Simon Lehner’s themes are personal and collective identities, and how we form them by using our memory as a starting point. His first success was related to photography, but he now creates hybrid works that have painterly and sculptural elements. Through these, Lehner questions how we are being shaped by the flood of images constantly surrounding us and how the memory of our society is influenced by it.

Simon, you will be represented in twelve exhibitions during 2023. How does that feel for a young artist?

I have always imagined it somehow differently. In the past, I have often told myself: “I would love to arrive at the same stage this artist has”. For example, when I went to an award ceremony, I was convinced that these award winners could certainly no longer have any worries. And then, two years later, I won the same prize and yet I was even more concerned about the future than ever before! And I thought: “That’s not possible.” Even today, I am not yet where I want to be, and I always strive to develop my work further.

You started with photography, series like How far is a lightyear from 2018 made you well-known. If your goal is to develop yourself further, does this mean you are turning into a different kind of photographer?

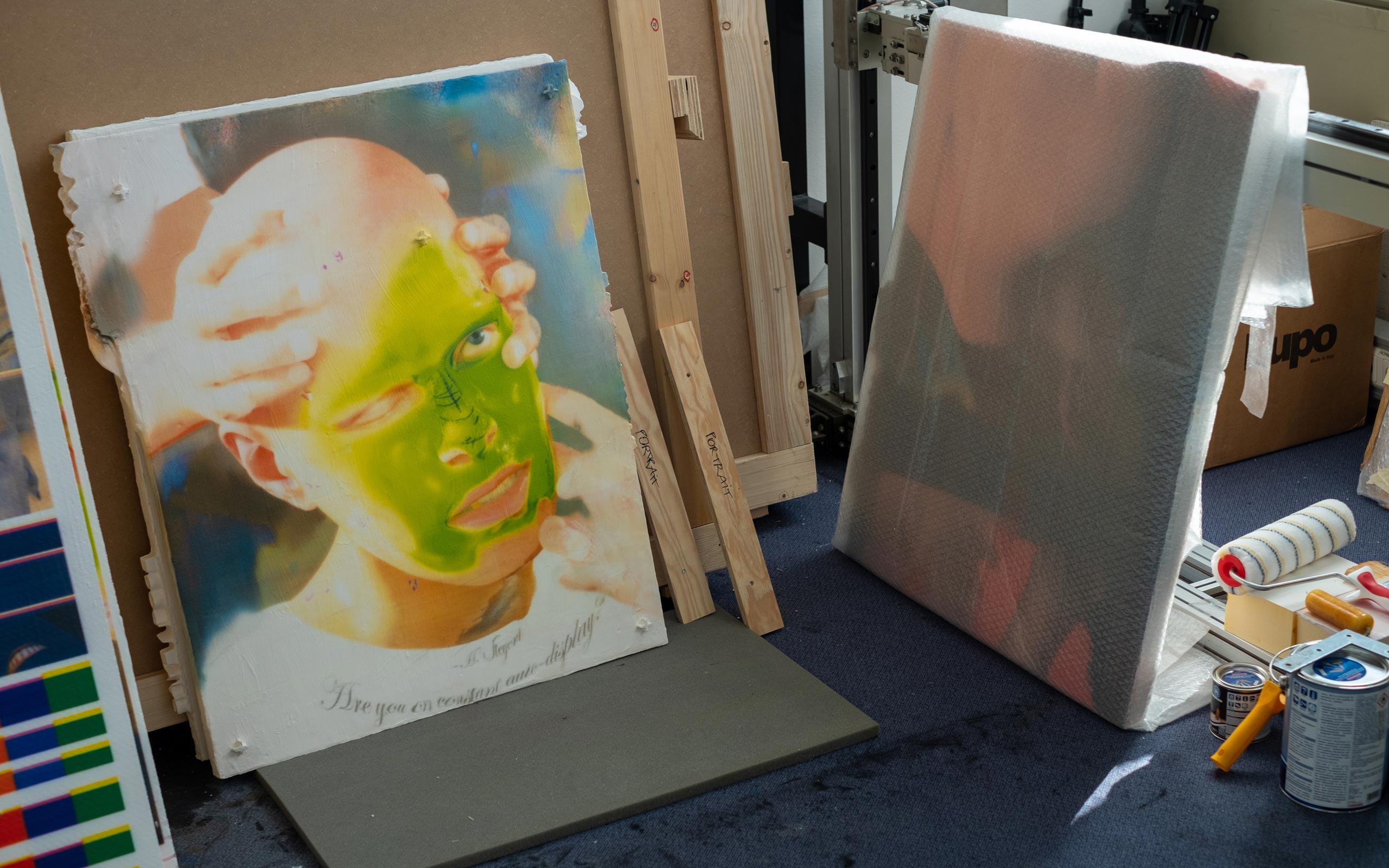

I wouldn’t call myself a photographer at all anymore, even though my new group of work is still essentially related to photography, because it is my source material. So, while the figures in my works are created from archived photographs, they are being assembled in the computer: the entire image composition happens digitally. That is why I don’t think the term photographer applies to me anymore, because I don’t look through a camera lens.

How did this move away from the camera happen?

At some point, the medium of photography was just dead to me. I see many problems with the way we, as a society, deal with this flood of images. I wonder if photography has actually done more good or bad to humanity. Because even if this medium can serve as a useful storage tool, it manipulates us heavily at the same time.

Nevertheless, you still work with archived photos. Is it because you are interested in the truth that a photo can (also) represent, or is it rather about the memory that the photo can provide for us?

Both, actually. Truth is, of course, an issue in photography. Even more so because we know now, unlike previous generations, that photos can be deceptive. I think it is exciting to understand how we cognitively process images: This process works in a similar way to the mechanism of the algorithms that our society has constructed.

Does this mean you are questioning the truth through your partly computer-generated images?

Yes! I think that photography will be obsolete in five to ten years. Of course, the intimate moment will continue to exist. But otherwise, everything we need will be available from photo archives. There is already a huge data pool of images! Companies will no longer hire photographers but will use computer programs to generate images for advertising, such as sunsets.

You criticize this development, but you use it nonetheless, don’t you?

That is true of course! I have a huge set of photographs taken by members of my family and myself, and with these I build new images, characters, and environments. With the help of the computer, I can control every finger, every head tilt, every eyelash in a picture. I use this process to reflect upon how we will deal with images in the future, how photography as such will develop in the future.

How has your work taken this direction?

It started slowly. First there were the computer-generated images, and then came the idea of moving from flat photography into space.

It almost sounds as if sculpture might appeal to you…

I always wanted to be a sculptor or painter. Ten years ago, I was already wondering how I could build a bridge from photography to painting, one that I am now slowly setting a foot on.

So why didn't you study painting in the first place?

Painting was actually the first thing I was really interested in. But photography was my tool, through which I gathered more understanding of image composition, and it was easier for me to handle. However, now my working process definitely has painterly elements, because even though it takes place in digital space, my approach using primer and layering is similar to painting.

Is this like a new medium that you are inventing?

Yes, absolutely! I don’t know anyone who works in quite in the same way. Of course, there are artists who work with robots, that’s nothing new. But that an artist works with archived photos, through which he generates 3D characters in new constellations, which in turn are painted by robots…

That sounds quite technical!

And it is! Each software has its own memory. I feed the robot with an image I have prepared on the computer, and the robot changes it slightly, then I add something to it, then it’s the robots turn again… It is a back and forth between the robot and me, and consequently between the memory of the robot and mine. I work with almost 25 kinds of different softwares, all of which are connected. It resembles the way we humans process images in memory.

How would you classify this new work?

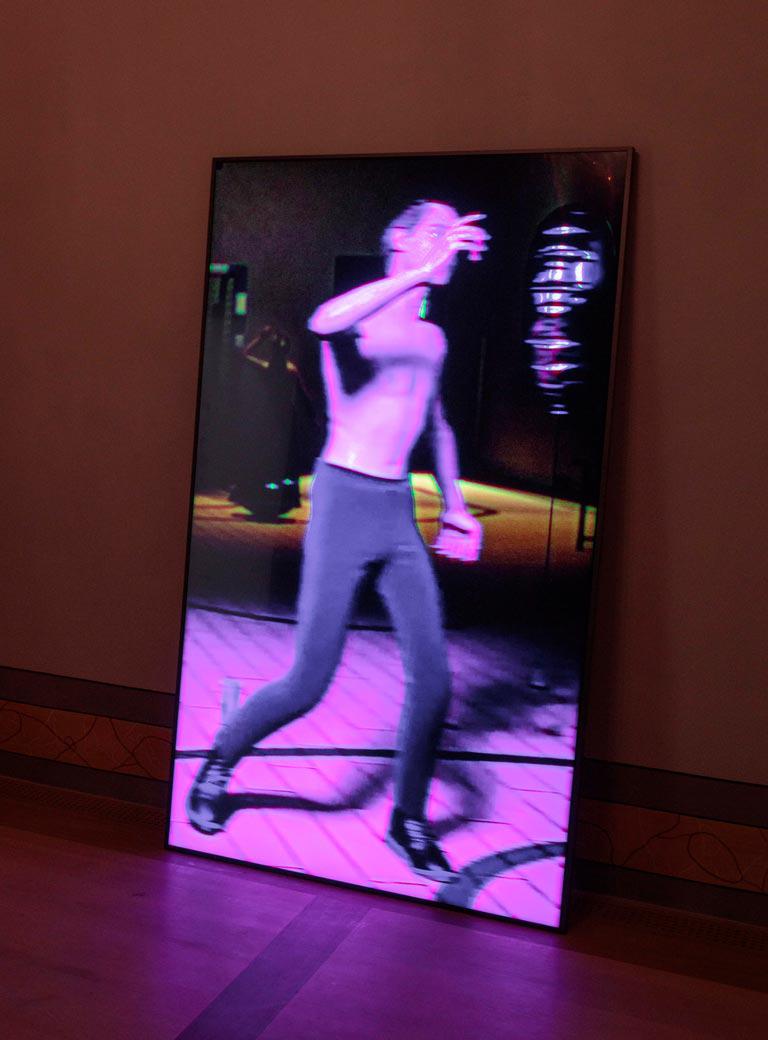

In any case, it is hybrid – and I don't really want to categorize it. Because these works are not proper paintings, nor photos, nor sculptures, even though they still exhibit painterly and sculptural elements. It is therefore difficult to classify them. In any case, for me, these new works have replaced my photographic works, and together with the video works and the installations they form the three cornerstones of my practice.

Which is your favorite medium?

The one I’m working on right now: leading from the photo to the painting process! However, I also like to work on my sculptures.

Is sculpture a rather new practice for you?

