Obsessed with colors, patterns, and materials from raw ceramics to stretchy textiles, Polly Apfelbaum creates site specific installations, that surround and challenge the senses of the viewer. Born in a farmhouse in Pennsylvania filled with folk art, she moved to New York City in 1978 where she started exhibiting her art. Ever since her vibrantly colorful work has explored the lines between performance, painting, and sculpture. With her “fallen paintings” she turned the otherwise disregarded gallery floor into a valuable exhibition space.

Polly, we are in your studio in an old barn in upstate New York. I see a long table with a series of painted ceramics; I see piles of colorful fabrics, and some exhibition architectural models. What are those?

They are models of the spaces of my upcoming shows at Spruance Gallery, Arcadia University in Pennsylvania, at Magasin III Jaffa in Tel Aviv, and at Kunstmuseum Lucerne in Switzerland. So I’m working simultaneously on these different shows. The show at Arcadia is mostly ceramics. My idea for Lucerne is to make a huge crazy quilt out of all of these fabrics you see piled up in the studio. A “crazy quilt” is a quilt made up of scraps, or patchwork, with no repeating pattern. They are going to be two crazy quilts actually: One with solid colors and one with prints. Some of the patterns are just hilarious. There is one with smiley faces that drives me crazy. I buy up remnants from the fashion industry. It’s used for theatrical material, but also for bathing suits, gym wear, and skateboarders clothing. These synthetic fabrics lay very beautifully on the floor.

What will be the base for the quilt that you’ll be showing at Kunstmuseum Lucerne?

It will be squares arrayed on the floor in a loose grid pattern. Here in the model you can see the layout of the rooms. It’s a beautiful building by Jean Nouvel overlooking the lake. It’s going to be two rooms of fabrics and two rooms of ceramics, small ceramics on the floor. It will be a two-person show, including drawings by Josef Herzog, a Swiss artist, who is no longer living. All of these shows were originally scheduled for before the Corona pandemic, and they were all postponed. Now, all of a sudden, they are back on, rescheduled for an intensive six-week period this spring. The show in Tel Aviv is based on an older floor work Red Desert that Magasin IIII owns. So the show is Red Desert/Red Sea/Red Mountain, and it includes some newly fabricated rugs and ceramics. At the same time, I am working on a show at Arcadia that is based on the work of a Pennsylvania Dutch outsider artist named David Ellinger.

We are meeting here in your Elizaville studio, but you have a second one in Glenside, Pennsylvania, very close to where you grew up. What kind of work do you do in each place?

Well. It’s complicated – like so much around the pandemic. I have had a studio in New York City for more than 40 years, but I haven’t really been working there. These past 18 months, I have been splitting my time between this studio, where I mostly do drawings (although there is a kiln here) and Arcadia. I wouldn’t consider Arcadia my studio. It’s an artist’s residency and it’s very particular to a project that I’m working on. A couple of years ago, I received a phone call from Richard Torchia, the director of the gallery there, asking me if I would do a residency at Arcadia University. He and Gregg Moore, the head of the ceramics department had seen a show I had done in New York called The Potential of Women, which included about 130 ceramics and which got them very excited. I received some grants to support this work, and the idea is that what we produce in the residency will turn into the show. Because of COVID, the show was put off a year and it just grew. They have been very generous. It’s really more like collaboration with Gregg and his assistant Rachel Geisinger. As you can see in the corner of this studio, I have a small kiln and I was doing ceramics here; this residency really has brought the ceramics full front. Gregg has brought a very high level of expertise to the project – we have developed 100 new colors of glaze for this project, and of course there I have larger kilns and more facilities to work with.

A lot of the mediums you work in – pottery, weaving, etc. were for a long time considered women’s crafts rather than art; just think of the situation at the Bauhaus. I was thinking of Gunta Stölzl when I saw some of your recent weavings. Is that someone you relate to?

Yes. I’ve thought a lot about that. It’s something that applies to craft in general – Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, and so many others women who have been marginalized. But also this idea that you just do one thing – painting, say, or sculpture. Look at Sophie Taeuber-Arp, who is getting a lot of attention this year. I think for a long time, people didn’t know how to categorize her because she did so many different things – drawings, paintings, architecture and design, fashion, objects, needlepoint, puppets, jewelry – so many critics need an easy label, and I think many women didn’t have the luxury of just doing one thing. There’s a big show now at the Tate Modern, and I am looking forward to seeing it when it comes to New York. I would also say that growing up in Pennsylvania, around Pennsylvania German art and the Barnes Foundation, which showed Matisse and Picasso alongside quilts, pottery, tools, and Navaho rugs. I never thought there was a difference. When I was studying painting and sculpture, I saw how all these things were left out. But they meant so much to me and I wanted to figure out how I could bring them back into the picture.

How did you begin creating art? Was there a particular trigger moment?

I’ll give my parents credit for being interested. I grew up in an old farmhouse surrounded by folk art and quilts and Pennsylvania German folk art. They collected china and spatter ware, and also old furniture and paintings by David Ellinger, and they took me to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. So I was exposed to art when I was very young, without any sense of hierarchy or value judgment, beyond beauty and utility. I was exposed to interesting work, but it was also stuff that people didn’t think was art, like rugs or Amish quilts, which make me think of Agnes Martin. I guess that’s also where my love for abstraction comes from. My parents fed my curiosity and imagination.

Were your parents folk art enthusiasts?

There was a moment in the 1960s, when people were starting to get interested in collecting folk art. It wasn’t expensive either. I remember as a kid, my parents took us to Amish auctions. There was a barn and they had the quilts outside and animals running around. It was colorful. It was not art in a white cube.

Where did you get your sense for colors and patterns?

Throw in the 1960s Marimekko clothes my mom was wearing. She’s 95 now and the big decision of the day is still what she is going to wear. She is the most stylish ninety-five year old. (Laughs)

You studied at Tyler Art School, which at the time, was close to your childhood home. Then you moved to New York City in 1978. Did New York change the way you think about art?

New York in 1978 was a totally different city. The art world was small at the time – maybe a dozen galleries in Soho. Art school doesn’t prepare you for that. I learned by going to shows, meeting other young artists, and the discipline to make work. New York is where I became an artist. But you also have to understand there were not a lot of openings for young artists at the time. It was only later, in the 1980s, that I started showing, first at alternative spaces like Artists Space and White Columns, and then in the East Village, not Soho.

When did you consider yourself an artist for the first time?

At that time, you first had to figure out how to exist in New York, working part-time jobs and making time to make your own work. Fortunately, it was cheaper then. And we were already latecomers – we couldn’t afford Soho or Tribeca. My partner Stan (Allen) and I moved into a raw loft in the South Street Seaport area for $300 a month. Really raw. No glass in the windows, no kitchen, no bathroom – we would use the bathroom at the bar across the street in the morning. Because it was still a fish market then the workers, who were just finishing their workday would be downing beer and whiskey shots at 8 in the morning.

You considered yourself fortunate to be there at that time?

Absolutely. It was a time when things were opening up for younger artists, and interesting women of the generation before me. When I first got to New York, Paula Cooper was showing a lot of women – Elizabeth Murray, Lynda Benglis, Jennifer Bartlett… And I was looking at a lot of art. Richard Tuttle, Alan Shields, Alan Saret. There was a lot of stuff that I was interested in and I wanted to figure out how I could get that into my work. It was a very rich time to be a young artist. But you wouldn’t ride the subways after 9 PM back then! It was tough, but it was a good time too. I wouldn’t change it for anything.

Were you already exhibiting the fallen paintings that you are known for?

No. The first works that I had begun to exhibit were fabricated wood objects, but also based on folk art. So with what I am doing now for Arcadia it has come full circle. The falling paintings really started in 1992. It was a show at Amy Lipton Gallery in Soho called: The Blot on my Bonnet. The floor was an emotionally charged and irreverent space, a place where you throw things. It was actually Kurt Varnadoe who first used the term ‘fallen paintings’ to describe my work, later in the 1990s, but it is such a suggestive phrase that I have picked it up – both the physicality of something collapsed, fallen onto the floor, but it also has the connotation of a “fallen” woman, or a “fallen” angel.

