Peter Jellitsch’s conceptual drawings in black and white oscillate between the digital and analog world. The esthetics and lightness of his Data Drawings cover the fact that they are packed with numeric information, and, to the interested viewer, they unfold a narrative about the visualization and transformation of space and processes connected to our daily routine. We met Peter in his studio in Vienna’s Josefstadt district to talk with him among others about his first career as a cabinetmaker, the attraction of Pokemon Go, and about the US, to which Peter owes an early development of his artistic career.

Peter, we are in your apartment in Vienna’s Josefstadt, where you also have your studio which appears to be very tidy. Apart from the monochrome pictures on the walls it looks rather more like a “workplace”, than what people usually think of as a studio.

I actually come from a working background so to speak. I trained as a cabinetmaker and I didn’t complete high school, although I later caught up with the high school diploma, or more precisely, the Berufsreifeprüfung (BRP), an educational high school diploma equivalency program which in this particular form, is provided only in Austria. This program gave me the opportunity to study art. From my time in cabinetmaking I have preserved a very structured approach to work. I have always liked to do my work in regular work hours. Now, that I no longer have a boss, I make my own rules and follow them. I believe that even if one looks at my work superficially one can see this structured approach.

That’s right, your pictures appear very structured. They’re quite painstakingly built up.

Yes, they really are. I spend incredible amounts of time in front of large pieces of paper like the ones hanging on the wall. I love to sit here by myself listening to an audio book and just drawing. This detail-oriented way of working is very meditative. Despite my very structured way of working it can happen that I am so immersed in my work that I suddenly notice that it is almost noon and I haven’t yet brushed my teeth. (laughs)

As a cabinetmaker did you also work in a similarly meticulous and concentrated way?

Perhaps, however I think that in my work two essential aspects come together: on the one hand is the idea of manual work, this I undertook in my role as a cabinetmaker. The additional factor, however, is that drawing is also very important to me. No matter what I do, I always return to paper.

How did you get into cabinetmaking? Did you always have the desire to work with your hands?

I come from a working class family. I grew up in communal construction and I am the first academic in my family. It was always assumed by my parents that I would most likely become a worker or employee; training for a manual trade was an obvious direction to them. The decision was actually quite pragmatic. I became a cabinetmaker only because there was a woodworking company near by and a friend of mine had already completed an apprenticeship there. At the time, I didn’t even appreciate wood as a natural material, although that has changed in the meantime. So I could just as easily have become a car mechanic.

Regarding your down-to-earth parental home, how did your parents feel about your striving for something higher, your pursuit of an artistic career?

It’s funny, but my parents never had a problem with the profession of artist. The reason may be that my father, a professional tiler, had been commissioned for art-in-architecture projects. The artists with whom he worked were actually craftsmen who worked sculpturally and artistically. For him art has always been a craft, whereas the profession of the architect has actually been rather alien to him. We live in the country where we do everything ourselves. What would we need an architect for?

So your parents didn’t have the classic apprehension at the prospect of their son embarking on the precarious life of an artist?

No, fortunately I had received appreciation of my artistic achievements relatively early. When I graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna in 2010, I received the Outstanding Artist Award for my diploma thesis, a prize awarded by the Federal Chancellery every year that provided a small financial cushion after the degree allowing me to experiment in all directions for one year without financial pressure.

Looking at your “Data Drawings” as you call them they actually look as if they were digitally rendered topographical maps of mountain ranges.

Yes, at first glance they may indeed appear like that. In reality, however, they are visualized measurements of digital signals and data that are invisible to us, but that we are exposed to every single day. My work is focused on the transformation and visualization of processes that relate to our daily life. We are actually constantly existing within invisible networks, remaining from the moment we get up in the morning until we go to bed at night, connected to the internet via our smartphones, tablets and laptops.

We use streaming data and at the same time generate vast amounts of data containing accessible personal information…

Yes, it is eerie when you think about it. And we accept it quite unthinkingly! However, once in a while we ask ourselves the question: Who is behind it all? Who is profiting from all the data? What conclusions can be drawn about us and about our lives?

How is such a “Data Drawing” generated?

First I take very precise measurements of WLAN data streams in a specific space with a special app on my iPhone. These are made visible on paper in the form of a kind of 3D diagram. Since I am drawing by hand, the drawing can never be entirely exact. But for me that’s also the charm – this tension between precise measurements and human imperfection. The idea, however, is that every individual line, every surface in my pictures is based on numeric information and therefore the pictures so to speak write themselves.

Do the measured data define precisely how a picture is going to look? Or do you sometimes intervene cosmetically?

In my initial records I try to be as precise as possible. The idea of an exact depiction ends on the piece of paper. By applying the information again and again a repetitive mountain-and-valley structure is formed. It is possible that I superimpose data taken on different days or weeks. In that moment also esthetical decisions begin.

So esthetics plays a certain role in your work?

Yes, a very big role. The term black-and-white is very prominent in my work. On the one hand, I couldn’t see a real sense in working with color. I was more influenced by the fact that I dealt with phenomena based on zeros and ones. My work is just that. The zeros are the paper. And all the materials I use such as acrylic, graphite and colored pencil are black. They are the ones that complement the zeros. Seen this way, I don’t work in black-and-white but in black only.

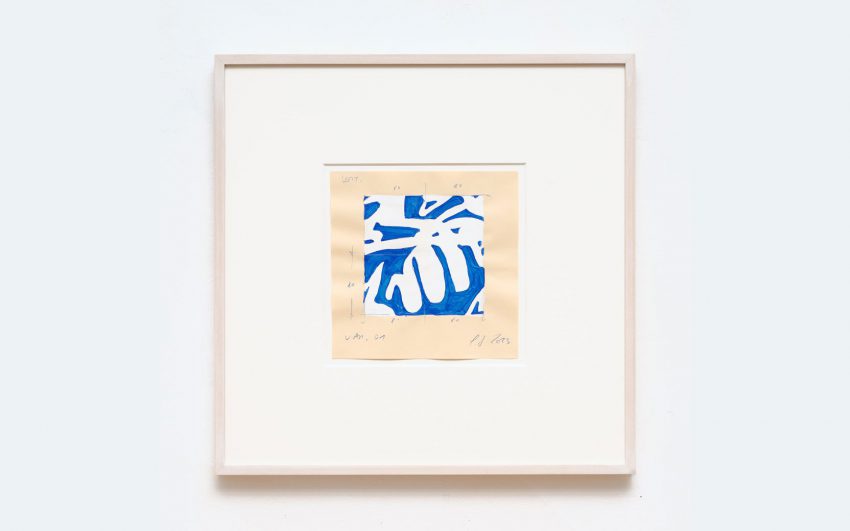

Bleecker Street Documents, 2011/12

Measuring Notations (Wi-Fi network): pen, pencil on paper, 12 sheets, each 20,3 x 12,8 cm / Object: coated ureol, 80 x 24 x 120 cm / Image: inkjet print, 100 x 140 cm

Do you want to trigger something specific in the viewer with your pictures or do you want to make a statement?

In particular, I would like people to enjoy my work without the burden of background information, because every piece of paper already contains information. Primarily, I want them to profit esthetically. And it was important to me right from the beginning that there is something that I as the author can speak about. There is nothing worse than people not knowing what they are doing and needing an art historian to speak for them. One notices very quickly that the information is imposed and has nothing to do with the work.

In recent times, the entire world has been in a “Pokemon Go” fever. The idea of tracking down with the use of a smart phone, invisible creatures in one’s surroundings, has evidently exerted a strong fascination on people. To make the invisible visible... Your work follows a similar concept, doesn’t it?

Exactly! It was very exciting to watch. As a child of the 1980s I was especially influenced by science fiction films such as “Tron” and by videogames. I was already fascinated by the idea of being drawn into something and immersion in other realities. Being-sucked-into something and immersing-into-other- realities fascinated me already at the time. We are actually moving more and more into this direction. The boundaries have become increasingly blurred, and “Pokemon Go” visualizes this tendency particularly well. It is the very idea of being able to communicate with another world that has a strong influence on people. This may be taking the matter too far now, but from an art historical point of view the phenomenon could be explained in different ways, for example in terms of the occult, that is with the idea of being able to connect with the beyond.

How did you perceive of the idea of collecting data that are invisible to us and to translate them visually?

Spatial concepts and their illustration have always interested me. Architecture had been a part of my studies at the academy. I’d been particularly fascinated by programs that can model and simulate spaces in 3D, and this topic has gripped me ever since.

It began with my diploma thesis in which I dealt with a review of Vienna’s urban space and with redrawing the city. During my research on the city I found out that around 1881 the first telephone connection was presented to the public at the Schillerplatz, which amongst others houses the Academy of Fine Arts. In this context I also found out that the greatest density of mobile phone masts in Austria was measured at Stephansplatz, because most people stay there at the same time in one place telephoning and using data.

I wondered how the first district would look in a dystopia, in a sort of negative utopia, if only optimal network coverage were to be determined. As a consequence, here I might have to pay more per square meter for better coverage as in other places or the other way around, perhaps I would have to pay more in order to be in a place where I would not be surrounded by data. So I walked through the first district in order to find out where and how fast I could download Marshall McLuhan’s Global Village.

This resulted in three models: One showing a frequency card from 2000 – at the time there were fewer masts but with higher frequencies on the roofs, resulting in higher swings in the model. Another model from 2010 where change can be clearly seen because of the move to the use of many small transmitting units with lower frequencies; this model is more balanced. The third model shows the anticipated build up of density in the first district.

Were these measurements that you took in Vienna at the time already truly scientific data?

Funnily enough some architects contacted me at the time wanting to engage me to record radiation measurements for an urban extension project. But I declined because I had not intended to describe or verify the phenomenon with scientific precision. It was only an attempt to describe the world or a part of the world in a different form.

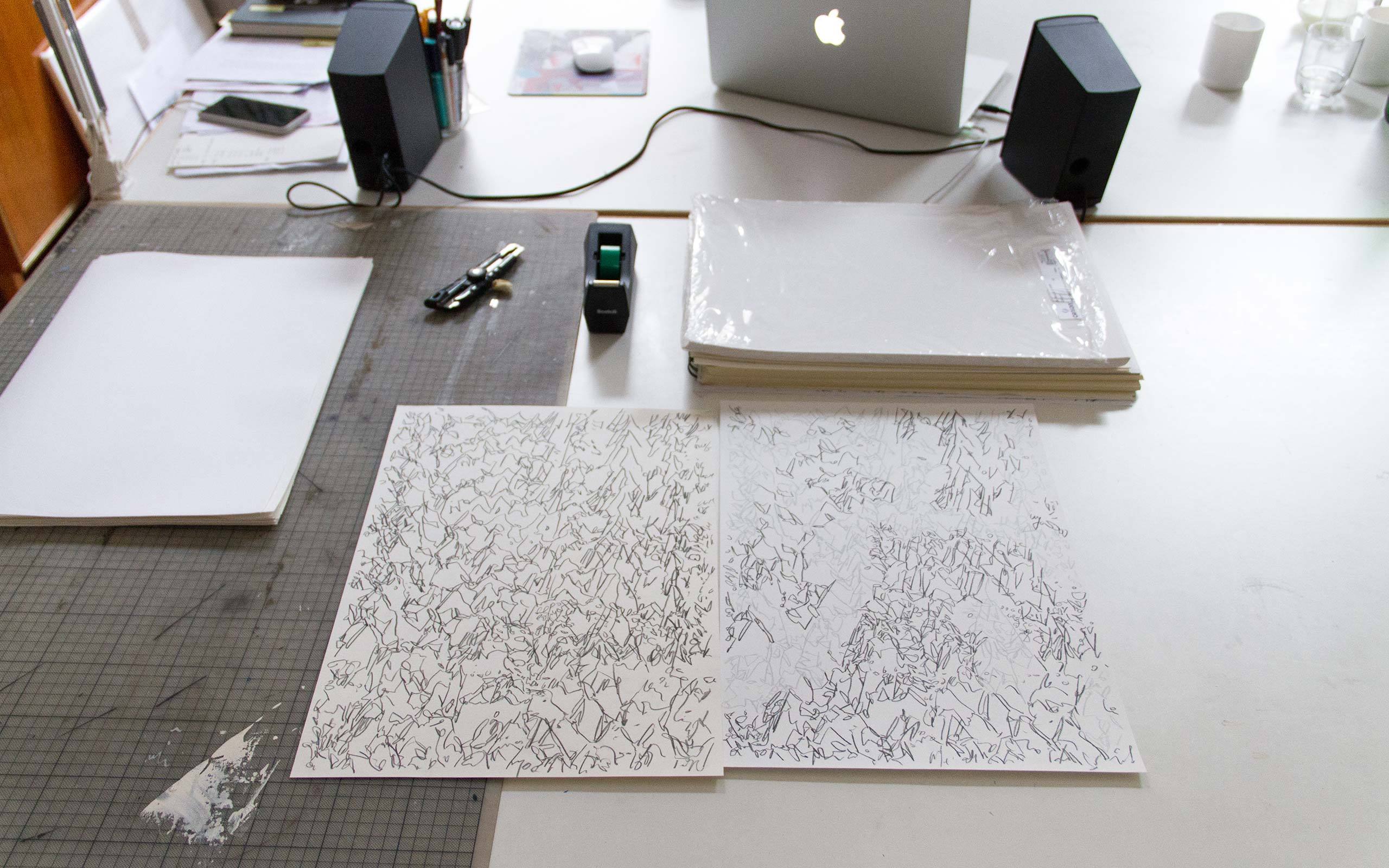

Data Drawing 52+53, 2016

Pencil, acrylic, crayon, lacquer on paper, each 170 x 120 cm

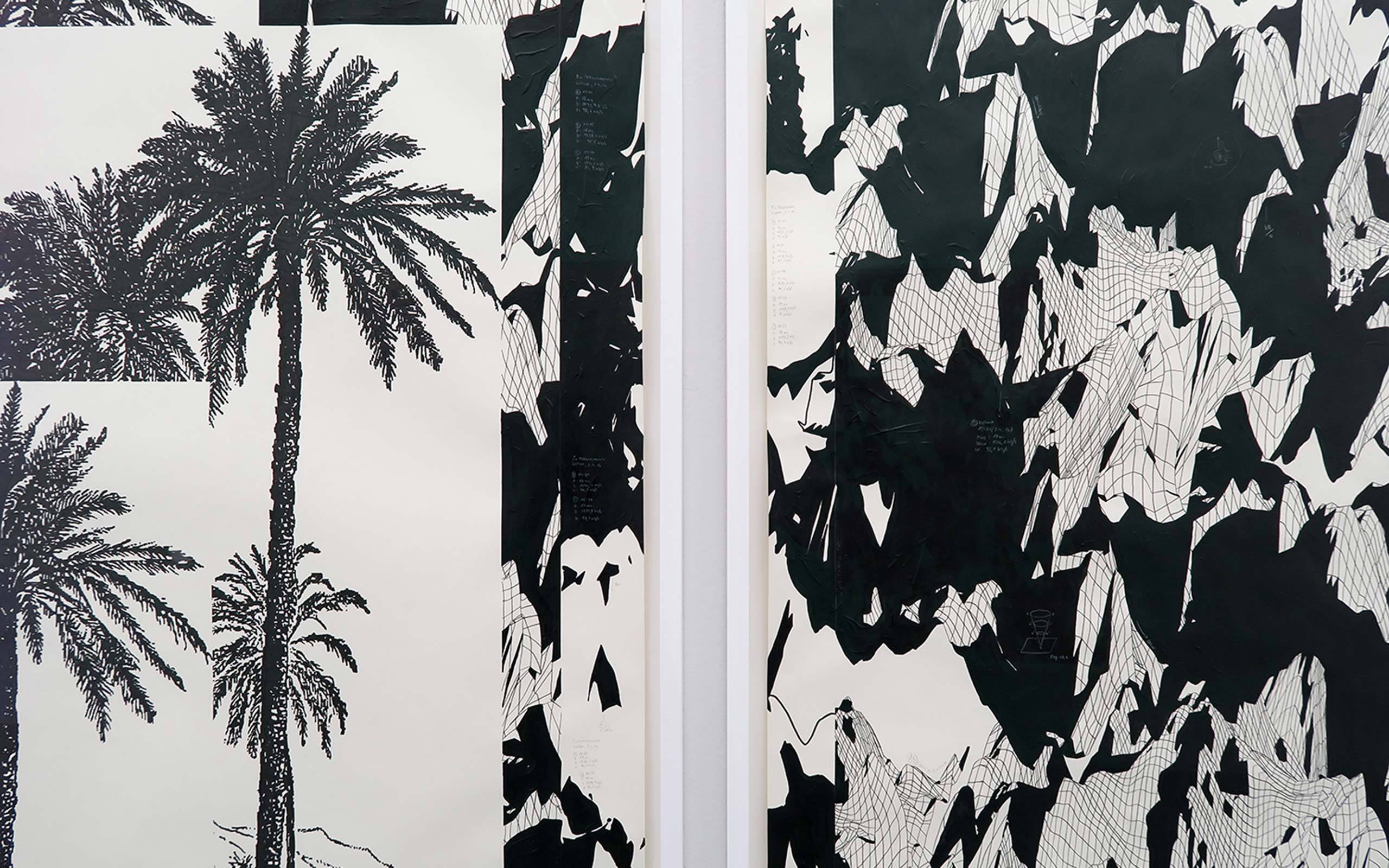

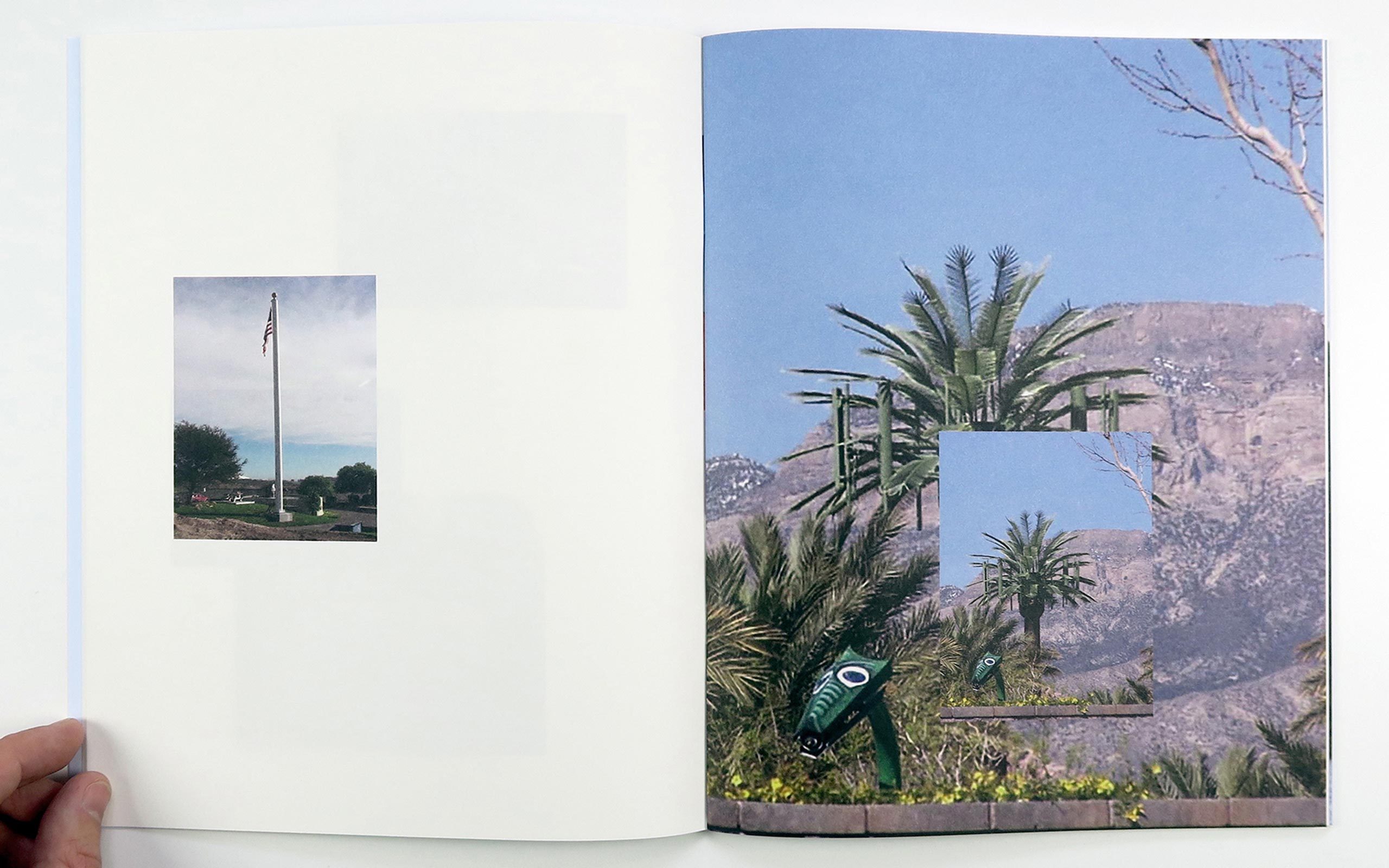

Palm Tree Antenna, 2016

48 pages, numbered edition of 300, self-published

Through the Outstanding Artist Award with which your diploma thesis was honored you were granted the opportunity to pursue a project abroad right after you graduated from the academy. How did you make use of this opportunity?

This gave me the chance to work for two and a half months in New York where I developed the idea of spatial measurements further – in the apartment of a collector, in which I lived during my stay in New York. I had borrowed a measuring instrument from the Technical University Vienna and experimented with various Apps for the iPhone that measure environmental information. A numerical diary, or more precisely 12 sheets, filled with figures evolved in the two and a half months – these represented values recorded on a daily basis while staying in the room. Back in Vienna I processed the data collected in these records over several months with the aim of learning how to speak about a space without describing or showing it in a conventional manner. The result was Bleecker Street Documents, a project which later on developed in the beginning of my Data Drawings.

The US quickly became a springboard for your artistic career.

Yes, that’s true. The US was an environment that promoted me right from the start. As I’ve already mentioned, my stay in New York was initially facilitated by the Austrian Federal Chancellery. At the time, there existed a super interesting blog which went under the name of butdoesitfloat.com. My works were shown there once giving me an incredible visibility.

Then a curator from SFMOMA contacted me quite unexpectedly by email wanting to know more about the background of my work. He was presently planning the exhibition Field Conditions which focused on the question of space and how it could be visualized, and he thought that I would fit in well. We began communicating via Skype and a few months later my work was shown in the group exhibition Field Conditions beside works by Sol LeWitt and Tauba Auerbach. It was my first exhibition outside the university context. What still impresses me and for what I am very grateful is the fact that SFMOMA was so experimental at the time and actually took a great risk. In the meantime, my works are also in the collection of SFMOMA among others.

Although the US was such a supportive environment for you, you returned to Vienna two years ago, why did you come back?

Yes, I am asked that quite often. (laughs) It’s simply the work environment and the opportunities as well as the very moderate living expenses here. That is something very special. I love the US despite the depressing political developments, which unfortunately exist all over the world and not only in the US. I could not have afforded to study in the US where the art sector is very elitist at the moment. In the American art scene there is no public funding, there are no public institutions that support art. That’s completely different in Austria, especially in Vienna. And it is quite remarkable that the Austrian educational system makes it possible for every student regardless of his or her social background to be able to study given enough willpower and effort.

The US apparently continues to exert a certain fascination on you. You spent time there in 2014, this time in Los Angeles. Since then one frequently discovers depictions of palm trees in your pictures. Is this a tribute to your temporary residency?

Exactly. In 2014, I was invited to participate in an artist-in-residency program at MAK in Los Angeles as a scholarship holder of MAK [Center for Art and Architecture] Schindler Scholarship. I noticed the mobile phone and transmitter masts, which were camouflaged as palms to blend into the cityscape. These Palm Tree Antennas are almost invisible, but omnipresent. I took much interest in them, because they represented a continuation of the topic I had been concentrating on so much during the past few years. In the meantime, an artist book has emerged from this intensive preoccupation with these Palm Tree Antennas; the book is distributed by Printed Matter in New York.

A location without mobile phone network would be impossible to find here in Austria, wouldn’t it?

Oh yes, it does exist: in Klausen-Leopoldsdorf! (laughs) That’s precisely the question that I’ve asked myself while I was working on my diploma thesis. Forty kilometers outside of Vienna I found it with the help of a coverage map of A1 I –a small forest section near a village of 1,400 inhabitants where you could in fact stand in a “zero data zone”, because one is exactly between the range of two radio masts.

Have you become more careful about how you’re using your personal data in the net?

Yes, I think so. It is a fact that at the moment when you are using a new App or a Social Media network you have to involve yourself in a deal concerning your data. It is almost impossible to avoid that, for without sharing data you don’t get through the door. Therefore I am probably more conscious about my use of data, nevertheless I cannot free myself from it.

What projects are you on to next?

A book of mine which focuses on the Data Drawings will be published by Verlag für moderne Kunst. The book spans an arc from the recent drawings to the early visualizations of my measurements from the time in New York. It contains texts by Marlies Wirth, Joseph Becker, and Sébastien Pluot and is entitled The way you moved through me after a quote by the artist Laurie Anderson. The title has been kept deliberately vague to leave space for interpretation. It could for example be interpreted erotically or to refer to the invisible frequencies with which we are pervaded at every moment. The readers of my book can come to their own conclusion.

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer