Nigerian-American artist and poet Precious Okoyomon envisions new worlds in their artistic practice, filled with nonhuman beings and invasive plants. In inviting audiences to participate in a collective dream, Okoyomon sets forth a simple yet profound condition: not to hide one's true self. With revealing questions, the visitor is confronted with parts of the self that were hidden before. This effort to figure out the ‘self’ is Okoyomon’s gift to others.

Precious, if you were asked to describe your art to a stranger, what would you say?

I would say that it's poetry that happens to be art.

As a child, did you imagine your future as an artist and a poet?

I didn’t think this would be my life path. As a child, I would always tell my parents that I wanted to do something that felt magical, though I wasn't sure what that would be. I was really into philosophers, a strong passion for pataphysics, which I later studied in college, and I was particularly obsessed with the French writer Alfred Jarry and existentialist thought. So, it wasn't surprising that I found myself pondering, “How do you make your life absurd magic every day?”

Was your family supportive of your interests?

Yes, they were as supportive as a Nigerian immigrant family can be.

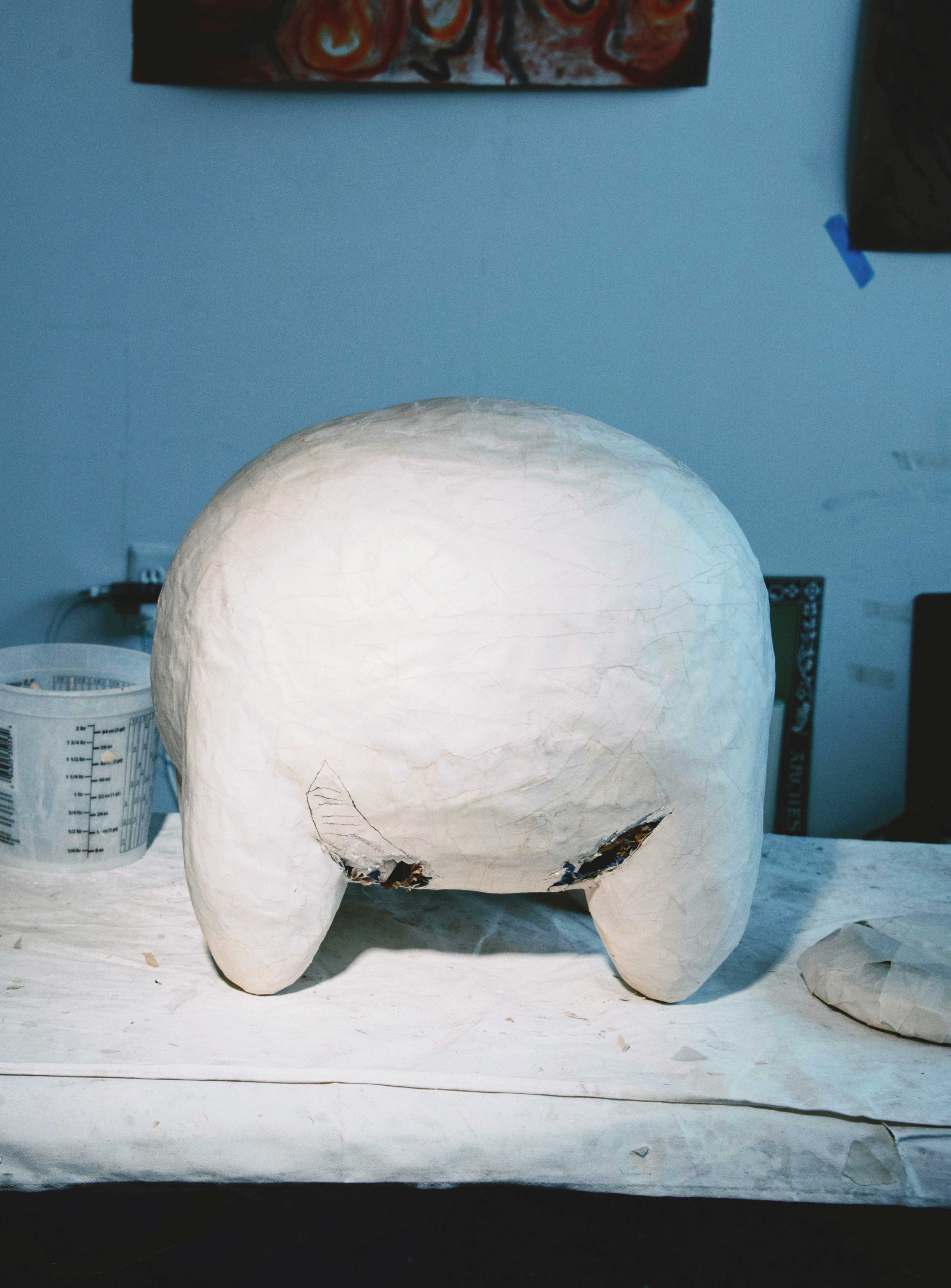

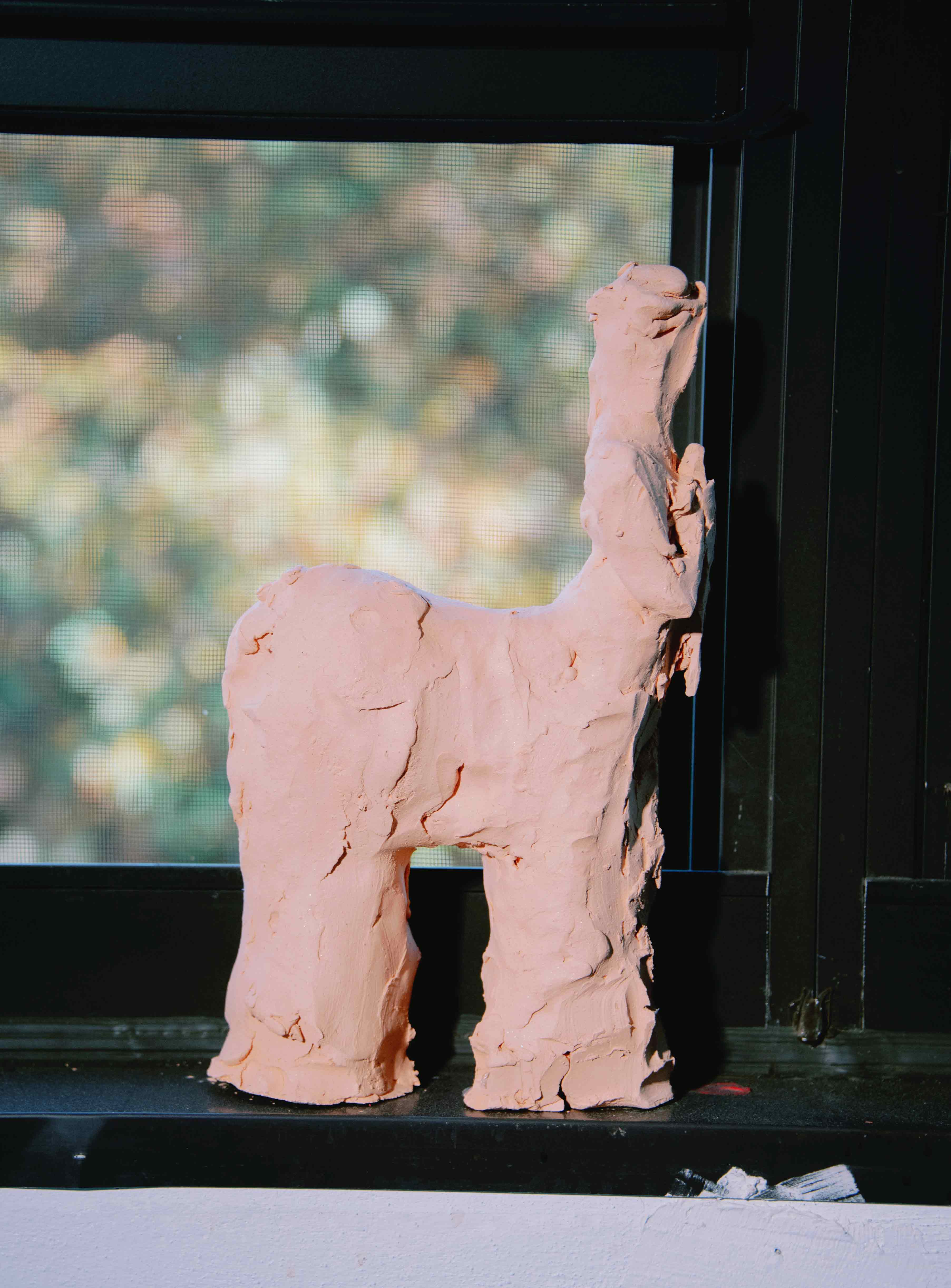

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

Dreams are a vital aspect of your art; what makes them meaningful to you?

Dreams are the basis of my practice and how I see the world. It is the collective dream we all decide to create together and how we navigate it, whether it is the world we want to see or the radical imagination we have together to imagine the possibilities of how we can make our world. This radical dreaming comes from a freedom of having a clear, narrow pathway and being able to understand the people around us.

Dreams are one of the topics featured in your large exhibition, “ONE EITHER LOVES ONESELF OR KNOWS ONESELF,” at Kunsthaus Bregenz, which spans several floors. Could you tell us more about the ideas behind this show?

The show is really about rituals – how I think through ritual, being with other people, and kind of making and unmaking the self. It is a big part of my practice, my poetics, and my general praxis. I do [psycho]analysis twice a week, that’s a huge ritual that I follow. I want to extend that type of care to other people who don’t necessarily have it in their lives. That’s why the show starts with my “existential detective agency”, which was a dream job of mine as a kid.

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

What does “existential detective agency” mean?

I created a fragment of an exhibition where you enter one of two houses and you become confronted with my questions. A stranger interviews you, and there are two rules: “I will not lie”, and “I will not hide the self”. You have to answer the questions honestly; this will give you the tools to go through the show. A lot of it is about fragilization – being able to break the self a little bit and to show somebody parts of you that you don't yet know. The expansion, the change, and the growth that comes with it is a miracle.

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

The questions begin with very basic inquiries, such as "Who are you?" and "Where did you come from?" These progress to more profound topics like "What did you leave unsaid?" and "Who caused your mother's suffering?" How do museum-goers react to such a conversation?

I'm receiving a lot of messages on Instagram from people saying, “I broke down; I haven't been able to even answer those questions; I took them home, and they've been sitting with me; These are things I've never given myself time for.” I am a strong Lacanian and practice Jungian psychoanalysis, but I believe that analysis isn't just meant for the office; it's a relation between people. If we changed our way of communicating and learned to share with others, we wouldn't need such a strong frame all the time. It's about trying to expand that frame – seeing others without a defensive eye to make space for this fragilization. This way, it comes up more naturally in our world. We can give each other the space to make room for ourselves in a true fashion.

Your artworks feature elements from childhood, such as teddy bears, hanging toys and hand-painted wallpapers. Why is this connection to childhood so important to you?

Childhood is the basis of where we all gather our understanding. It's a place of imagination, a source code that I go back to. I view it as this place of original fragility, but also as a place where also violence comes within cuteness, and how we are inexplicably changed during this time, how it transforms our lives. My childhood was interesting and tumultuous; yet it is a place that holds a lot of mystery and it’s actual. That is my root of love. It's filled with both beauty and darkness, but continuously working through that is a journey of knowing the self deeper and loving the self. The show at Kunsthaus Bregenz, for me, is an extension of what I can give people – a small fragment of a gift of making and unmaking, of understanding the self. This reworking and the effort to figure it out together with each other is truly a miracle for me.

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

Your installations often incorporate plants and beautiful gardens. When you create works that involve elements of nature, there is always the possibility that the objects will take on a life of their own and eventually change. How do you feel about losing control over your artworks?

I love when things are beyond my control. It's probably part of why I'm a poet and a gardener. In Bregenz, I wanted to trap the visitors in this little, beautiful, poisonous garden of my childhood. It's filled with many plants that I grew up with as well as those I fell in love with when I came to Austria, which were very similar to my childhood favourites. I visited Bregenz so often that I did a lot of seed saving. It felt nice to pick something and trace its origins. That's actually how I build a lot of my gardens: through deep research, finding something, wanting to know its history, cultivating it, and discovering the seed.

In the center of your installations, sugarcane and kudzu often played significant roles. For example, they were important elements in your show “To See the Earth Before the End of the World,” which was exhibited at the Venice Art Biennale in 2022. Why did you choose to focus on these particular plants?

Kudzu and sugarcane are two very special plants. Kudzu was brought to the U.S. after slavery to fortify erosion of local soil, which had been degraded by the over-cultivation of cotton, and then turned out to be uncontrollably invasive. It's one thing to solve the effects of the Transatlantic slave trade, and then there’s sugarcane, which actually funded and was the very bedrock of this trade. The histories of these two plants come together in this room, illustrating how they can create a world outside of our colonial mindset, transforming from perceived monstrosities into two very beautiful invasives with terrible histories.

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

What is the future of your gardens after the end of each show?

Every time I make a garden, the plants always go back to the community they came from. In Aspen, everything went back to community gardens and schools. In Venice, we burned all the invasive plants because they are invasive. The ash from them was used later for my show in New York. The sugar cane was returned to the farmers who sold it to us. Here in Bregenz, it's going back to the community as well. That's a big part of my practice: the things return to the place where they will be nurtured. The trees always get replanted because that relation is endless. It doesn't stop in the museum; it goes back into the place, and then the tree grows and becomes rooted.

You speak a great deal about collectivism – dreaming, resting, eating together. What role do relationships and community play in your creative process?

I never consented to being an individual. That’s my problem. I care deeply about people. My practice is the art that I love, but then there's love itself, which I am rooted in, and joy, and the things that nourish me. I always feel there is so much I want to create with the many people I love. I find myself frantically trying to do everything all at once, to crack all the things so it can spill over, and that’s when the most fun happens for me. Independent loneliness is not utopia for me; rather, utopia is about people coming together to make dreams happen. I’m a gardener, and no garden is made alone. At the same time, I deeply believe in my solitude, which is a big part of my life. Many of my poems are reflective memories of my time spent alone. I write poetry alone, but there’s a space for that; there's so much moving in and out of different realities for me.

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

You mentioned earlier that your practice is poetry, which happens to be art. Are these two media inextricably linked for you?

I don't see a separation between poetry and art; they are the same for me, leaking back and forth into each other. I believe in messes—sticky little messes. It's like a dream, the collective love together. As a kid, I always wrote poetry; it was my way of communicating with most people in my family. You'd know I had something serious to say when you received a long poetic letter from me. It became my way of understanding the world and learning how to communicate with people. That never really changed; it just morphed into new forms, like food and objects etc. It continuously transforms, but poetry is the root for me – an ever-going process.

One example of the intersection of poetry and art is your film “Skysong,” which was shown across from the garden at the exhibition at Kunsthaus Bregenz. In the film, you pilot a plane while reading your poetry aloud to the sky. When did you become a pilot?

I was flying over my hometown, Cincinnati, Ohio, where I grew up. It’s another fragment of my childhood, as I spent a good majority of my life there from ages 12 to 19. During that time, I constantly sought escape and sources of freedom. The sky became my escape. I learned to fly at a young age, around 16, when most people were getting their driver's licenses. The sky was the place where I found the most peace, allowing me to create a space for myself to feel free. In this exhibition, you find yourself trapped in my utopia, surrounded by butterflies that live and die within that space. Meanwhile, across from you, you can witness my freedom, but you're not allowed to access it.

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

Coming back to the exhibition title “ONE EITHER LOVES ONESELF OR KNOWS ONESELF.” At what stage are you currently in terms of loving yourself or knowing yourself?

It's a constant journey, honestly. It depends on the day. It oscillates between fully knowing and fully loving, but I'm never there. It's always the journey – you know yourself to love yourself deeper.

©Courtesy of the artist and ART Magazin, Photographer: Lila Barth

Interview: Anton Isiukov

Photos: Lila Barth