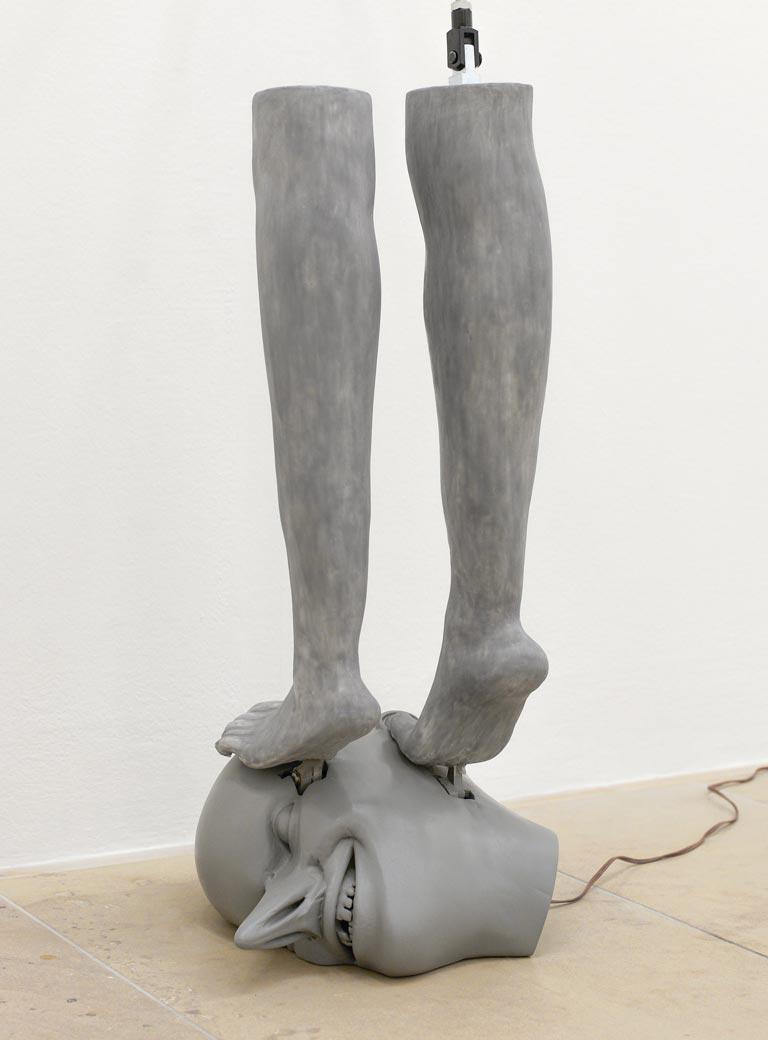

Yes, this is the first time I’ve done sculptural or installational work. At my first institutional solo show in Erlangen in 2023, for example, I showed an “animatronic” figure that stands on its tiptoes on a head and bobs up and down on it non-stop. The head of this large figure has a long nose, which scratches up and down a wall continuously because of the movement of the figure. For as long as the exhibition will last, the nose will scratch along the wall.

This movement sounds pretty hair-raising – and when you look at it, the sculpture probably gives you the shivers, doesn't it?

Yes, and it should! I’m interested in the somatosensory: how images can control us via our sensory organs. If, for example, in a hardware store advertisement we see someone running their hand over a wooden slat, we feel it as if we were performing the movement ourselves – and we are thus deliberately manipulated. That is what I try to incorporate into my work.

Is this a new path from you?

No, I was interested in exploring the somatosensory principle from an early age. For example, I showed it in my group of works How far is a lightyear? through the photo of the boy with ants on his back – you can almost feel them crawling over his skin.

In contrast to this photo, however, your work today is further removed from your personal experience, isn’t it?

Yes. Now I am scratching on the surface of images; I concern myself with image manipulation and the dismantling of facades.

Your early work hinted at strong autobiographical issues. The genre of autofiction is also in great demand in literature; do you see yourself in this tradition?

Good question. I always start from my own experiences when I address topics such as trauma. This means I start from the personal – how I deal with memories – and then turn it into the collective, how we all deal with memories. In other words, my themes are personal identity and collective identity, and how we form them. Because we are so strongly influenced by the images that surround us. I think we have built up a collective data trauma.

Can you explain?

It is exciting and frightening at the same time: Image technology has built up systematics and principles that are comparable to how trauma that we experienced deals with the related images in our heads. Social media, for example, has algorithms that work in a similar way to how we humans process images in our memory. And the interesting thing is that we took this system – which is actually a weak point in our cognitive process – as a template for the algorithms. By the way, there are also scientific studies on the interaction between psychology and technology.

This brings us back to memory and trauma, issues that also stem from your personal experience. How do you remember your childhood?

To put it mildly, the family dynamic was difficult – and I am very much aware that I am not the only one with these kinds of experiences. My themes of identity and toxic masculinity probably originate from there, but I don’t want to dwell on it.

You grew up in Wels in Upper Austria, got into photography at an early age…

I started photography when I was 14, thanks to a teacher who was my first supporter. At that time, I had a naïve approach to photography; I thought it was just about photographing flowers and things like that. But the teacher showed me what photography could do, and after three minutes I knew: This is my tool!

Later you studied photography at the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna…

I attended the photography and time-based media class. I felt like an outsider, because the class had a focus on magazine photography, which I thought of as a classic service provider. I didn’t like it much... And then came this crucial moment when I was standing in the kitchen with my professor, and she suddenly asked me: “You don’t really want to do work for magazines, do you?” and I couldn’t help but answer “No!” from the bottom of my heart (laughs).

Nevertheless, you had your first international success in 2018 with photos for American Vogue, of all things…

Yes! Three weeks after that kitchen conversation, Anna Wintour from Vogue suddenly wrote to me, asking if I could do an assignment for her. I had had an exhibition in New York at the time, she had bought two works there and consequently contacted me.

Isn’t such an assignment for Vogue fantastic?

Well, as far as fashion or commissioned photography is concerned, of course! It’s Mount Olympus! So I said “yes”, and that was my first assignment – fashion after all. Of course, that was absurd, since I had said before that fashion was not my thing.

What did Anna Wintour buy at your exhibition?

Two photographs from the work group How far is a lightyear. One was the boy with ants on his back, and the other a 3D generated sunset. The whole sales experience was so weird because the very excited gallery owner in New York told me: “Guess what just happened! Anna just bought two pieces!” and I replied, very clueless: “Who is Anna?” and she almost screamed: “Anna Wintour!” (laughs). But I also have to say that I have moved on artistically since then.

Who are the artists who inspire you?

In recent years, I have been extremely interested in Bruce Nauman; I just hadn’t understood his work properly before! Now I feel something in it... and Sterling Ruby does epoxy resin work that was also a catalyst for me. In general, we artists always remix, there is no longer anything genuinely new, and there probably won't be either.

To put it bluntly: Is it still possible to make art after Duchamp?

(Laughs) Who knows! We artists take something and hope that something new will come out of it. That’s the way it is!

You’ve already had very prominent commissions, such as portraying Balenciaga’s designer, Demna…

Yes, that was a commission from Zeit Magazine. So I went to New York to attend the Balenciaga fashion show, got to know some “celebrities”... But honestly, that’s not my thing, and I was a bit overwhelmed. I have to put that at the back of my mind; it distracted me more than it did me any good. It’s just not my way.

What do you do to wind down?

Work! I currently work 17-18 hours a day and sleep little because of the production for the new exhibitions. I’m happy, of course, but it’s stressful! I don’t even know how I’m going to manage it all (laughs). Besides, I can’t say no, I’m just not used to it yet. In the past, I always said yes, because as an artist you are happy about the interest. But now I have Sophie, my studio manager, who says no for me – because I would still say yes to anything.

Is now the moment in which you think you've made it as an artist?

I don’t think that moment will ever come. Or maybe it is coming in the future, at least I hope so! There may have been a hint of it when I signed with Galerie KOW. I’ve been wanting to work with them for five years, then it finally happened! They took my work to Art Basel, it was all incredible...

Is there a risk of becoming big-headed?

Actually, no. For me, it’s not about what my lifestyle looks like, but about my work and the values behind it. The most important thing is work.

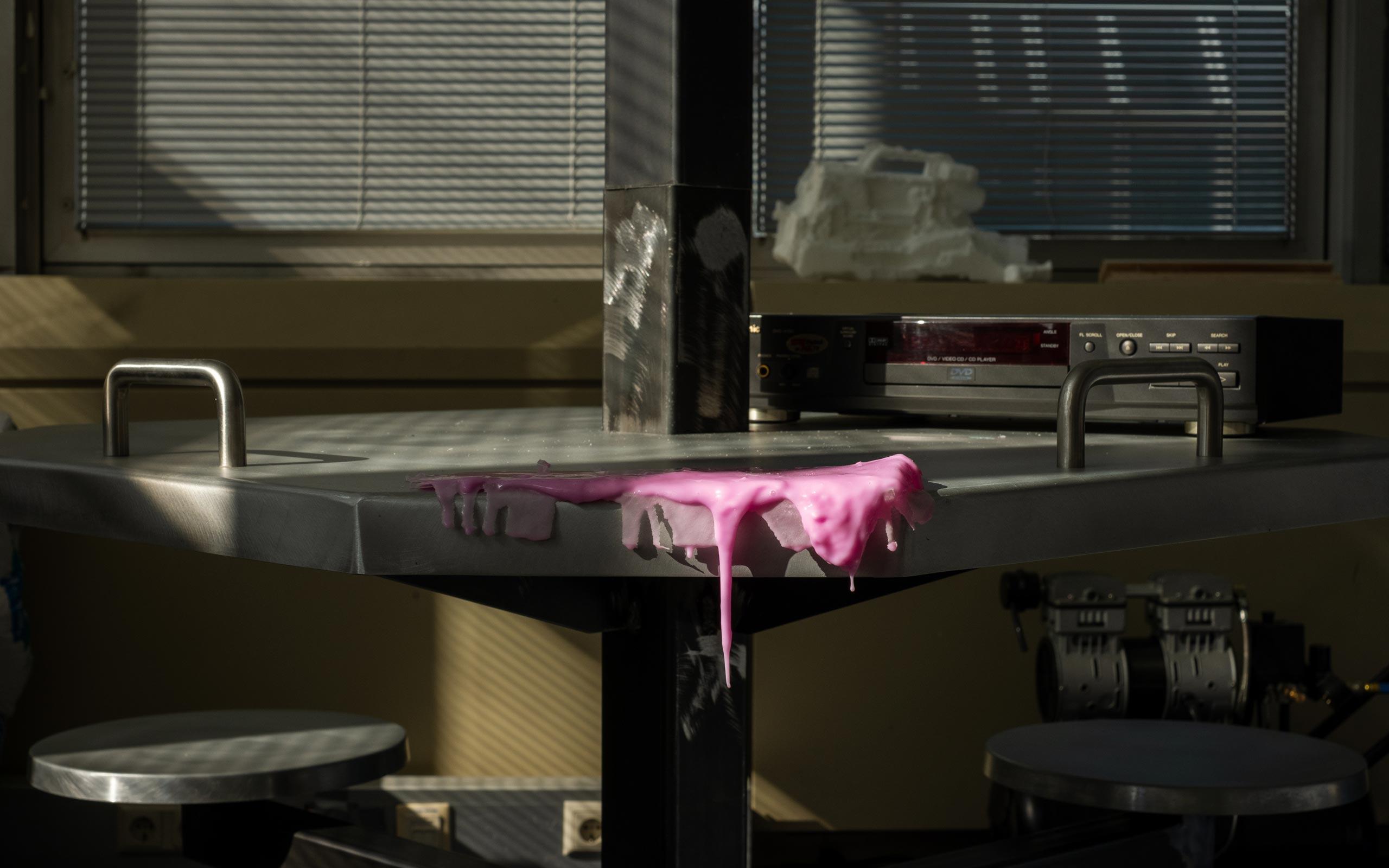

Echo figure (Gray matter cycle), 2023, Courtesy of the Artist and KOW - Berlin, @Simon Lehner

Installation shot, Kunstpalais Erlangen, solo show I love you like an image, Kunstpalais Erlangen, @Ludger Paffrath

Installation shot, Kunstpalais Erlangen, solo show I love you like an image, Kunstpalais Erlangen, @Ludger Paffrath

Echo figure (Gray matter cycle), 2023, Courtesy of the Artist and KOW - Berlin, @Simon Lehner

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov