Conceptual artist Monica Bonvicini is one of the most exciting artists of our time. With her multi-layered works she examines the interplay of power relations, gender roles and architecture. Her works reflect the meaning of art production under socially relevant aspects as well as the performativity of language. We spoke with her about the dissolution of patriarchal structures in art history, about clichés that she had wanted to eradicate for quite some time, and about the necessity of change in life.

Monica, how did it all start? When did you know that you had to make art?

After high school I was not sure what to study: sociology, political science, or art. I took a year off and went to Hanover to learn German; I really wanted to read Nietzsche in the original. I looked and applied to a few art colleges including Berlin. I could have had a place in Venice, where I would have studied with Emilio Vedova; I wanted to become a painter at that time. I was interested in the dichotomy between economy and socio-political issues, and thought I could work on these issues through art.

Why did you decide against Vedova and Venice?

On the one hand I was young and didn’t want to study in Italy, on the other hand I figured Venice would simply be too beautiful to study there. At the time, I found Berlin so exciting, because it was so ugly, so bleak, the exact opposite of Venice, it wasn’t beautiful, no pluses, it was rough. That was exciting to me. I thought, in this city one would be able to concentrate well on the essential.

Even in your first works such as Wallfuckin’ (1995), you had broken with the idea of conventional space, what fascinates you so within architecture – and its artistic changes?

It is difficult to imagine something that is not a space. We live in an apartment and we work in an office, or at the cash register in the supermarket, or in a law firm – no matter where – one is always surrounded by spaces. When one exhibits in an art gallery, in an art association, or a museum, one has to deal with spaces. Even if one works with the public space, there are boundaries. Urbanism is also a form of built space. One can’t think of the “I” without thinking of spaces, in which the “I” develops and takes place.

How has your personal relationship to space and architecture changed over the years?

My feelings about spaces have remained the same, regardless of whether or not I feel comfortable with that. My exploration of spaces has become more conceptual and so has the investigation of spaces. I still circle around the same topics as I used to, because that is where my interests lie. Architecture and spaces have changed in the past thirty years; there are many spaces that have been added – virtual spaces for example.

Do virtual spaces and artificial intelligence play a role for you?

I find artificial intelligence very interesting, because this development is just coming into being, one can experiment a lot with it. I have followed it for years, but I haven’t done a project with it. I haven’t come across anything yet that has truly excited me, especially something that could truly evoke a collective experience and perception, which is really very important to me. When I work in an installative context in terms of space, visitors have the opportunity to look at and perceive, to feel something either together or separately that is simultaneously there for everyone. Dealing with reality and materiality is very important to me.

The collective experience is also something you play with in your current exhibition I Cannot Hide My Anger at Belvedere 21 in Vienna. Do you think that the experience is always the same for the individual? Or does it make a difference if someone already knows a lot or even nothing about you and your art?

What someone feels is certainly always different and I can’t anticipate who will see my exhibition, and whether or not the audience already knows about my work. The more one knows the more one understands. My works, especially the installations, like those shown at the Belvedere, enable an understanding that is first accessed through physical perception. The museum itself, the architecture, the institution’s history can help to understand works. I work with that and try to be as clear as I can so that what I mean becomes clear.

Is it important to you what viewers think about your exhibitions?

I am interested in building a discourse about issues and to provoke reactions. The title of the exhibition I Cannot Hide My Anger for example is a quote from the American writer and feminist Audre Lorde that goes even further. I think it fits today’s gender, feminism, and LGBT as well as political issues. The exhibition can be seen in Austria. We are living more and more in a Europe that is oriented toward the political right. I have strongly concentrated on the architecture and almost “reacted”, because I know the building so well. I wanted to make the center of the surface inaccessible and at the same time make the periphery the space in which everything takes place. The center is now excluded. This has certainly a very strong performative aspect, this large installation. You walk along all four walls of the installation trying to find the entrance. One is always looking for the surprise or expects that something is going to happen. But while one is looking, one is already there.

Are you a political artist?

I understand myself as a political person. As far as institutional criticism is concerned, I really do want to strike a political nerve. The answer therefore is: yes, certainly against the institution.

Are you also against people like Trump?

Yes! Also against Austria! The Upper Belvedere is a beautiful cream cake where everything seems to be wonderful. But the barbed wire in my installation is not that far away from Vienna. I have been working with the cowboy figure, or with the Marlboro advertisement for a long time. In 1993, I made my diploma work using four large Marlboro posters. The Museum of Modern Art owns several collages which I created in 1995 with the Marlboro advertising, and in 2000, I integrated the Marlboro Man in the publication EternMale, a publication that dealt with the male domestication of Playboy magazine, and I think in 2003, I presented the Marlboro Man in a communist pose in a poster event at the Secession. Unfortunately, it is no longer funny when one looks at what is happening in the Plains of Texas.

Do you see art as a mirror of society?

I think art is always a mirror of society. I expect that from art. What else is it supposed to be? If it’s not art then it is décor. And when it is décor it is also an aesthetic, which is a product, an expression of society. I can’t see it any other way.

Some people feel provoked or scared by your work, for example by the encounter with the swinging big whip in Breathing (2017), which could be seen at the Art Basel this year. Others remain standing meditatively in front of it. Can you understand such reactions to your art?

I don’t want to scare with my art. On the contrary, I want to do the opposite. I want my art to inspire ideas of which one would otherwise not have thought. One should wake up a bit through what one sees. I am often very surprised by people’s reactions. I also enjoy watching these reactions. There are also people who have no inhibitions at all with Breathing, for example, and get much too close.

Can you let go of your works when they get exhibited?

When a work is exhibited, it is somehow no longer mine. It is not difficult for me to let go. There are directors who no longer go to the cinema because they can no longer watch their films. I feel the same way. I mean – I always like to look at my work again. Ad an artist you are very close to your work while you think about it, do it, build it… But at some point the works have to go into the world where they belong.

Because of your range of different styles and your strong interest in various materials, objects, and substances art historians often compare you to famous male artists like Bruce Naumann. Does that annoy you?

It could be worse than to be compared to Bruce Naumann (laughs). I think art history is still strongly dominated by male figures. Right now, the subject gets a lot of attention although people know they generally shouldn’t do that any longer, preferably not for the next twenty or one hundred years. I can’t say that it annoys me because I know it’s just the way it is. Usually it concerns people who are either men or not well versed in art history. There are indeed artistic references between Bruce Naumann and me, but it is not nice to be constantly confronted with these father or male figures. At some point you have to kill the fathers, and I have already been doing that for a long time. The work takes this space that becomes free as a result.

Is attacking patriarchal structures the famous “red thread” running through your work?

Yes, I believe so. I am still interested in that. Although many things have already changed, much has remained the same. If I were a man, my work would probably be understood differently, even today a different kind of work is still expected from women artists. I enjoy attacking a certain kind of art history and messing it up a bit. I also like to work with quotations, e.g., from literature.

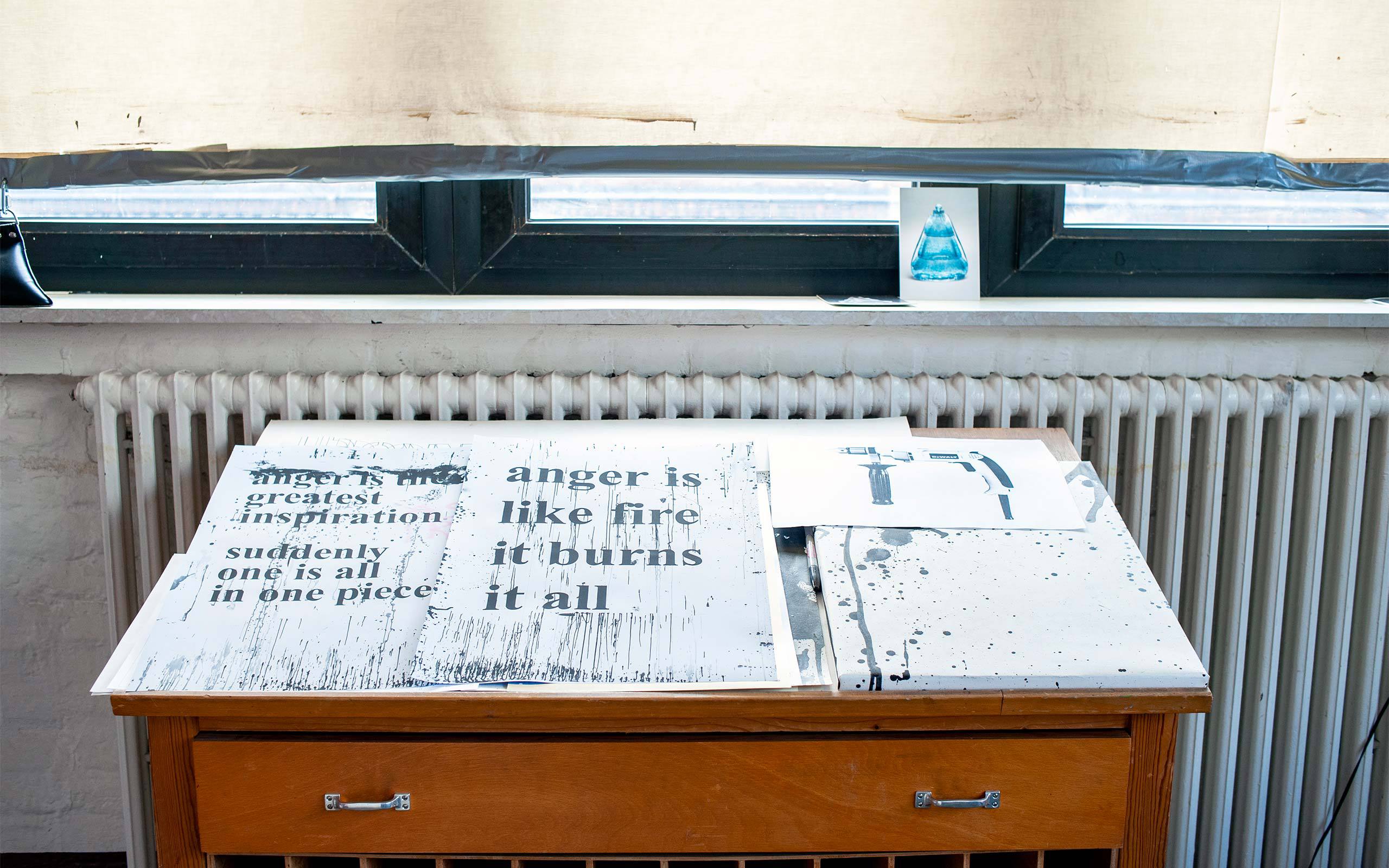

Literary references are important aspects of your artistic work. Why do you love working with language?

If I hadn’t become an artist, I would have become a writer. I believe that language opens spaces as much as do sculpture or installations. For me, in any case, much more than cinema. When I read a good book, I can well imagine the spaces in which the action takes place. With Thomas Bernhard, I can even small the scent of spaces, that’s how well they are described. It’s the same with poetry where with incredibly few words an emotional space can be created. I love that very much. Language has no personal weight. I am interested in the space that can be created by language, by making it three-dimensional.

Are there misunderstandings or prejudices about your work with which you continually struggle and would like to do away with?

I find it boring that many people still assume that what an artist does is the person him- or herself. That is so old-fashioned. Many people think I am an SM addict and that my work is all about that. It is always read with that aspect in mind. I also have to say that my first works, especially Wallfuckin’, were interpreted as feminist works and put in a drawer, and that wasn't very “in” at the time. It was not “not being in” that really bothered me but the drawer it was put into. If my art is reduced to SM themes, one simply does not do it justice. My works were not created in a SM-cellar, but rather in a much more complex context, the entire world is reflected in my work. What some people also fail to understand is that my work usually has a lot to do with history or with the construction of sexual identity. I am interested in how to get there and what it means historically.

What roles do change and renewal play in your artistic career compared to recognition and focusing on specific themes? Is there now a kind of “brand Monica Bonvicini”?

If there is a “brand”, then others ascribed it to me. It is incredibly difficult to choose from all of the possibilities; it is a great responsibility to me and to others, and at the same time a great freedom. I want to exercise this freedom by not only making videos or installations with light and so on. In the past 25 years I have surely developed a certain aesthetic, which I think is clearly recognizable. For me, if a theme has been dealt with, then it is finished and I no longer have the need to reexamine it. And that’s what I often think when it’s exactly what it has to be – why make variations? Don’t all artists want to do that, to make everything new?

Well, at the beginning of a career, gallery owners in particular often want to see work that can be easily sold, which can immediately be recognized as that of a specific artist …

… That’s true, but I want to say to young artists: When I was still studying at the UdK, many thought that I was a very talented painter. Then I stopped painting. There were people who saw it as an affront and didn’t talk to me for years. You shouldn’t let that mislead you. You have to change.

And now think freely and look at the history of art: with whom would you like to make an exhibition and why?

With Lee Lozano and Cady Noland. I would have loved to get to know lee Lozano. I think one needs someone who can be so radical, a friend, and a colleague like her. And regarding Cady Noland I don’t have to say anything, it is self-evident. It would simply be good with us; we would have fun, and the audience as well!

Monica Bonvicini, Breathing, 2017, Photo: Andrea Rossetti/Courtesy the artist and Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

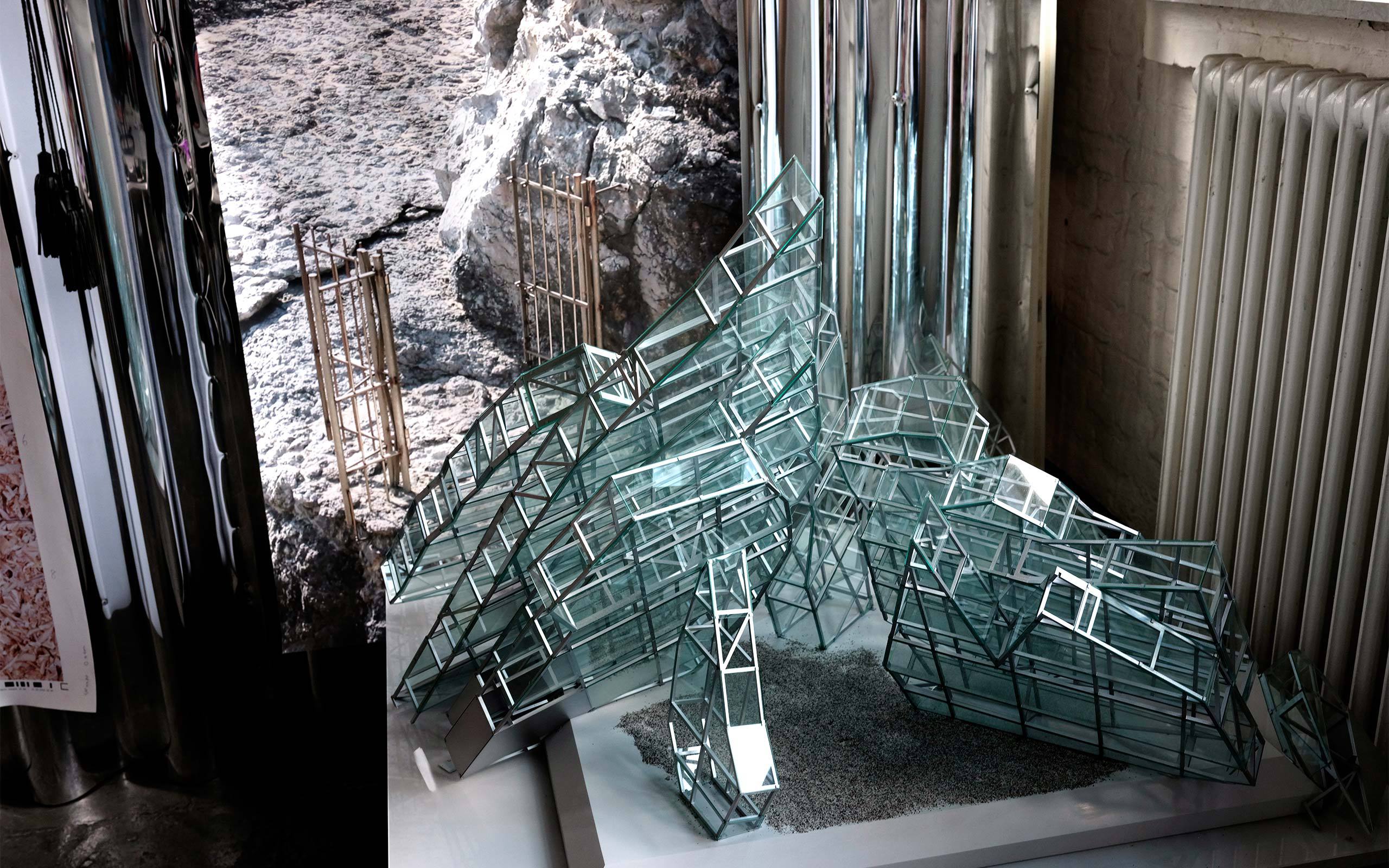

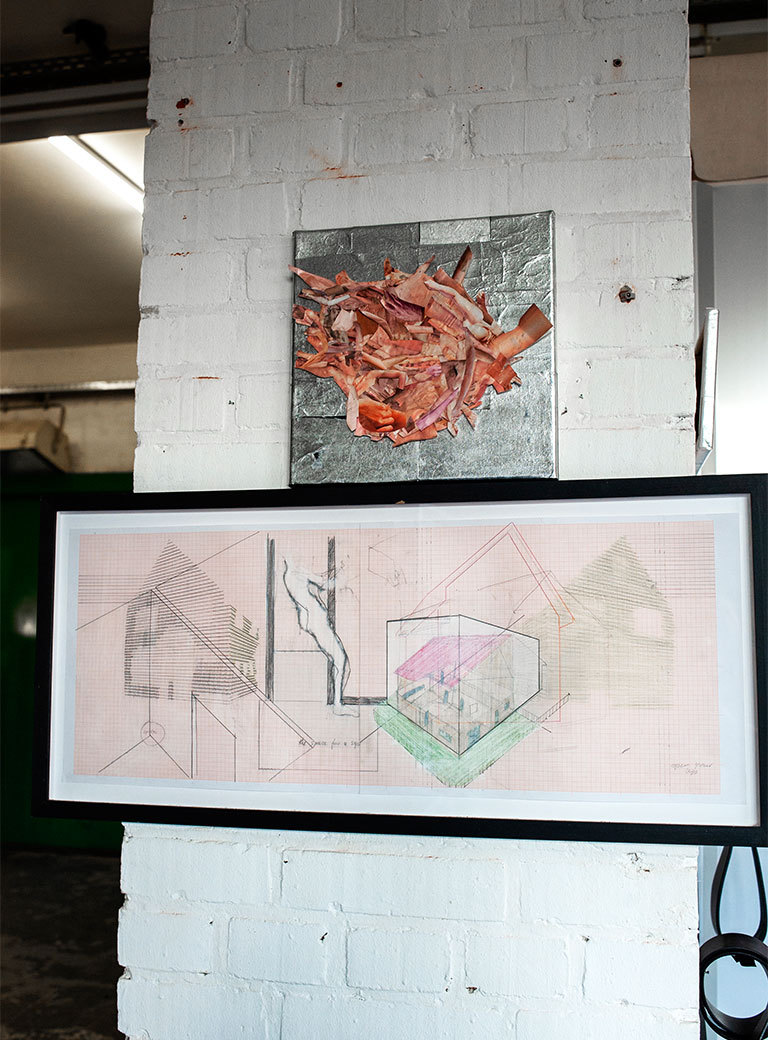

Exhibition Views Monica Bonvicini: I Cannot Hide My Anger, Belvedere 21, Vienna, 2019; Photo: Belvedere 21/Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

Exhibition Views Monica Bonvicini: I Cannot Hide My Anger, Belvedere 21, Vienna, 2019; Photo: Belvedere 21/Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

Monica Bonvicini, Marlboro Man, 2019, Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

Interview: Dr. Sylvia Metz

Photos: Franziska Rieder