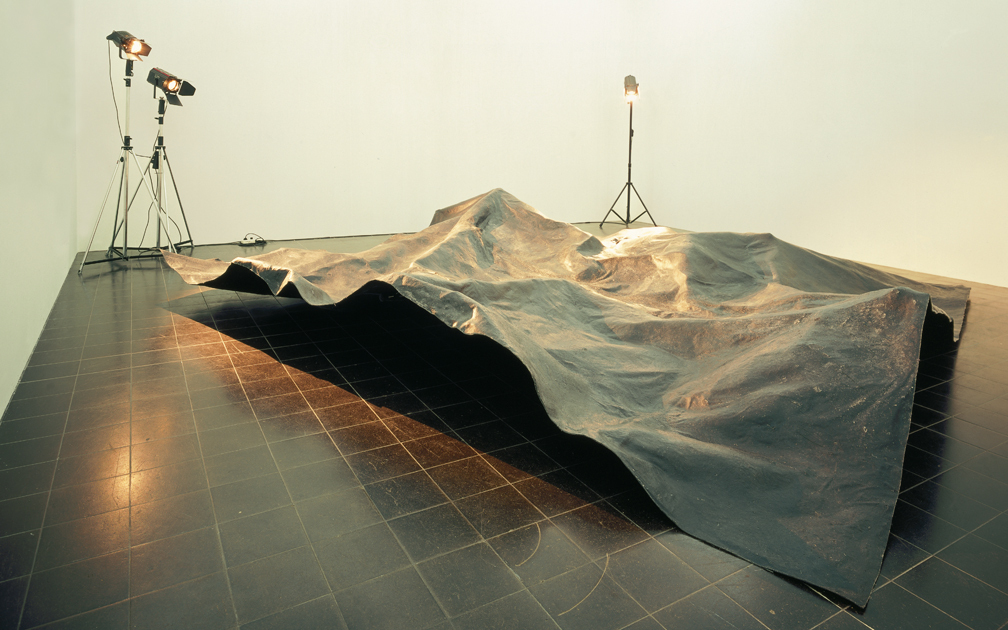

It was a very important time. I graduated from the art academy in 2005. I wanted something, I went there and then actually spent three or four months just experimenting and trying things out. I did a lot of work during that time. I built many models, sketched, wrote, and drew quite a lot. For example, I had the idea and made the plan for the work Cast of the surface of the dark side of the moon. Then I made High Visit, which is now in the Skulpturenpark in Cologne – as a model, of course. I also designed a large work for Salzburg and prepared an exhibition for Jack Hanley in Chinatown L.A. I went to Alcatraz off the coast of San Francisco. There I realized a photographic work with masks that prisoners had attempted to use as subterfuge. And I built a drum set out of a police car. It was already productive. You had the feeling that everything seemed possible, that you could do anything you wanted to. The film industry: that anything unusual is accepted as a possibility; that was inspiring.

Could you briefly explain to us how the artistic process for a work develops, how you get from an idea to a finished sculpture?

The process is never the same. There is no single thread. Most of the time it’s a preoccupation with a topic that’s on my mind. Then I look into it further, contemplate it, and accept what I’ve construed about it. I see a variety of things that surround me, and which provoke ideas. This may involve a juggling of everyday things and the fundamental vocabulary with which I am dealing. This results mostly in the creation of pictures, which I ultimately transform into sculpture.

What projects are you working on at the moment?

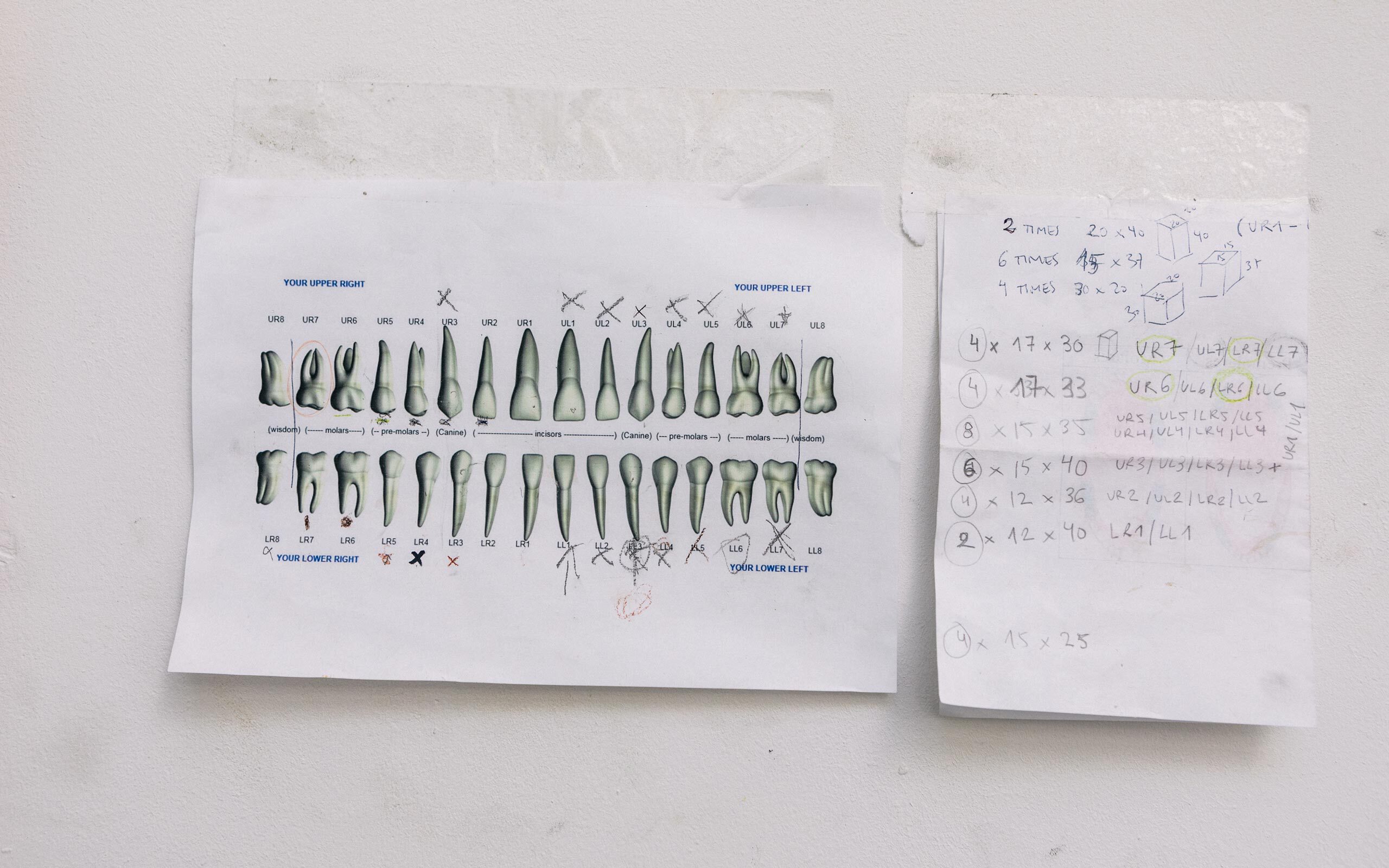

I can always talk best about the finished things, for example, the salt teeth. That was a very important work for me, which can now be seen in the exhibition Studio Berlin. It consists of thirty-two teeth, actually based on my own entire set of teeth. Each tooth is thirty to thirty-five centimeters long, and they are chiseled from rock salt, from large blocks of salt. The transformation was very important to me. Many of my works are about transformative processes, temporality, dissolution. I came to the teeth because there is so much temporality in the teeth themselves. The transformation that takes place in the body, because the teeth first grow in childhood, then the second teeth appear. The teeth are often the mirror of the body’s decay process as one grows older. Each tooth also sits on a specific meridian of the body. If the tooth does not work, certain diseases can develop. I found all those moments interesting in that they were made clear when making teeth from salt. The dissolution, the surreal and the subconscious. The dreams of teeth falling out. I found those moments good. It is exciting that the teeth are now in a club, a place that itself also stands for the moments of the subconscious: the night.

The deconstruction of time and space plays an important role for you. In some interviews you have spoken of the concept of “agency”, that causalities should be reversed in your sculptures?

You mean that there is such a contrast that is opened up? Yeah, that’s one approach. I made my first sculptures when I was a student and hadn’t had the opportunity to exhibit in a gallery yet. So I simply used nature and the external environment as a projection surface for my sculptures, a geometric surface to create a contrast to nature. And then came the first invitations for exhibitions and with them new demands. How does the sculpture assert itself in the exhibition space? I actually made works there, such as Time Is No Highway, for instance, in which the sculpture has a certain life of its own and spreads, for example, through the way it smells. In other words: a small sculpture that can fill a large space through its smell. Basically, you always have to think about the space where the work is shown. And always open up a contrast where the sculpture can assert itself.

Especially in your initial phase, you put nature very much at the center of your work, for example in works such as Main Route and Byways, or Living with Transport Connections. What messages did you want to convey?

I can’t say in a generalized way. At that early time, I was also very much concerned with the question of where one settles down, where one locates oneself. It was about creating your own place. That was the reason why I made Living with Transport Connections. Those bus waiting structures serve as shelters, but at the same time, one doesn’t want to be there permanently. You are connected to a city by the bus line. Actually, I was interested in the interaction between urbanity and the rural, that where you are, you never really feel comfortable, you always dream of merging into the other. That is what the work is all about. Main Route and Byways were created much later. In 2010, I was in an artistic crisis. I didn’t know exactly whether I was going forward or backward. But relatively speaking I still had plenty of exhibitions at that time. Then I asked myself, what are you doing now? I now reflect exactly on that, the fork in the road where I find myself.

You once had an artistic crisis?

Over and over again! I think that’s simply part of it. There are always gaps where you stand between two groups of works, where you think that I should actually take a deep breath, I need and take a little time for myself. I need input. I often have the basic feeling for the next work, but I need distance to gain clarity. Main Route and Byways stand for this transition. I got into a new group of works, but I had to exhale to find them. The work was a projection of this situation.

Which exhibitions have meant the most to you, shaped you and brought you forward?

The shows I did at KÖNIG. This is my home base. I always want to show the biggest, most innovative and most important things there. For example, Hitzefrei was an extremely important show for me, because there I saw what is sculpturally possible. The exhibitions at KÖNIG are always an experiment where something new could happen. But early exhibitions were also decisive. One of my first exhibitions was in the Lenbachhaus in Munich in 2002, an outdoor sculpture entitled And Yet It Moves. At the time I received the request, I was in my sixth semester at the academy. The Lenbachhaus simply had a gap. That was a big chance, the start of my career, so to speak. It was also during this time that I came into contact with Johann KÖNIG.

What do you wish for your artistic future? Which projects are in the pipeline?

There are just a few projects. I am doing another exhibition in January 2021 in Copenhagen. There is a group of new works. I am preparing a show in Mexico City for April. But what always fascinates me the most is something completely different: when you deal with a topic that is important to you and then you have the image for a new work in your head. When you realize that something works artistically. This conscious feeling for a good new thing that is created in the studio is fantastic.

Cast of the surface of the dark side of the moon, 2005, fiberglass, theatre lamps, 100,00 × 500,00 × 500,00 cm

48, 2020, Salt, 13 × 24 × 15 cm, Photo: Roman März

Zeit ist keine Autobahn - Frankfurt, 2008, tyre, iron, electric motor, 80,00 × 65,00 × 95,00 cm

Waldputz, 2000, cibachrome, framed, 30 × 45 cm

Interview: Kevin Hanschke

Photos: Nora Heinisch

Links: