The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Everyday objects are more than meets the eye to Danish artist Nina Beier. She showcases innocuous objects such as china, wigs, and pointedly massive bronze statues as more than just materia, but as reproductions of values and views – or as “representations of a world order,” as the artist puts it.

Nina, we could call you a professional treasure hunter on eBay. What part does it play in your work?

I have a love-hate relationship with eBay. I throw so many hours into the search for my objects. I end up buying all kinds of stuff from people because I need to get my hands on objects I am interested in order to find out what they are capable of doing for me. At one point I thought I needed to get a lot of reading glasses, then for a while I bought old lace curtains, then there was the time when I collected pastel plastic toy castles. Now, I have 25 pairs of reading glasses. eBay is a dangerous place.

Everyday objects are at the center of your art. You search and find, transforming objects into mirrors of the world around them. What are you looking for in an object?

I tend to get attracted to things that carry some sort of a problematic tension. This state often appears at the time when the value of an object is being renegotiated. A clear example of this are the hand-rolled cigars I worked with – the cigar is an object that carries some heavy baggage: global trade history, notions of wealth, power, and patriarchy. When you look at this object, the space that unfolds is different today than it was just 10 or 20 years ago. There is something about the transitional moment in an object’s status, when we can all of a sudden see it for what it is, when it becomes a vehicle for its own history.

How do you know what object to pick?

My process usually springs from a curiosity about a specific family of objects, and then I start acquiring varieties of that object. Lately, I’ve been buying marble eggs. Objects that have been produced collectively over generations, and often also across continents, this is something that is reoccurring in my practice. These are things that exist in many iterations that have gone through a process of mutating and changing shape through the different interpretations along the way. It is very rare that I’m working with an object that is made by a specific designer or where the intention of the object is one-dimensional.

Does this go back to the objects being universal?

I try to make the objects speak for themselves, by finding openings in them – either by making meetings between them or by unfolding them or cracking them open in a way that makes them speak for themselves. The objects can lay out their own history in front of us, and then we can get to sense what they mean. For me, it is really important to interact with the object to find this place where it comes to life in front of us. When we can see it in its multiplicity.

What is this interaction like?

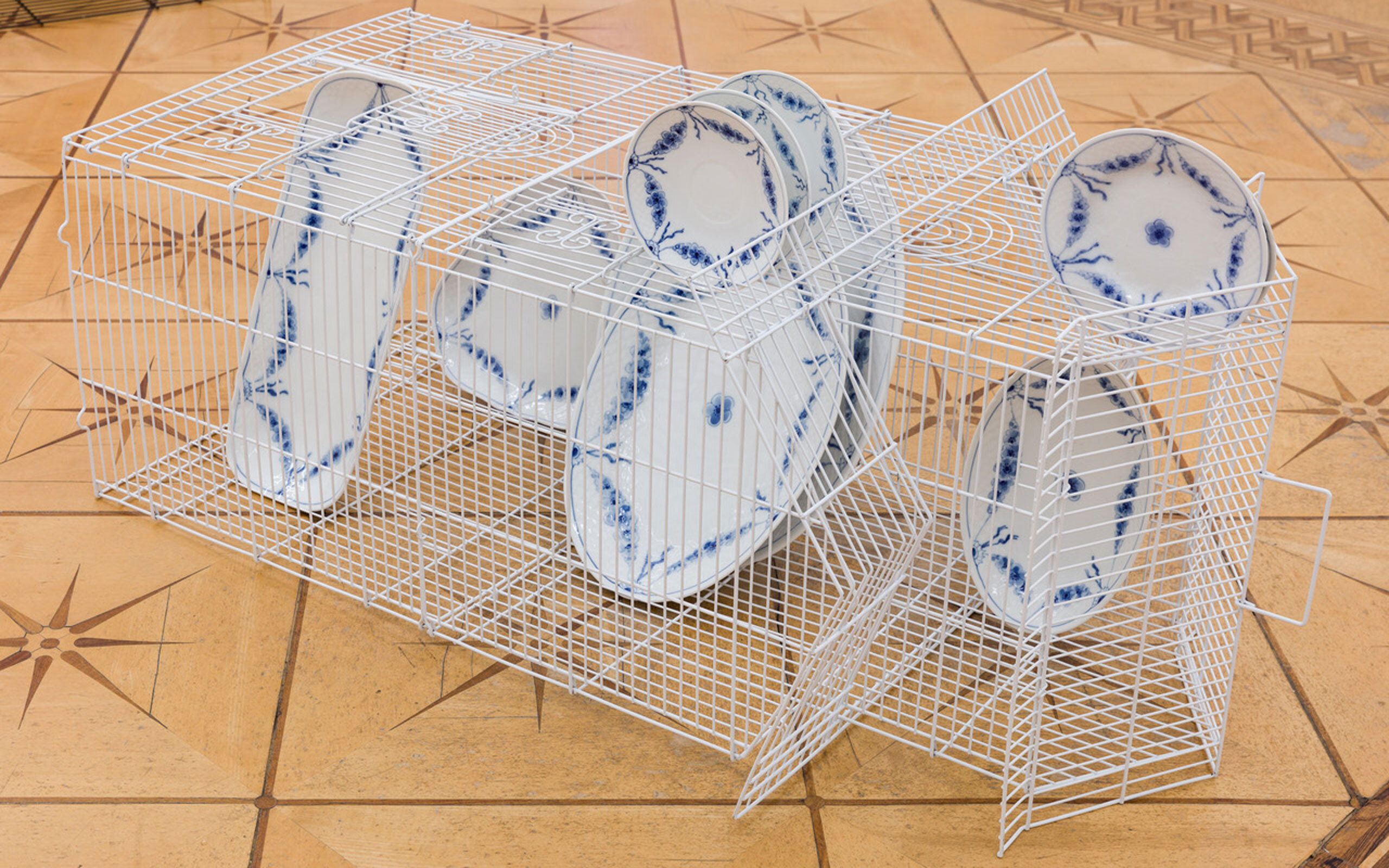

At my studio, I have different meetings of the collections I make. Sometimes, the dialogue happens naturally between two things, while other times I’ll bring in an object to try to unlock the other. In one case, I just collected a lot of birdcages and I had them at the studio for ages. I started collecting the cages because I got interested in how birdcage designs absurdly tend to replicate specific human architectures. However, what I intended to do with them just didn’t work, so they were standing around for years. Eventually, I put a plate in one of them to dry. They were just there at the studio waiting to be employed.

What happened then?

The cages were finally paired with a classic Danish dinnerware set called Empire. My partner inherited a set from his grandmother and I was instantly intrigued by its name. The story is that Chinese porcelain first came to Europe in the 14th century and was celebrated for its superior quality. The factories around Europe worked hard to crack the code to make the same fine quality. And then 400 years later in Germany, they finally figured out how to do it and the Royal factories all over Europe started making designs that are basically knockoffs of the original porcelain from China.

It sounds like you do a lot of research about the history of these objects?

I do, but at the same time I try to avoid things that depend on research in order to be understood. I pick objects that everyone has a certain knowledge about. Every viewer will have a different entry point into the meeting with for example a hand-rolled cigar, but we all have one tool or another ready to pick apart the baggage they carry.

Are the objects two things at the same time: both the object and a reference to it?

That’s something I keep on returning to in my work. I am attracted to objects that are both themselves and representations of themselves in different ways. Like the porcelain I work with is an imitation of another porcelain. An actor crying is both pretending to cry and actually crying. The human hair wigs that repeatedly make new appearances in my work, are frozen in one hairstyle almost like a photograph, but they are still made of actual hair. Human hair for use in wig making has always been obtained from parts of the world where human time and labor is valued lowest. Most of the wigs produced today come from India and China and they have, much like any other representation, been reworked, dyed, bleached, and permed to be traded in the European market.

You look at the world through the physicality of the objects. How do you feel about the parallel world that is online, how to address that and capture a certain digital tension?

I haven’t yet encountered an aspect of the digital reality that I needed to work with. I don’t know if that’s because I actually fetishize materiality to some degree. I don’t take my starting point in the material as a lot of sculptors do, though. I’m interested in a lot of things, but not all of them have a material presence that speaks to me. When I can’t find that presence, it doesn’t become an artwork.

My process is always about being curious about things, searching until I find a particular object or behavior that articulates it, both physically and historically.

So, for example sitting here with my marble eggs in my hand, they speak to me about everything – from industrial food production to the origin of life.

On the Belgian shore you have a piece consisting of several statues. What’s your take on statues?

I was looking at the conflict between permanent statues and the fluctuating standing of the people they represent. There is a prominent statue of King Leopold II on the Belgian coast. There have been countless petitions to have that statue removed. It is a sad monument but the important thing to note is the meaning it carries now is completely different to what was intended when it was produced. For me going into that context felt like the dialogue partnership was already there, so the work was in a way a direct response to the presence of this statue.

What kind of response did you did you anticipate receiving?

Traditionally, public statues commemorate specific people: the majority are of men of some distinction, often on horseback, and they are known and referred to by their names; whereas women and children are usually anonymous and often nude. But once the statues leave their original location and enter the market again, the names are often lost and a certain flattening of hierarchies takes place. For this piece, I went through a lot of the antique dealers in Europe and collected all the bronze equestrian statues I could find. The final work is made up of four unidentified men on horses; a Roman warrior, an English knight, a polo player, and a jockey that I brought together in formation. The tide makes a daily ritual of swallowing them every day as they disappear and reappear.

Men, 2018, Found bronze statues, 500 x 200 x 250 cm, Permanent installation, Beaufort, Nieuwpoort, Belgium, Photo: Frederik Werkbrouck

Tragedy, 2012, Persian rug, dog performance, Dogma, Metro Pictures, New York

Installations with objects are not the only medium you use. Tragedy, first put on show at Art Basel in 2012, incorporated real dogs, with the twist of them playing dead – until snapping out of this state. How did this piece come together?

I tend to return to any type of behavior that is repeated. Behavioral logics are passed down just like the objects around us. Both can be read as products of collectively produced patterns, so even almost invisible things like a bathroom sink or chain smoking are inherited motifs that are alive and they’re used and interpreted and understood in different ways as they transform over time.

There are a number of actions used for training dogs; you teach them to sit, lie down, and oddly, it is not uncommon to teach them to play dead. The way the piece is playing out is that a trainer brings a professional actor dog into the exhibition and asks it to play dead on a rug. The dog stays immobile for five minutes. The action somehow feels like a spell that freezes everything in the room. It is an uncanny moment where the dog appears mummified or taxidermied and then it gets up again and the illusion is broken.

What do you make out of this interplay between dead and alive?

As a viewer you too feel paralyzed in the room, up until the point when the trainer signals to the dog to jump up. It is a physical experience of what representation is: like a flower that is pressed and becomes an image of itself. Tragedy is a key work for me. When I saw it for the first time, it was clear to me that this was what I had been searching for: this glutinous, elastic, double identity, that coexists in a single experience. It creates a tension so intense, it quivers.

How did this experience change you?

I was working in a similar way before, but it was as if this piece revealed to me what I was doing or what sensation I was searching for. When the birdcages didn’t come together at first it was because that feeling wasn’t there. I keep returning to the dogs; they became the yardstick for everything else in my work.

If we gather all the objects you have together, what narrative unfolds?

I try to dig for answers in the spaces that are unintended and collective. I am looking for the hidden power structures that make up our global society. Clues can be found in anything, from the place, the objects, and behavior around us have originated, how they have been produced, how they have traveled, how they are traded, how they attain meaning and value, and how this has changed over time. I want to look at that and I would like other people to look at it too; in order to see those patterns that we overlook and to take in the full complexity of our reality. I guess I’m collecting these objects because they are the best and most truthful witnesses and testaments to our world order.

Empire, 2019, Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 94 × 44 × 33 cm, European Interiors, Croy Nielsen, Vienna

Empire, 2019, Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 94 × 44 × 33 cm, European Interiors, Croy Nielsen, Vienna

Interview: Rasmus Kyllönen

Photos: Simon Dybbroe Møller