In his diverse artistic practice, which includes performance, sculpture, installation, painting, and video works, Simon Fujiwara deals with concepts of contemporary individuality in which the preoccupation with self-representation in social media plays a central role. Early on, his works were shown internationally, including at the Venice Biennale, the São Paulo and Gwangju Biennials, and the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. We spoke with him about his artistic path, about the obsession with attention and the role of the artist in a world that has become increasingly digitalized.

Simon, before you studied art, you received a B.A. in Architecture from Cambridge University. Why did you first choose architecture?

I never wanted to be an architect, I always wanted to be an artist. But before going to art school, I wanted to learn something else in depth first, so I studied architecture to learn about the world. I loved learning about the constraints within architecture – where ideas, ideologies, and thinking meet pragmatism and construction requirements. That laid the groundwork for my art.

You then enrolled at the Städelschule in Frankfurt. How did that happen?

I moved to Berlin first. I initially had no plan to go to an art school. I just wanted to start making art. I realized that I didn’t know any other artists of my age and generation and the way I was thinking about art was not reflected in the older generation of artists I knew. I wanted to have a dialogue with people doing what I was doing. But when I went to the Städelschule, I was not really accepted as an artist immediately because I had come from a school of architecture. I remember that I made a work for my first “Rundgang” that got a lot of attention. It was very simple. I emptied my studio, then the replumbed the sink so it overflowed with milk. It was like a sexualized fountain that became sour over the four days it was in place. It was well received but I overheard people saying that “he’s really an architect, not an artist.” I was disillusioned at first, because I was so excited to finally be making art and I realized I had stepped into a different world of containing its own constraints – the art world – where biography is often foregrounded. My own identity as an artist had been overshadowed by my past, I found this very frustrating.

How did you deal with this situation?

Back in 2008, the notion of self-determination or self-identifying that is now the norm was emerging with relatively new social media interfaces such as Facebook. People were beginning to realize the potential of the ability to manipulate their image and therefore their self-perception. I sensed that this was something both exciting and disconcerting and I was inspired by these social trends to tell my own story by means of advanced affirmation. So, the next work was an architectural project called “The Museum of Incest” that explored in depth my relationship to architecture. The museum was just a proposal and was not intended to be realized, but I treated it seriously, thinking about every detail even down to the museum cleaning staff. It was very personal and unquestionably architectural, yet ironically, it was the first artwork that brought about acceptance of me as an artist by my peers.

Your art is very diverse, your practice is both performative and interdisciplinary. You combine various disciplines and media in your work. How would you describe the art you make in your own words?

I never begin with the question of what medium will be, but rather what it is that I want to explore and how best to communicate that, then the issue of media comes into consideration. My work is visually all over the place and inhabits many aesthetics as a consequence of being made in the world now, where ‘collage-like’ and often colliding aesthetics are normal not just in art, or online but in everyday life. This can be about the material world we inhabit and the collage of values they embody – luxury meets the recycled/sustainable, information or news is presented as entertainment etc. There is more diversity, our digital encounters are more global, on any given day we are confronted with the possibility of multiple realities which was not the case even as recently as a decade ago. This is how my world looks – diverse, confusing, exciting, incomprehensible, fearful – and I can only make work that is close to my experience. It’s not a conceptual approach.

In Instagram account you write as an intro: “History repeats itself first as tragedy, secondly as farce, and finally as porn.” What is this statement about?

What do you think it is about? (laughs)

…Well…

I’m toying with the proposition of a ‘post-meaning world’, what it means to be alive in a time where received meaning in the form of religion, gender, politics, etc., has dissolved revealing its shortcomings to a point where it is relegated to nostalgia, cultism, caricature, etc. And then, from that, how we construct meaning for ourselves now, amid those ruins. Throughout everything we haven’t lost a desire for meaning or belonging but maybe in a ‘post-meaning’ world we can still have a meaningful existence. I’m trying to understand if this is possible or if the search for it is meaningless. I enjoy exploring this question so much that in itself it gives my life meaning.

How does this reflection on meaning manifest itself in your work?

Sometimes I look at things that are very significant and demand a lot of public attention but are considered meaningless. What is the status of the international bestseller Fifty Shades of Grey? Everyone seems to know it but nobody you know has read it, yet everyone has an opinion about it, that it’s tacky, stupid and, yes, meaningless! But the meaning is not only between the pages of the book, it might be in the social image it creates or the money it has generated or the social attitudes it embodies. It sold over 100 million copies worldwide. Can we ignore this? If we think this book is stupid and meaningless, are we also damning the 100 million readers around the world who have read it, loved it, and have learned something from it? Is this attitude a reflection of an internalized disgust for the masses? Is that democratic thinking? And so on…

It sounds as if you see yourself as a political artist, do I understand that correctly?

I feel very responsible to my time and work as clear-sightedly as I can to record, document, transform, mirror, or distort it. You can call it political if you like, I don’t care so much for that terminology. My primary care is people. I care deeply about the audience.

Does this also apply to your work on Anne Frank? You rebuilt the Anne Frank house and staged her, in another work that you showed at the Hamburger Bahnhof in the exhibition of nominees for the National Gallery Prize, you installed her as a media star. Isn’t that political?

I think I am much more romantic than that – I believe in some idea of justice although I don’t think I could even explain to you what that feeling is. When I was working with Anne Frank I was making several discoveries through going to the House in Amsterdam or producing a wax figure of her etc. That shook my reality and made me realize that for my whole life I had not been seeing her accurately, but only as a symbol or icon. There is a deep injustice and violence to how we perceive each other through the media. Anne Frank is a shining example.

I started making a whole series of work about Anne Frank that address a larger question of what humans do to other humans when they represent them. Anne Frank is an extreme version because she is such a representative human, pure, unflawed, innocent, intelligent, beautiful, and her story is deeply tragic. But I wanted to explore the fallout of when society congregates and forms meaning around a single person, what we do in our acts of extreme love. It is much more interesting to me to see how not only hatred but love can reveal our shortcomings and perversities as humans.

Do people ever ask you if you just want to provoke with your art?

Sometimes people ask why I work so much with pop icons and I respond: “Why did Cezanne paint apples?” Anne Frank, for example, is so famous, she has become almost invisible, or part of our habitat like a tree, a dishwasher, or an apple.

In your artistic work you have dealt with the biographies of other women, too, like Marie Antoinette, your former teacher Joanne, and Angela Merkel. Is there something that connects these works in addition to the fact that they are all about women?

I’m obviously obsessed with women. I could give you a pop psychology answer like “I was raised by a single mother or I’m gay.” That would be the easy answer. Historically, women have occupied a more interesting position than men for me because they have had to fight to change their status from object or property to human beings with their own rights. In this fight they have revealed so much about humanity. It interests me because now, through social media, many humans are willingly re-objectifying themselves again by seeking to become brands in their own right and therefore become tradeable, consumable commodities. When once a child would dream of being an astronaut, now some dream of being an influencer. I can totally understand that desire, where the everyday actions in one’s life from drinking a coffee at a café to meeting friends can become marketable experiences and therefore have some kind of meaning, through capitalist benefits or in the act of documenting and affirming one’s life experience.

How is it for you personally, as a famous artist, to deal with the “brand” Simon Fujiwara? Does this question play a role in your everyday life and your work?

I always think how can I resist being consumed. My work doesn’t follow a branding mechanism strongly, so it’s unlikely. It is hard to recognize “my work”. You can go to five different shows and you think they were made by five different artists. When you start to know my work, of course you start to know it when you see it, but sometimes people ask me “what the hell are you doing now?” I think I have a deep fear of self-iconizing. I don’t want to be in a situation where I have to follow a narrative that has been written for me – by myself of all people! I don’t want to become a caricature, but I realize I can’t totally control that either.

I can imagine that this is not always easy, especially because you work with some very famous galleries. Do you feel pressured by them or the art market?

No, because the simple answer is that I’m not interested in making anything if I’m not totally obsessed with it. That is the only time I make something and it is the only time that something is good. The people that I work with Dvir Gallery, Esther Schipper, or Taro Nasu, know that and the other artists they represent are also often inspiring. I work with people that still believe in art and in experience.

Do you think your work today has changed since, say, the Städelschule days?

It has become more sophisticated in many ways, I’m more confident but also more curious and, as can come with age, more in doubt about everything. Before I was working with a lot of text and images, it was more didactic, although intentionally so. But I will say in the first works I made are the seeds of every work I’ve ever made since. And that is bizarre to me, because every time I start a thread of thinking for a work I feel like I am in great danger, in unchartered territory, and I feel excited and nervous. And then later I see the same concerns repeating and evolving from other forms, and I realize how delusional I am. But then I am comforted by the fact that being alive is a delusional idea in itself. Art is the delusion I chose and in embracing its absurdity and being able to speak it out loud, it’s a world that makes a lot more sense to me than many others.

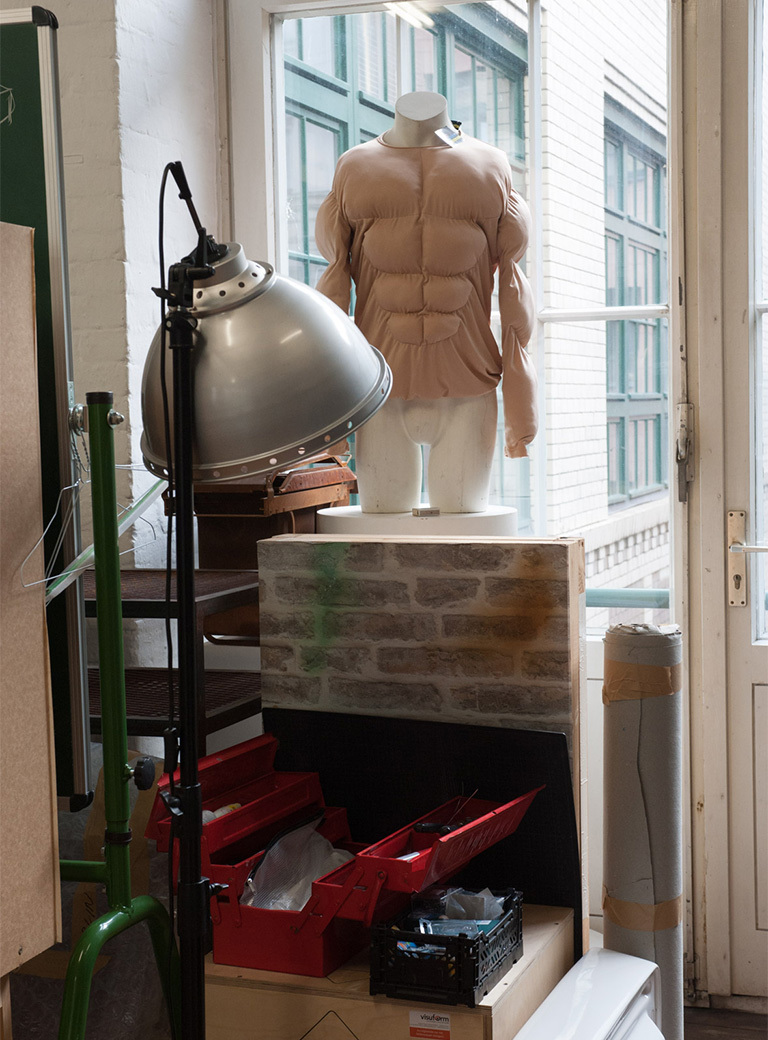

Fifty Shades Archive, 2017 – ongoing

Exhibition view: Preis der Nationalgalerie, Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, 2019

Courtesy the artist; Dvir Gallery, Brussels & Tel Aviv; Gió Marconi, Milan; TARO NASU, Tokyo; Esther Schipper, Berlin

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

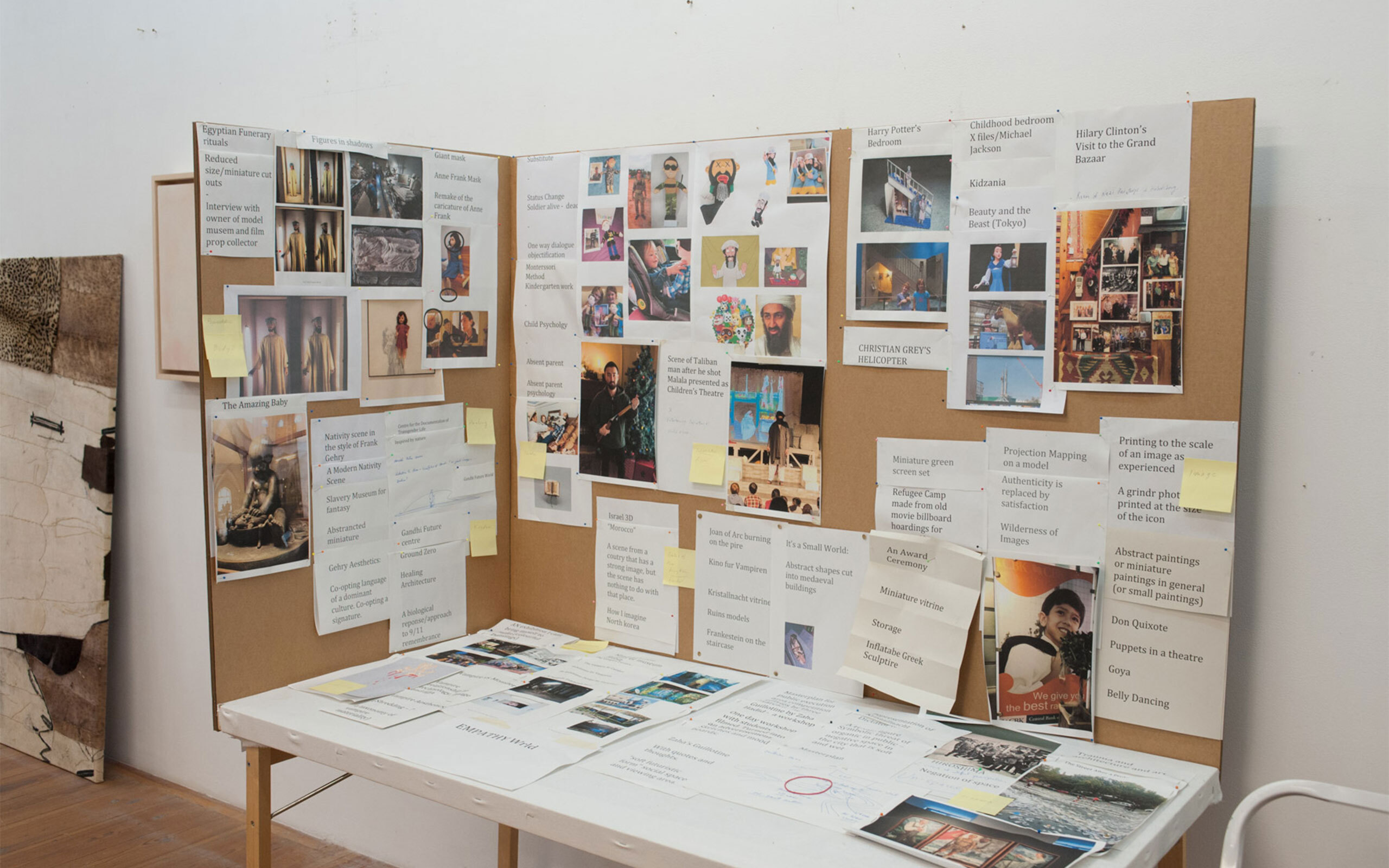

Exhibition view: Hope House, Kunsthaus

Bregenz, 2018

Courtesy the artist; Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz;

Esther Schipper, Berlin

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

Likeness, 2018

Wax sculpture, vintage desk, chair, lamp and objects, handrail, two-channel video (4K, color, sound)

Joanne, 2016/2018

Three free-standing aluminium-clad structures: one with in-built LED monitors screening video (duration 12:06 min) and digital print, two lightboxes with digital prints on foil.

Commissioned by FVU, The Photographers’ Gallery and Ishikawa Foundation

Supported by Arts Council England

Exhibition view: Simon Fujiwara, Joanne, ARKEN Museum of Modern Art, Ishøj, 2019

Courtesy the artist; FVU, The Photographers’ Gallery; Ishikawa Foundation; and Esther Schipper, Berlin

Photo © David Stjernholm

Interview: Dr. Sylvia Metz

Photos: Kristin Loschert