What do you like about your art being looked down from above?

I think that people engage with it differently. It’s about a different point of view. I loved about the rugs that you could walk them – it literally brings the art down to earth. They make a place, and it’s also tactile – you engage it with your body. But maybe working with the floor was also opportunistic. All my painter friends were happy to have me in their shows. I wasn’t taking away their walls!

How would you describe the art that you do in a few simple words?

It’s a hybrid – I don’t like categories, and I think many things can be art. It’s trying to be very open to materials and ideas. It’s experiential in that I am still experimenting and learning. I learn from the material itself, paying attention to what it wants to do. I really don’t like things or ideas to be fixed beforehand. I have to do it myself to figure it out. Which doesn’t mean I always do it myself – I enjoy working with fabricators, who also bring something else to the work, something always unexpected.

But you do a lot yourself. You draw, you paint, you dye, you make ceramics, you weave…

I learned how to weave two years ago at the Haystack School of Crafts. A friend of mine, the curator Kate McNamara, invited me to do a show there and have a ten-day workshop. It’s a remarkable place, that’s deeply embedded in craft history and craft ideas, yet at the same time very open. They have ceramics, woodworking, it’s a kind of Bauhaus-like place. It was May, and still freezing cold in Maine! But we had the run of the place, before it opened to students in the summer. I found someone there to introduce me to weaving, and after that I bought a loom, which is now in my studio in New York City – my first weavings are now in a show at the Everson Museum called AbStranded: Fiber and Abstraction in Contemporary Art.

I actually started the ceramics some time ago, at Greenwich House Pottery in New York. That’s a very old institution in New York City, a place where serious artists and people from the local community exist side by side. My friend the painter Joanne Greenberg was the one who suggested I take a class there, and I met the artist Alice Mackler there. Alice is a wonderful artist, about to turn 90. She took classes there for something like 20 years, recently was discovered by the art world, and has been getting a lot of attention and finally selling her work. I like the idea that you never know when it’s going to come and when it’s going to be right. To not have a preconceived notion of certain things, but being open to the process. My life as an artist and my life in general – there has not been a plan. Life throws things in and you’re thinking: well, how can I make this work?

Does that mean, that you work spontaneously? The models of the exhibition rooms seemed more like someone very organized who likes to think ahead.

Yeah. But it’s organized chaos. I need to be somewhat structured. Sometimes it’s just the practical stuff – how many pieces of fabric do I need to cover 300 square meters of floor? And even if something is planned, that doesn’t mean that when I am actually in the space and working with the materials it doesn’t come out completely different. There are more rules than people realize, but I don’t think people have to see those. I have one side of my brain that’s totally chaotic and the other leads me to something that is more structured. And I like both.

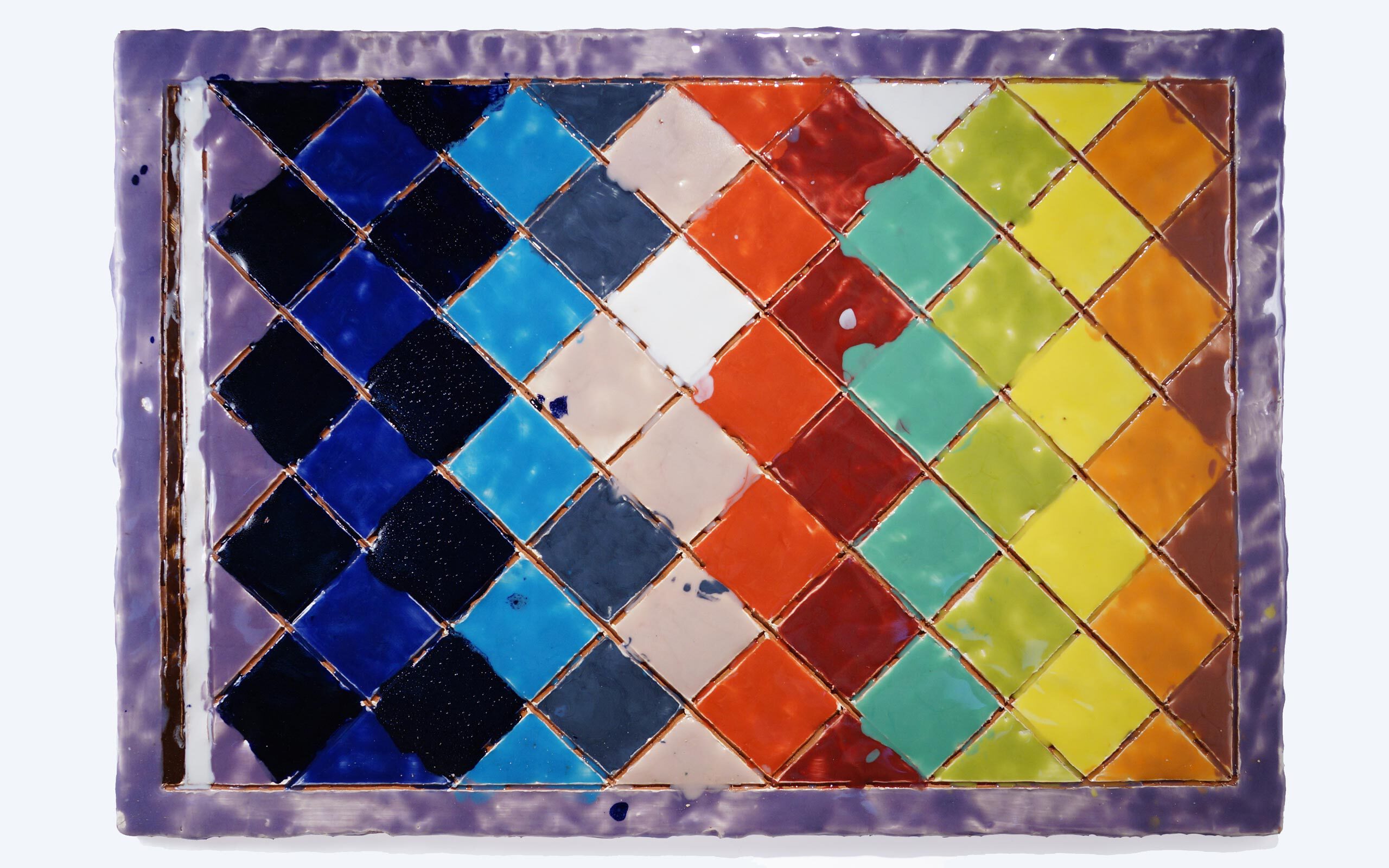

Pennsylvania Ellinger Quilt, courtesy of Frith Street Gallery, London, Galerie nächst St. Stephan, Vienna and the artist

Purple Fire, courtesy of Frith Street Gallery, London, Galerie nächst St. Stephan, Vienna and the artist

Is there a prejudice or misunderstanding concerning your art that is persistently prevalent?

It would be easy to list all the obstacles, but I don’t think you can be an artist if you think too much about the negatives. But I do look at an artist like Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and how difficult it was to fit her into some preconceived category. Not just the material and the “woman’s work” thing. It is working with abstraction and with a lot of different mediums. I don’t think art history likes that. And I think sometimes people want to think of me as an artist who works with fabric, or exclusively on the floor, but I don’t want to be confined in those categories either. It’s not just being contrary, there’s a method to the madness and there is a pleasure to just letting your mind wander, and see what you discover along the way. The imagination is not predictable. I don’t like to predict what I’m going to do and to be surprised.

You obviously like the process.

It’s true, I love to just see what can happen, and to keep the possibilities open. And that’s why nothing is fixed. I love that. I would come and I would throw the piece of fabric on the floor. And I had that connection. When I was young, I would pack up a box thousands of pieces of fabric and just unpack it in the space. And that was my studio. The gallery space was my studio. I taught myself installation. But I would say that as much as I like the process, its directed toward some kind of end product – something concrete and visible. So I am not a pure ‘process’ artist. I love things, real concrete things – in a way, I am trying to make real things that are not fixed and definitive.

Interview: Marie-Sophie Müller

Photos: Katharina Poblotzki