German artist Raphaela Vogel is known for her expansive installations as well as for her sculptural sound and video collages. She studied in Nuremberg and in Frankfurt am Main. She often works with found or transformed readymades and appears in her videos as a performer. Since the beginning of 2022, she has been living in a modernist house in the style of “Neues Bauen” in Berlin-Eichwalde, which was built in 1931 and has a special history inasmuch as a Jewish family was kept hidden there during World War II. In the garden of the house, she is currently developing a sculpture that references the building’s complicated past. In her interview with Collectors Agenda, she talked about her path to art, the importance of readymades, and her passion for architecture.

Raphaela, how did you get into art?

I got into art when I was 14 years old. I had a lot of friends who were involved with art, or the theater and I found it an inspiring environment. Some interest came from my parents, although I don’t come from a classically artistic family. Nevertheless, my mother had artistic talent, she painted, and also liked to decorate rooms and design the garden, she was also a master at creating atmospheres. I try to do the same in my studio. I always found it admirable how loving she was with everything. To this day, I love her wonderful watercolors.

You studied in Nuremberg and at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main?

Yes, I had applied to a few academies. In Berlin I was rejected but Nuremberg accepted me right away. The premises of the Nuremberg academy were great. Architecturally with its modernist, pavilion-like design it’s the most beautiful academy I’ve seen. It is here where my passion for and involvement with architecture began. However, already in the first semesters I realized that what I had come to know in my circle of friends and through theater people from Erlangen was more interesting than the discourses that took place at the university. As a result of this, I had a minor crisis and considered quitting or going to another university, I decided to enroll at Frankfurt. However, Nuremburg did have good aspects and further into my studies more conceptually oriented artists like Michael Hakimi and Michael Stevenson joined the academy and I tried out everything that was offered: painting, sculpture, I participated in many different workshops. It was an exceptional time, yet no one paid my work any attention and I began to ask myself whether I was really making art, or even whether I actually wanted to make art. The art business was for a long time foreign to me and ultimately it was in Frankfurt where I discovered contemporary art and its potential.

Why did you ask yourself these questions?

I knew art through a preoccupation with myself and I always missed the interesting scenes in Nuremberg. It was only in Frankfurt and Amsterdam that I felt a sense of integration into the existing art scene. It was in those cities that I was quickly able to stage solo exhibitions. In parallel to my studies, I was able to exhibit at the Bonner Kunstverein, also at that time I began to exhibit in large spaces, that is a challenge of course, but in Nuremberg I had learned to work in terms of space and I still do so today.

Acting plays an important role in your installations and video works, how did it come about that it became an integral aspect in your range of media?

I don’t really know if I’m acting because it’s often an in-between thing for me. In my works, the recording devices determine an action, for example drones or cameras. I’m always in control of what I do in these video works, in part because I like to work alone, without cameramen or assistants. Then I’m mostly in an “in-between moment,” between playing and doing things. I’m driven by the question of what the role is I’m taking on in a situation. It derives a bit from the fact that I’m inspired by filmmakers like Adriano Celentano, who develop the entire making of their films from the perspective of one person. They are the actors in their films, they write the script themselves, they direct and shape the entire work of art themselves

In your videos and here in your studio you work with readymades, why?

I wouldn’t use the term readymade, because it’s too suggestive of Duchamp’s concept, which is central to the idea of the found object. There are different strands in my work. The molding of found objects is one of them, and the found objects themselves, sculptures, models, and then there are the connecting elements, the trusses, the poles, the leather work, as can be seen here in the studio. They all have a function within the artistic process. Art for me is that process. It’s a framework of technique, of elements, craft, and possibilities. An ontology inherent in the object, and the meaning it conveys. A found object brings with it many narratives, not least the work of others that created the object in the first place.

Do you also consider your studio a large found object?

Yes definitely! But a very special one. This house has become an actor for me in my art because it is a special place. I didn’t choose this tragic and intense story – in the sense that I chose the house because it’s an interesting studio with a troubled past. I became aware of all this gradually during the renovations. A Jewish family was hidden here from the National Socialists for three years, a story that I then dealt with in detail, and it is very upsetting, even though to a certain extent it can be said to have ended well.

How did you find an approach to this charged place?

I have dealt intensively with the past and the biographical fragments and want to commemorate those involved with new works. Altogether, this has given me a new approach to my studio. But that is the case anyway: The architecture and its history determine my work and thus become an exhibition object themselves. For example, I once hung two heavy bronze lions from the ceiling, which the structure of the building could only just withstand. I conceive works based on the external structural form of the house. The studio itself becomes a trigger of works. Not that you go into the studio and produce, but that its architectural conditions trigger something in me and are thereby productive themselves. That this is the place that triggers other works of mine.

And how did you come across the studio in this location?

When I was pregnant, I wanted to get out of my Berlin apartment. I wanted something new that was more on the outskirts of town, because I grew up in a house with a big garden myself. I made the decision to move out because I didn’t want to outsource childcare. And it’s just easier in a house in the countryside. I also have a dog here. So, there were many reasons for me to move to the countryside because a studio, life with the child and with the animals can be better combined on the outskirts of the city. I spent a long time looking for a suitable place. Also, because I might not want to live in the city later. And that’s why it had to be something where you realize that more can unfold there than just a normal life in a functional building.

And why did you choose this house?

It has an interesting history within modernist architecture which has not been uncovered in the last sixty years. In the former GDR, the house had not been painted and renovated in accordance with the preservation laws and regulations. In the 1990s, it was listed as a historical monument, which made it our task to undertake any work on the building in such a way that its architectural integrity would not be compromised. We had to develop the earlier design and the color typology in a contemporary way, but we also had to meet the requirements for the preservation of historical monuments – an intensive occupation that has led to the fact that it is now more than just a house for living or simply a studio. This building is fusing with my own art.

You often interact with architecture in your work. How did that come about?

I don’t know. Maybe because I grew up in an interesting architectural environment. We had a ceilingless house where everything was under one roof. I’ve always had an interest in planning, as a child I built rabbit hutches. I’m a little obsessive with architecture. I don’t know how that came about. It’s just this kind of pursuit. And my art needs space and the architecture as reference points.

What was the most important exhibition in your life?

I would make a distinction between exhibitions that promoted my career and less significant shows that were important to me personally. My first institutional solo show at the Bonner Kunstverein was a hybrid, to which Oriane Durand had invited me. At the time I was still a student, and she just invited and trusted me! Although only a few people came to see the show, it was an important step for me. On the other hand, my exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel during the Art Basel where the whole world came received a lot of publicity, and I had a solo presentation in the large rooms of the Kunsthalle. That was a moment of magnification, of scaling.

What did you show in this exhibition?

The exhibition was called Ultranackt (ultra-nude). In the show, I chose the myth of Marsyas and related it to the symbolism of the ‘ultras’, fanatical soccer supporters. It is such an abstract power symbolizing strength, as in the case of the mortal Marsyas, who was flayed alive because he had the presumption to challenge the god of music, Apollo, to a music contest. The entire theme of hubris in making art is summarized in a condensed way. I continued this motif from ancient mythology with Arachne, who challenged Athena to a contest in weaving. In the competition there lay again the motif of hubris. I have linked this mythological concept with the architectural idea of the spider’s web.

So again, an architectural basis?

I have worked with horizontality in many exhibitions – a structural principle that also derives from the spider, a kind of eight-legged interconnection of elements. In the Basel exhibition, I designed many works on the principle of verticality – a rising horse transforms from space to space: first into Brâncusi-like columns and then into a huge stromi-solator. Next January there is an important exhibition in Tilburg. The biggest retrospective exhibition I’ve ever had in a museum. And there are a lot of works coming together that I haven’t been able to bring together like that. It’s interesting to encounter my own work through new combinations.

And what exhibitions do you still have coming up?

The exhibition KRAAAN at Museum De Pont in Tilburg, Netherlands. In Dutch you write crane with two A’s. And I have spelled it with three A’s, because the machine called a crane has many ‘A’ forms in its physical structure. In this work which I created last year a crane is at its center. It’s a film in which I climb up a crane with a 360-degree camera. The film refers to a 1981 video by Helke Sander, who filmed a mother with her two children climbing a crane to its horizontal boom. When she reaches that point, the woman releases flyers that read, “If I haven’t found an affordable apartment by the evening, I’ll jump down with the two kids.” In it, she addresses the housing emergency and the social situation of many single mothers. I referred to this impressive work with a video piece and interpreted her film in an architecture model. And we show other Helke Sander films as part of the exhibition and a crane work by my friend Christoph Dreher, who made a film in the 1980s. You can see the Kotti in Kreuzberg from above. The exhibition is about urban development, the crane as a capitalist symbol, as a metaphor for change and how a city can transform itself. In addition, my work Können und Müssen, which I developed in 2022, is currently being shown at the Venice Biennale in the Arsenale exhibition space. It is a multi-part sculpture. A penis with a corpus cavernosum implant, which is simultaneously affected by testicular and prostate cancer, is pulled by several giraffes. It is about the question of masculinity, patriarchal identity, and this “always have to”.

What projects are you working on right now?

What you can see in the garden: an outdoor sculpture for the Kunstverein am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz in Berlin, for the Gallery Weekend next year. I want to do something about the Jewish history of this building and Berlin for that. I was thinking of creating a kind of “Memorial.” It will be entitled Memorial Structure: Elephant Memory, and its structure will resemble a historic pavilion from the south of France in 1880. And that structure will bear cast-off elephants – ten in all. Elephants are known to have a good memory. That’s why for me they are the symbolic animal for memory work.

Who are you thinking about?

At Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz I want to remember Roberto Burle Marx, the German-Jewish-Brazilian artist, gardener, urban planner, and architect. A Brazilian modernist, who in the 1990s made a design for the square and wanted to radically redesign it. And this square design was never realized, although he was famous in Brazil, for example for the legendary wavy line on the Copacabana promenade. It was too crazy, too wild for Berlin. I will take up this design in the artwork. At the same time, I also wanted to take other designs of his as an opportunity to develop new paintings. And these paintings will then hang in this pavilion. That is the first place of the journey.

What is the second location?

My House. The unifying element is that both stories have a Jewish background. The Scheunenviertel in Berlin-Mitte was also a predominantly Jewish neighborhood. I also read the reports about the former residents of our house, and much of what happened in this area of Berlin reminded me of these accounts. One of the residents who had survived here, later also stayed in the Scheunenviertel. The installation then travels on to a synagogue in France, to which I was once invited a few years ago. That has since become an art gallery. At first, I was unsure whether I should do an exhibition there, because I didn’t want to completely ignore the context of the synagogue, and at the same time I didn’t really have any relationship to the subject matter. And now this linking of the biography of Roberto Burle Marx and the story of the writer Erich Hopp’s family, who survived in our house, fits very well, and everything corresponds with the memorial structure.

Do you know more about the family who lived in the house?

Not so much is known. Erich Hopp, who was kept in hiding here for three years with his son and wife and survived, was a theater maker and poet. He was a multifaceted intellectual in Berlin. In 1931, the year our house was built, he wrote a tango together with Miss Germany, who was also Jewish. The tango was published by a Jewish publishing house and was called Jede Frau ist schön. So, it’s a totally feminist tango. And I digitized this tango and played it with musical instruments. It is performed in the installation. And the installation has many elements that are fixed – the elephants, the water jet, the fountain and the reinterpretation of Marx’s garden pictures. That’s why I’m also dealing a lot with plant and garden theory. The house will continue to play an important role in my work in the future. I can already feel that.

Raphaela Vogel, Mogst mi du ned, mog i di, 2014, Chromed metal rods, flamingo (plastic, metal), Nesquik can, plastic foil, 2 loudspeakers, video projector, Mac Mini, audio and video cables, base, video (color, sound, 6:25 min., loop), exhibition view: Raphaela Vogel, Raphaela und der große Kunstverein, Bonner Kunstverein, 2015, photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne, Courtesy BQ, Berlin and Raphaela Vogel

Raphaela Vogel, In festen Händen, 2016, two bronze sculptures, two steel rings, two heavy-duty belts, two-strand chain suspension, swivel hook, amplifier, two spherical speakers, i-Pod, cable, sound recording (2:56 min.), Exhibition view: Raphaela Vogel, In festen Händen, riesa efau - Motorenhalle, Dresden, 2016, Photo: Werner Lieberknecht, Dresden, Courtesy BQ, Berlin and Raphaela Vogel

Raphaela Vogel, Können und Müssen, 2022, Courtesy Galerie Meyer Kainer, Photographer: Kati Göttfried

Interview: Kevin Hanscke

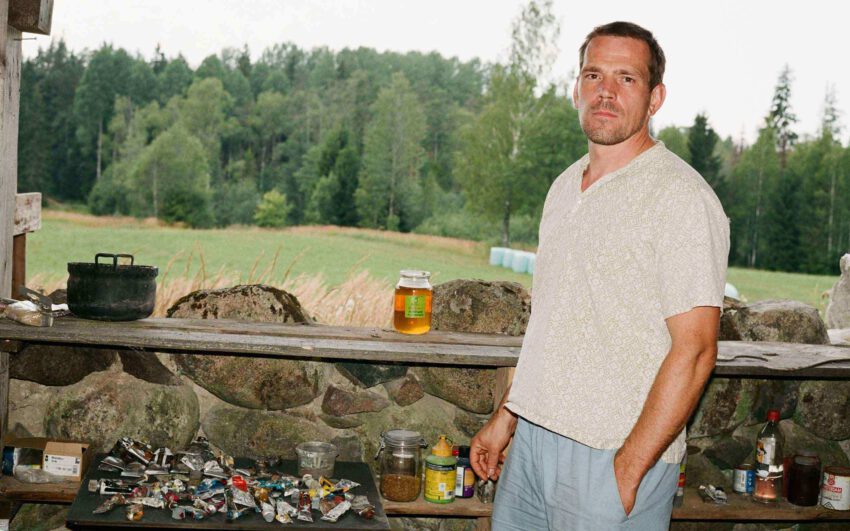

Photos: Nora Heinisch