In his work, Samuel Henne examines different structural stages in the creation of images on the basis of the interplay between sculpture and photography. Artistically, mechanisms are questioned that Henne also uses himself to create new images. The works are often created in serially arranged working complexes. A certain tendency towards perfectionism and the setting of color accents give the works a pop-cultural quality.

Samuel, in your creative process, three aspects: space, sculpture, and photography are placed in relation to each other and specifically questioned. How did these focal points develop in your work?

Initially, I focused on the moving image, i.e. on film, although some early cinematic works already had something static about them and raised questions about space and the cinematic or even pictorial movement. I began to take an interest in the construction of pictorial-scenic moments and the staging of still lifes and images in general, and to question the mechanisms and their associated production. Again and again I was interested in finding out where the limits of photographic images lie and how they can be exploited.

What exactly does this approach to the implementation of your work look like?

In my work, for example, I examine staging structures that also affect my own pictorial genesis, and question and address the process and meaning of these mechanisms, among other things in relation to a final artistic work. Over time, photography has become my preferred medium for investigating these questions, as it allows me to create connections - i.e. links to other media such as sculpture or painting. Over the years, space has repeatedly become an important component in these processes of questioning, since it and the further levels it evokes allow me to test and examine the complexity of views and settings in different ways, in a different and expanded way.

Your works require partly elaborate staging. Can you describe this process of image creation in more detail?

My work process can be perceived in terms of my ultimate goal, which is to construct new images. This usually takes place in a working context, which in the end deals with a certain theme or serial “processing” of an idea, which can thus be called “serial” in the broadest sense. In the course of the conception and the elaboration there is certainly a certain tendency towards perfectionism. This is especially true for the control and influence of the imaging parameters. Most of the time, every detail is planned and thought through exactly and ultimately carried out in this way. Nevertheless, I am aware that from time to time it is necessary to be less of a perfectionist and to allow or grant a certain spontaneity a certain leeway.

Do problems arise from time to time, as a result of this, as you say, perfectionistic approach?

There are always surprises in the work process and a one-to-one implementation from conception and design to the final realization always includes certain aspects that ultimately cannot be anticipated a hundred percent in advance. Basically, there are quite a number of pictures that do not work as planned for me and thus lose their “validity”. Concretely, this can happen even if a picture has been worked on over weeks in the studio, and repeatedly adjusted and “checked.” Yet I may in the end, decide that the whole thing must be discarded, and then one basically has to start over again.

An exciting aspect of your work is the way you take up the spatial component.

The aspect of the spatial is for me, among other things, always the attempt to “move around” the object with photography. If photography as a medium attempts to represent a sculpture, this is for me an assertion in the sense that a single image initially says relatively little about a three-dimensional, spatial object context. I therefore find this assertion of decades of “sculpture photography” interesting, but also questionable. The work musée imaginaire (2013), for example, deals with related aspects in concrete terms. Within the work, I have in turn transformed publications with photographic images of sculptural works into sculptural objects myself and photographed them in the studio in such a way that a certain spatiality and three-dimensionality is evoked and a “trompe-l'œil effect” is created, which, despite the size of the images, initially suggests spatiality and objecthood.

For the work musée imaginaire you used certain books containing historico-sculptural illustrations. What is your particular interest in these publications and their depictions of sculpture?

The publications on which the work as material was based were a means of disseminating views of sculpture at the time of their appearance, i.e., from the 1920s to the 1970s. But they also determined how sculpture was received in an art historical context and were a major basis for writing about sculpture. For me, this aspect has always been fraught with a certain questionability regarding the actual meaning or even the possibility of reproducing a three-dimensional sculpture through photography. I always found this inherent assertion of the “depictive”, as well as treatises on how sculpture should be photographed, interesting, but also questionable, because in this context of photography and sculpture, not only the strengths, but also the clear shortcomings of photography can be seen very clearly at the same time.

Can you explain your artistic perspective regarding your questioning of the art historical references relating to musée imaginaire?

In dealing with the books I began to pursue a “breaking of the images” by folding and folding the pages. This resulted in “new constructions” and collages that allowed a critical questioning. It is also interesting that the questioning of the depiction of one's own works was already apparently present with artists like Constantin Brâncuși, who wanted only his own photographs of the sculptures to be circulated, since for him they represented “his own works”, and were intended to reflect the essence of the sculptures on a sensitive level. He thus spoke out against a purely photographic “reproduction”. Auguste Rodin on the other hand, was more strategically interested in photography in the sense of media dissemination. These different aspects of the very early connection between sculpture and photography in the work of various artists were a starting point for my interest in collecting and the selection of books.

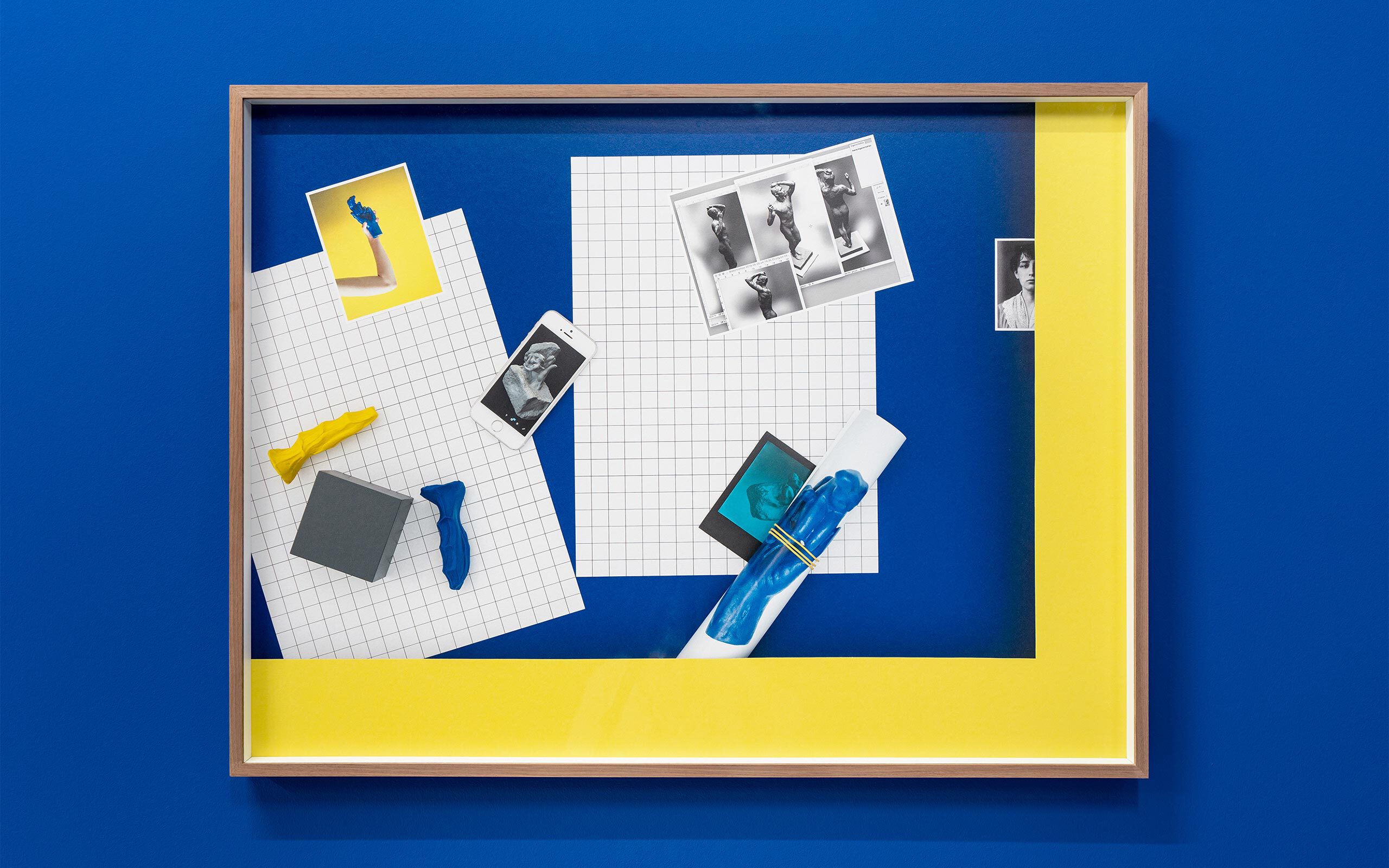

You just mentioned Auguste Rodin. You have also repeatedly dealt with his work in your exhibition “shifts & tilts” (2019) within the work series hand to hand (2019-2020). What can you tell us about it?

Rodin served as my starting point in the context of the work hand to hand (2019-2020). In an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, I encountered the hand sculpture The Hand of God (1896-1902), which is attributed to him. After some initial research, various questions and considerations regarding copy, original and authorship came to mind, which are found and negotiated on various levels and strands within the work. The hand sculpture shows a cast of Rodin's hand, not a “sculpture” in the true sense of the word. It holds a female torso, which in fact was formed by Rodin himself, and thus this combination results in a kind of “mash-up”. Nevertheless, the sculpture is distinguished as the work of Rodin, although it is actually a cast of his hand made by an assistant. The thematic, masculine myth of the creator and the assertion of the “original” thus deconstruct themselves in a certain way, which I found a remarkable twist in relation to Rodin's questionable persona.

This remarkable twist then led you to the work entitled untitled (Bronze age no more) (2019).

I purchased a bronze copy of the hand sculpture, inscribed “after Rodin”, from an online art dealer, and so another aspect was added to the confusion of attributions. To negate the pseudo patinated bronze, I used a dark blue plastic spray in a gesture of appropriation and to comment on the bronze’s swan song. The appropriated result is quite “tacky” and artificial and was subsequently placed by me in a female hand within various pictorial stagings. The work untitled (Bronze age no more) (2019) thus wants to remove the the element of patriarchal, godlike creator-claim from the sculpture in a certain way. This aspect is also linked to the assumption that Camille Claudel worked very concretely on various sculptures by Rodin, and thus there are indications that she not only strongly influenced his work, but also contributed to it technically – “manually”, i.e. “in a hands on capacity”. In the context of original and attribution, this was for me another exciting additional level that resonates quiescently.

In the case of exhibitions, you consciously work on the color of the exhibition rooms. What is the purpose of this additional artistic intervention?

With the intervention and the settings through the wall paint within the exhibition rooms in which the works are shown, one of my aims is to make a leap from the pictorial space of the frame into the factual space. On the one hand, I play with finding out how the spatial and color interventions influence the paintings and whether this negates something or creates a new, unique relationship between space, pictorial space and work, which I would affirm in most cases. A kind of correspondence between pictorial space and exterior space can emerge. On the other hand, I am also interested in questioning museum settings – in other words, critically pursuing the idea of the built space for art and its staging by using similar strategies and referring to them. For it cannot be denied, of course, that such settings, whether within a museum or a gallery exhibition, bring with them a certain dominance and can be a staging that one could perhaps critically describe as “too pleasing” or “eye candy”. Nevertheless, this also repeatedly raises the question: “What is it that is actually brought together there?”

As a collector, if I wanted to buy your works, would I have to have my walls painted or changed by you to give the work a more complete character?

No, basically the interventions in the wall designs form, as already mentioned, an additional level which, for example, also “contracts” certain aspects within the exhibitions. In the exhibitions, my aim is, among other things, to try out and sound out the spatial interactions that can arise for the pictures. Otherwise, however, the pictures stand for themselves and are not necessarily dependent on the wall designs, but can enter into this extended dialog. But this is not absolutely necessary for a collection. However, I could, of course, on specific request, think individually about the walls of a collector and include and work on them accordingly.

Today, art is still digitally documented photographically and widely distributed via the Internet. An inevitable process if I want to be able to see exhibitions worldwide. Where do you see critical points in this dissemination of exhibitions?

As with the “shortcomings” of photography, in its attempts to depict three-dimensional objects such as sculpture, it naturally becomes apparent in this context that here too, sensually and in relation to any perception of space, various factors arise that cannot be compared with a real visit to an exhibition. In this context, the question simply arises again as to what photography can actually achieve, and here I am very skeptical about the “real reproduction” of an exhibition. In the photographic documentation of a sculpture or even an entire exhibition, the physical and spatial aspect will always be absent, including the individual's own relationship to art. An overall experience is not possible, and one has not actually experienced the exhibition, but rather viewed images of it. But apart from that, I think that any kind of “accessibility” and democratization is an added value in this respect, because you enjoy at least a degree of participation, even if you can't physically be in Manhattan or Basel at that moment.

We meet here at CCA - Centro Cultural Andratx on Mallorca, a rather unusual place for an artist residency. What brought you here?

Before I came here, I spent a year in New York for my residency at the ISCP - International Studio & Curatorial Program in Brooklyn. The residency here in Mallorca seemed like a good and meaningful counterpoint to this, and I wanted to spend some time in a place that was a little more cut off from the urban, noisy and hectic life. I found exactly that here. Moreover, the CCA is a renowned and well-known place that I absolutely wanted to experience.

untitled (HOG #01 - #04), from "hand to hand", 2019

polaroids with passepartouts

Exhibition view: „Samuel Henne - shifts & tilts“, Kunstverein Göttingen, 2019

Photo: Samuel Henne

Courtesy Samuel Henne and gallery FeldbuschWiesnerRudolph, Berlin

musée imaginaire, 2013

Fine Art Prints

Exhibition views: „Samuel Henne - Formations", Kunstverein Hannover, 2013

Photo: Samuel Henne

Courtesy Samuel Henne and gallery FeldbuschWiesnerRudolph, Berlin

hand to hand, 2019, Fine Art Prints framed,

Exhibition view: „Samuel Henne - shifts & tilts“, Kunstverein Göttingen, 2019

Photo: Samuel Henne

Courtesy Samuel Henne and gallery FeldbuschWiesnerRudolph, Berlin

untitled (constituents #01), aus "hand to hand", 2019

Fine Art Print

Exhibition view: „Samuel Henne - shifts & tilts“, Kunstverein Göttingen, 2019

Photo: Samuel Henne

Courtesy Samuel Henne and gallery FeldbuschWiesnerRudolph, Berlin

Interview: Alexandra-Maria Toth

Photos: Volker Crone