Markus Muntean and Adi Rosenblum have been an artist duo since 1992. As conceptual artists, they bring together motifs from art history and popular culture in their drawings, paintings, performances, and installations. Here they continually play with lifestyles of a youthful society, one that never wants to grow old. By appropriating and interweaving images from different sources, they critically reflect, especially with figurative painting, a (media) world of influenceability.

Adi, Markus, how did you get into art?

Adi: I have been painting since I was a child and was always fascinated by art ... So it was a romantic idea from the beginning to become a painter, inspired by masters like Caravaggio. I grew up in Israel and there were very few originals to see in museums, there weren’t that many travelling exhibitions then either, but being able to see them was very important to me. From the beginning, figurative painting was in the foreground for me. There were times when I tried something else, but in the end I decided on figurative painting. Figurative painting creates a specific meta-level for me – the painted view can be more emotionally moving and mysterious than any real situation.

Markus: For me, there are two main strands; on the one hand, the realization very early on of not wanting to fulfill social expectations and seeing oneself as an outsider in a positive sense, and on the other hand, an early developed interest in artistic practice. This is actually quite simple and almost classical. There was no epiphany, it was more like Adi’s, the encounter with images.

You studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and joined forces as an artist duo in 1992. How did that come about?

M: We shared a studio and there was this period of working side by side, where everyone produced works for themselves. But then it slowly grew together organically, so that one intervened in the other’s work or that there were overlaps. It was largely a case of luck, although there were discussions on the approach to deciding upon the compositions, but apart from that there was no disagreement, and that’s what made the collaboration possible in the first place.

A: When we met, it was also the great love and we were interested in the same thing and had common goals.

When people talk about you, they often say “one work two artists”, “four-handed painting” or “double authorship”. What is your position on this?

A: We studied at the same time, in the late 80s, and at that time there was this cult of painter princes and we thought it was ridiculous. In the 90s, art was dominated by conceptual approaches and painting had rather taken a back seat, but we still continued our painterly practice. And then we felt that if we practically invent a persona that is in the foreground, it will allow us to separate ourselves from this “cult of genius”.

M: I’m amazed at the tenacity of these artists’ work, such as the spontaneity, the pouring over the canvas. This new persona is an evolved structure for us and also fits into our concept, like the questioning of the contemporary ego structure, what is the ego anyway? Because we paint portraits, but are they really portraits ... It’s a game with identities and we have developed a signature style that is practiced by two people.

Does that mean there was never any thought of a loss of identity for you?

A: Not really, otherwise we couldn’t have done it. The bottom line is that they are choices and I even believe that ego is an impediment to good art and that collaboration helps you get away from that ego trip quickly and you focus more on what is really essential. Each of us knows where our strength lies, which means it’s okay to admit that the other person is better at certain things, and that’s a good thing. We know our capacities and we are confident enough. We have never felt that we have to realize ourselves in the sense of: This is ME. We have never been interested in that. As Markus said, it’s partly a romantic idea of what the artist is or does. You create this persona, even if you work alone, and we do it together.

M: That’s right, there was never much doubt. Of course there is a margin, but there was never a loss of identity. Of course there is an identity, but it’s composed of many layers and that’s what makes it interesting. We’ve created this persona, and so a signature, an individual style, which means there’s the two of us, so to speak, and then there’s this style that exists and that also has an identity. It’s more like there’s an identity that comes with it.

This Is Not an Exit , 2018, MAC Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, A Coruña, Spain

People are at the center of your work, but it is said that you only show perfect and beautiful people. Isn’t there rather a criticism of our society behind that?

A: That is definitely critical. We reflect our collective visual self-perception. But this supposed similitude is only one level, on the other hand there is something that painting can do, it evokes a break and brings a depth. That’s why we use painting and not photography. So the figures radiate a melancholy and forlornness. The principle of ambiguity is important here. What we’ve been trying to portray since the earliest times is the feeling that the whole society is becoming more infantile. Our whole culture is becoming an adolescent culture. It’s interesting how people on Instagram are jumping in front of the camera like little kids and doing stupid things ... We live in a society of perpetual adolescents.

M: But also if you look at the history of art, almost all the figures that are painted are young and pretty, it’s always been like that, we didn’t invent this selection of beautiful people, we perform it in a critical form.

What exactly does that mean for your art, to pick up on and address this perpetual youthfulness?

M: This aspect of the repertoire also serves to draw a line of demarcation between our work and any form of “genre painting”. Therefore, the backgrounds we use are so important to us. We have our repertoire of urban and landscape elements, but they are also individual to us and at the same time they’re not. Also with the figures, they are portraits, individuals are clearly identifiable, with individual traits, but also certain stylizations. The youth is to be understood in this direction and not an attempt to appropriate a youth culture, but to find a contemporary formulation of figurative painting. We see ourselves as conceptual artists. That is why we use contemporary visual material that provides this form of smoothed youthfulness. However, we try to produce an opposing quality in the material itself and introduce motifs of transience and “memento mori”. As Paul Celan said: You cannot reach across time, you can only reach through it.

A: In our post-religious and turbo-capitalist society, transience is almost wiped away, as if it goes on forever. The ageless and youthful, as in the images on social media, even through the use of filters, is like a shield or armor against impermanence, as if one were no longer dying. You're not really living and you’re not really dying, and that’s so the present zeitgeist. It is a basic mood that is conveyed and that’s the feeling that we want to take up and convey further in our art. In this contemporary visual communication, the perfection of the body and the smooth surface are in the foreground; but all the more one seals the inside – apparently one no longer needs to be afraid of death.

M: Right. And that’s the contemporary material, that’s what’s omnipresent and overwhelmingly strong, the smoothed-out human being, and we use the material partly in this counter-rotation, i.e. not that we’re running after an ideal there, but it’s a play with ambiguities. There’s a certain realism, but at the same time you consciously reduce the spectrum within that.

You express your themes, such as that of transience, primarily through figurative painting. How do you do it, what approach do you follow?

A: The discourse on figurative painting is unfortunately very limited. Only the “what” is discussed, but the “how”, which is inextricably linked to it, is hardly addressed; at best, it is mentioned as a secondary phenomenon.

M: That’s true, and unfortunately, it is discussed the least. The transformative power of figurative painting is totally underestimated, unfortunately. It is important to us what direction to take in the activity, what to use, what style, the gesture ... Painting is our obsession.

A: We did a lot of experiments and developed our stroke together. About seven years ago, we developed our own form of mixed media, combining oil and pastel chalk in a novel way. The powder character of the chalk enhances the reflective power of light and acquires new intensities of illuminative effect.

M: And there is this tendency to say that figurative painting is not needed because of photography, which is absurd. We definitely see ourselves as painters who also work with other media, such as film, or we proceed installatively, and for us that is a kind of extension of painting. As conceptual painters, we are concerned with an overall staging.

How can we imagine your working process?

A: We are almost always working, researching and creating the image compositions on the computer is as much a part of the working process as the actual painting itself. We also deal with the many time phenomena on social media, how people represent and see themselves. These various streams and appropriated images are sources for image compositions. But we also do our own photo sessions with models in the studio and create our own staging. When we decide to paint a picture, we have a framework idea of the scenario, an assemblage of different images.

M: Ideally, it’s mixed and we combine our studio shots with found footage, because certain things are almost impossible to recreate. We then make one or two sketches on the computer and project these rough outlines onto the canvas. And then we start painting together, meaning one starts and the other joins in. There are four or five phases and we take turns. So we tend to work in shifts.

A: Exactly, or one mixes the color and the other applies it and vice versa.

Untitled („Each word is a chemistry...“), 2018,Pastel chalks, oil /canvas, 212 x 286 cm

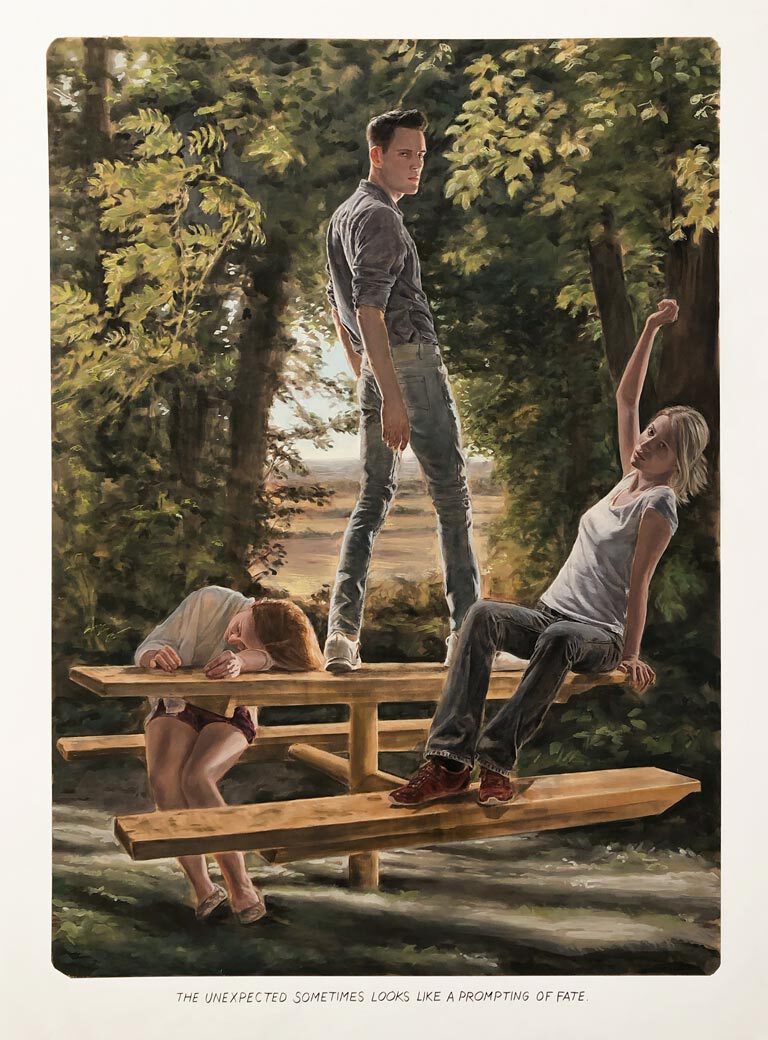

Untitled („The unexpected sometimes...“), 2022, Pastel chalks, oil /canvas, 193 x 141 cm

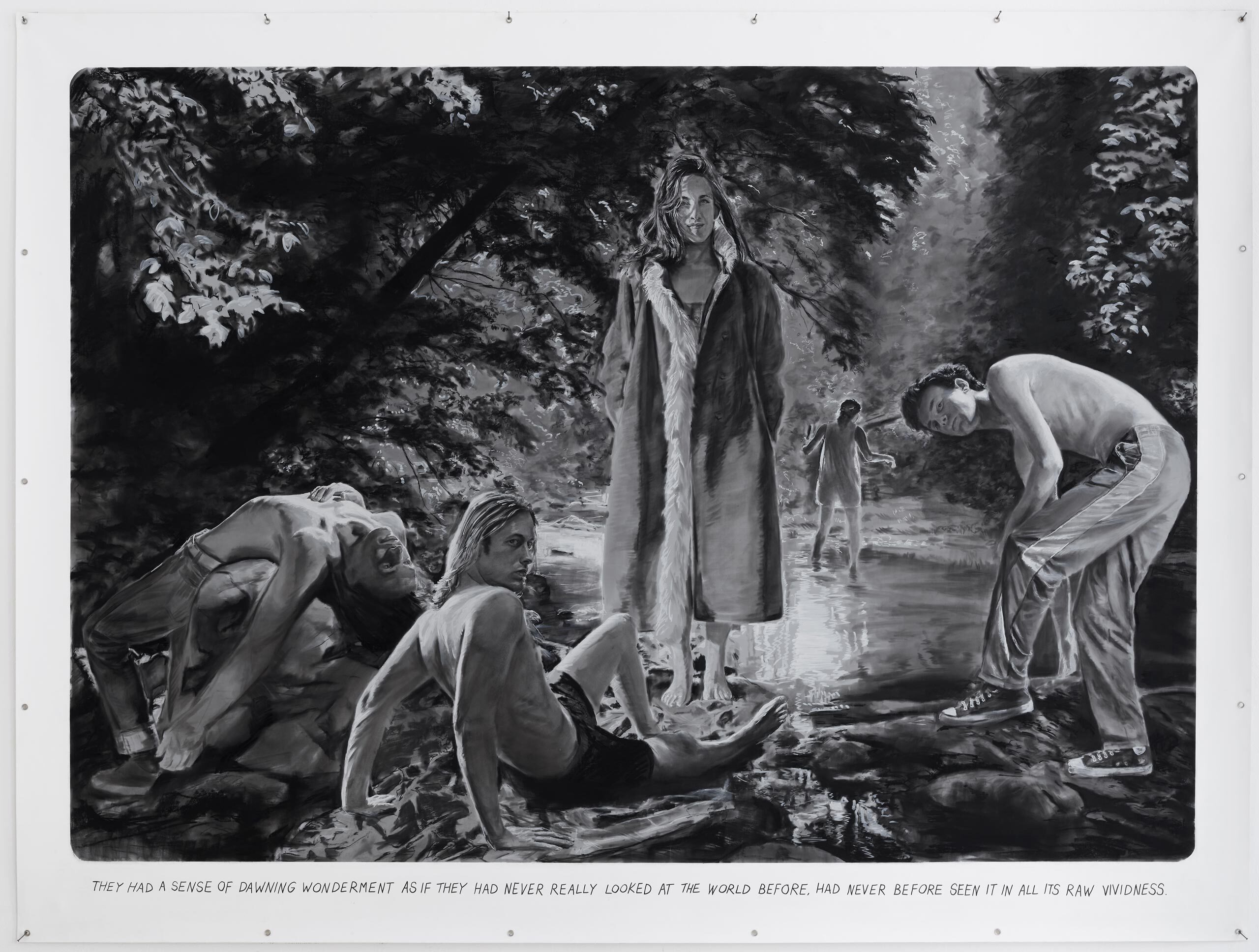

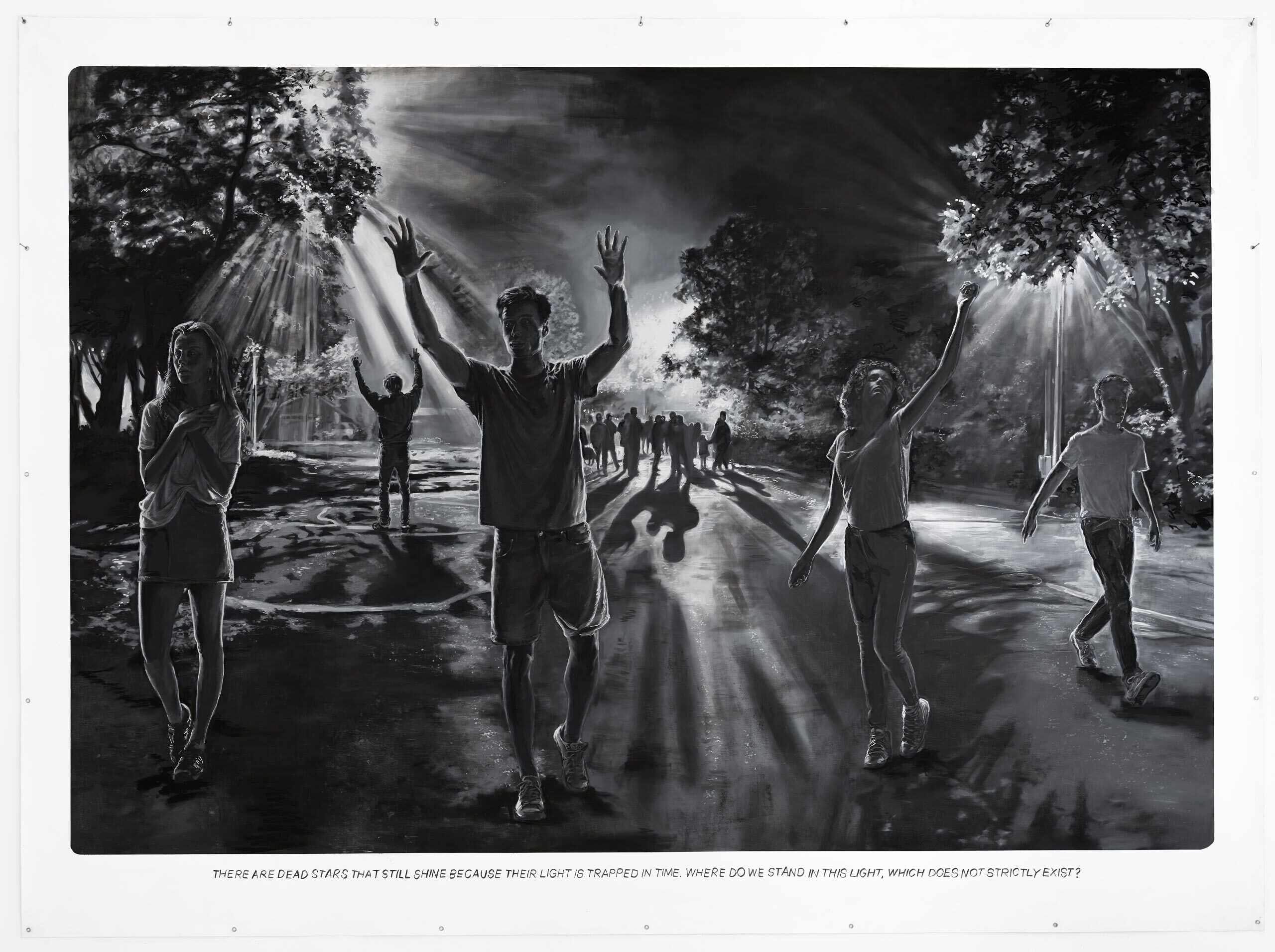

Your paintings don’t have titles, but there are text fragments in the paintings. What meaning do these have?

M: The text is neither a title nor an explanation of the picture context. It forms its own level and is intended to open up a further field of connotations.

A: We archive a great many sentences from books and films, sentences that interest us. The sentences are meant to convey a certain atmosphere, a specific “flavor” that is situated between poetic observations and general aphoristic wisdom about life.

In general terms, what does art mean to you? What should it achieve?

A: In our post-metaphysical age, art represents one of the last meta-levels that allows a salutary distance from the immediate contexts of life.

M: Ultimately, art serves to make life more bearable. Ultimately, art is about, because otherwise it is really pointless, moving people and triggering emotions in a justifiable contemporary form and in this sense enriching life.

Staying with consuming art, what is it like when your work leaves the studio? Do you have expectations?

A: It would be bad for us if we didn’t have the opportunity to exhibit. But in no case do we want to be admired. That is not important to us. In fact, when we finish a painting, it’s gone from us ...

M: It pleases me when I see a painting again after ten years, but it’s not that I'm so interested in the fate of the works. In the end, you make art for yourself, and fortunately, as in our case, it appeals to people.

Untitled („We don’t get to…), 2015, Pastel chalks, acrylic / canvas, 285 × 405 cm

Untitled (There are dead stars…), 2018, Pastel chalks, acrylic / canvas, 280 × 380 cm

In retrospect, do you think earlier work of yours is looked at differently today?

A: Definitely. I think that we have really anticipated certain social developments in our work.

M: One of the main issues has always been that the characters are so isolated, each standing alone, they don’t communicate and seem lost.... And now? Today you sit at a table with friends and everyone has their smartphone in their hand. Now this question doesn’t come up at all. The question, and the accusation, have disappeared.

A: Much of the negative criticism that came our way at the time implied that we were formulating a fleeting zeitgeist phenomenon with an imminent expiration date. In retrospect, it turned out that we were dealing with lasting mass phenomena that are still shaping our present.

What are you currently working on, what can we look forward to?

A: We are always in a process of creation and trying out things like dealing with meta-humans, so virtual computer-generated figurations, but that is still a very new idea.

M: We had constantly emphasized that portrait commissions are not compatible with our concept. But now we have developed an approach that allows us to do just that: it is based on the concept of an extended “selfie material” that the client provides us with. We then incorporate this into our painterly world and the resulting images fit seamlessly into our other group compositions.

A: And we are looking at the exhibition at the Albertina, Hauenschild Ritter – Muntean/Rosenblum, which opens in October. We’re excited about that, and hopefully it will be an interesting show with a good mix of paintings and drawings from different periods. There will be works from the collection, international loans and also completely new works.

A New Age: The Spiritual in Art, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2019

Glaube, Liebe , Hoffnung, Kunsthaus Graz, 2018

Interview: Marieluise Röttger

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov