The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Be it carving, weaving or tufting, Pia Ferm defines herself as a sculptor. In her neat tapestries, hand-trimmed to keep the surface alive, the Swedish artist mixes a pretty medium with humor, creating figures that are frozen in time like cartoons. Time is essential for Ferm but not in the way you might think. She has plenty of it.

Pia, you have recently moved into a new studio in Frankfurt. How does one day’s activity at the studio look?

I start my day quite late and don’t come to the studio until after lunch. I stay there until late at night instead as my most productive hours are between five and one. There’s something about knowing that the rest of the world is finishing up for the day while you are alone working. It creates a separate universe for me.

Your first exhibition at Galerie Judith Andreae in Bonn is called Bread and Butter. How did you choose this title?

Stepping into the exhibition is stepping into my head. It’s a good overview of my universe. The title refers to both everyday life and its bare necessities and my everyday practice in the studio and the wish I have of this becoming my livelihood. It’s summarizing a period of work but represents also a new ground level, from which I now can take off. I’m finally out of school, have my own place, and finding my own working rhythm. I’m closing one chapter and opening another at the same time.

Tufting, the technique you use for creating the tapestries, seems to be labour intensive and complicated. How would you describe this way of working?

The tool was developed in China in the early 1960s, with the intention of accelerating the craft process in the carpet industry. If you want to fill up a surface monochrome, you can work fast. But I use a technique comparable to molding with colored clay. You can choose the length of the yarn, in order to build up a relief. By combining four to six threads in every stitch, you can create an endless variation of color shades. I work from the reverse, pushing the yarn through a stretched fabric, which means I always build the image up mirrored to the finished piece. I’m constantly moving from one side to the other to keep track of what’s happening on the front side. Simultaneously, I’m adjusting the surface by trimming it with a pair of scissors.

I’m still learning how to master the technique, but for every project, my relationship to this fantastic machine becomes more intimate. I want to let my hands do a lot of the thinking. I was completely enraptured by the technique when making my first rug. I couldn’t see myself in it. Thanks to finally having my own studio, I can afford to fail and fix things. Earlier I had to play it very safe with the tapestry making; because correcting a failure would have meant an interruption in my schedule which would have left me no time to complete the work since at the time I was subject to the restriction of renting a tufting studio in Sweden.

How did you become the artist you are today?

I couldn’t get into the school I wanted to in Sweden and found myself studying in Frankfurt am Main instead. About halfway through my studies I figured out how things worked – what my school could give me and what I had to look for elsewhere. My first encounter with stone as a material was through a month-long workshop at the Salzburg summer academy. The reason I started working with textiles was that I found a tufting class in Sweden. I applied for it while still covered in stone dust from the old quarry at Untersberg. I was torn whether to incorporate textile materials in my practice because it is something that has been more of my hobby of mine, doing stereotypically female things like taking care of my home and clothes.

How would you describe the purpose of school for your profession?

I met people and I got opportunities here that I wouldn’t have found anywhere else. I’m not good at networking or mingling. But still, the art scene in Frankfurt is small. If you are bad at networking like me, but have work to show, you will find a way to create a space for yourself that can serve as a stepping stone for you. I guess you could do it the other way around, be good at interaction and then do the work. But that’s not how I work.

Despite your ambivalence with making textiles part of your artistry, you gave in to the material in the end. How do you view this process looking back?

I have always been fond of the textile craft, but I felt it belonged to the domestic sphere. I didn’t want to turn into a “female textile artist” and then having my work interpreted through domestic glasses and reduced to a political statement. The prettiness of the material gave me doubts too. How was I supposed to deal with it without just making something trashy – because that’s also not my style – yet at the same time acknowledge a certain degree of humor? My works are quite neat, having clear outlines and a certain finish to them. My main concern was not to fall into an aesthetic that was really trendy – using something crafty and then making it trashy. I would say I have managed okay. I allow myself to be in a place where I can defend making things that are beautiful, because it doesn’t mean that they therefore would be without content. I’m thinking a lot of how an artist can dare to be romantic and make things that are beautiful without it having to be a gesture of beauty, without chickening out and drown it in some cool irony. It’s a sincere approach but you have to fight for that position. It’s easily made fun of.

Is it a rug, tapestry, a textile painting? – How would you describe your textile pieces?

You can call them tapestries or weavings – even rugs if you plan on putting them on the floor (but then it’s an art piece on the floor!). I tend to think of them as wall objects – textile images or sculptures that are hung on the wall. In comparison to my small weavings, they’re quite cocky. They demand a lot of space when you hang them on the wall because they absorb all of the light and sound around them; I like to refer to them as my macho paintings.

Pia Ferm, Das große Selbstporträt, 2020, hand tufted wool and linen tapestry, 185 x 240 cm

Copyright: Pia Ferm, Courtesy: Galerie Judith Andreae, Bonn, Photo: Jiyoon Chung

What does starting a new tapestry look like?

I don’t do much sketching, but I have a bunch of sketchbooks for visual notes of shapes and patterns. Sometimes one small drawing can work as the whole piece, other times I start from one and make a new drawing or combine two different shapes. I can be too hasty when settling on a sketch, so I like to leave them in a drawer for a while before making a final decision, because otherwise, I will tell myself that I’ve made a really good picture, then realize halfway into the process, that it’s not as interesting as I thought. I find that the rule is, the more carefully I choose the image, the more pleasure I have working with it. I used to have my sketches colored but that felt like I was following a recipe. I got stuck looking at the picture and wanting to follow the logic that I had already pinned out for myself. Using a black and white picture gives me more freedom to develop the image as I go along.

Does this mean you have slowed down your work?

That’s connected to me starting my studio, allowing myself to give my work the time it needs. I insist on an unhurried approach necessary for the expansion of my universe of images. There is no law saying that we have to speed up our work and produce an excess of quality images constantly. It’s impossible when everything is done already. I believe in repeat and refine.

On average, how much time do you spend with one piece?

The bigger rugs take between three to six weeks, a small one can be four weeks. But it’s the motif that sets the time rather than the size. I might have a lot of small lines with different shadings inside of them or a lot of white space, then it becomes particularly laborious. The easy way out would be to make a uniform white surface but that would feel completely dead. This is why the white surfaces consist of different white yarns of different thicknesses. I might add some pink, gray, and blue-ish tones as well. The end result depends on what yarn I happen to have. If I’m feeling rich I order custom dyed batches from a small manufacturer in Sweden.

Is there a part of the process that you enjoy the most?

I love the laborious parts when all of the most crucial decisions are already made: hovering over the weaving frame, sanding my stone piece or cutting down a finished rug from the frame and trimming it by hand, I have a pair of fancy precision scissors for that.

Do you know what kind of spaces the pieces end up in?

They are mostly in people’s homes. I think is a nice quality my textile works have: they take up a lot of space, but are suitable for a normal home. It’s the best of two worlds in a way: if they get a lot of space, they can be quite dramatic, lending an almost sacral feeling to the space. In a smaller room they work the way a painting would.

How is carving stones different from tapestry making?

Setting up my studio for the past year hasn’t given me many days at my stone working place. Working with stone is really the opposite of weaving or tufting. Instead of building something, I’m subtracting material. It’s so absolute in the way that you can’t undo what you did. Being quite conservative in my ways of working, often getting stuck in the same tracks, stone carving forces me to think differently.

With that said, working on diametrically opposite approaches to crafting, you describe yourself as a Bildhauerin, an image carver. What meaning do you put into that?

I think about myself as someone who makes images, working in the sculptural field. My works are images, whether it’s a three-dimensional sculpture, a flat, woven work or a tufted tapestry. They are all drawn doodles. I’m working with icons, pictograms and symbols. In front of me I see figures floating in the room taking different shapes and then reappearing in a wall-hung image.

You want to promote a more nuanced definition of what an image is. Can you explain your thoughts?

This is something that I have been thinking about for quite some time: what do we mean when we talk about an image? My work is often understood as something that is referring to painting. But as I see it, this is not the universe I operate in. So much art is forced to somehow “aspire to be a painting”. I think you can make works intended for the wall, even if they have four corners, without them being read as paintings.

These figures that are ‘alive’ to you, how do you catch them in a single frame?

You invent a logic for yourself: how to place the objects in the picture, asking them where they are coming from and where they are going. It’s all very similar to drawing a cartoon; you are telling a story but with stylized stop frames. You present caricatures of figures that at the same time talk about what they represent. They hold a lot of meta-information. By repetition, in a different context, they become a sign both for themselves as well as for something they represent.

Can you explain further what you mean?

Think about any drawn figure that gains a wider audience. First, it is just a funny comic figure, maybe a caricature addressing an argument in a political debate. The more often it occurs, the more you learn about its universe and of its different meanings within it. It gains a life of its own.

What’s next for you?

First, I want to weave something big, which is something that I have wanted ever since I finally dared to start weaving. This would be a therapeutic tapestry project without an absolute deadline; a weaving I can turn to whenever I feel stuck elsewhere. As a slow and meditative practice it offers a way out. Second, I just want to keep making more of everything. The more my universe expands, the more sense it seems to be making to me.

Pia Ferm, Still life no. 4, 2021, hand tufted wool and linen tapestry, 175 cm x 85 cm

Copyright and Courtesy: Pia Ferm and Galerie Judith Andreae, Bonn 2021, Photo: Ben Herrmanni

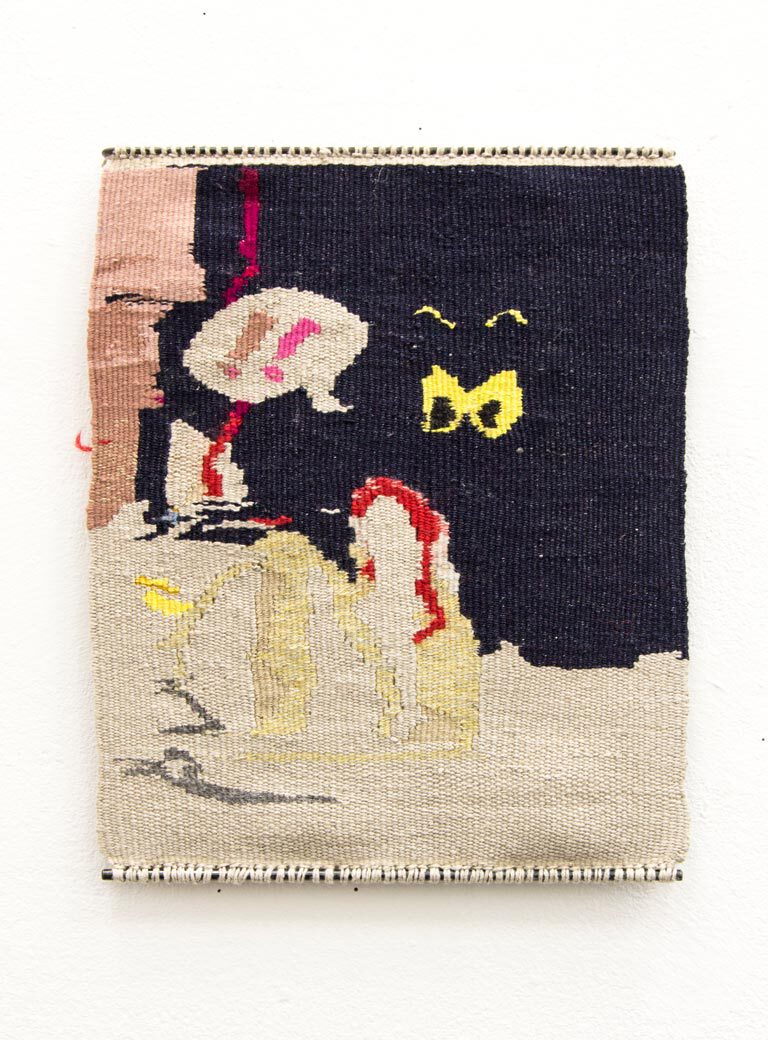

Pia Ferm, Jonny, 2019, Linen, cotton, and wool yarns on linen chain, metal mount, 40 cm x 30 cm, Copyright: Pia Ferm; Courtesy: Private Collection, Brussels

Pia Ferm, Bonnie and Lux, 2019/21, Untersberger Marmor, Diptychon, ca. 70 x 45 x 20 cm and ca. 80 x 58 x 18 cm, Copyright and Courtesy: Pia Ferm and Galerie Judith Andreae, Bonn 2021, Photo: Ben Hermanni

Interview: Rasmus Kyllönen

Photos: Sabrina Weniger