The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

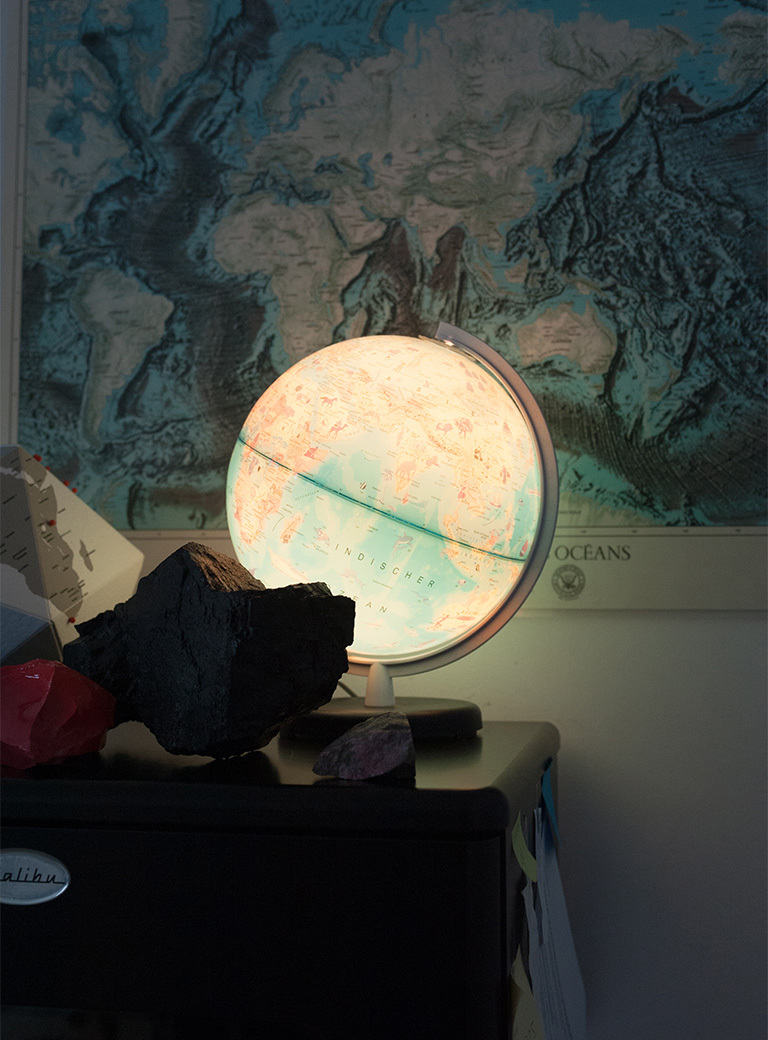

Sissel Tolaas is a smell researcher and artist. Since 1990 she has been collecting and investigating smells from all over the world. Her background is in organic chemistry, linguistics and visual art and her research and projects have been honored by numerous international scholarships and awards and her olfactory projects have been experienced in museums throughout the world including MoMA, the Centre Pompidou, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. In her Berlin laboratory we talked with her about the importance of smell in our lives and her huge smell archives.

Sissel, were you aware even as a child, that smells would become “your” life subject?

I think I can say I have used all my senses intensively from a very young age. I grew up in Scandinavia and was always a very curious and hyperactive child. I did a lot of outdoor activities. For my interest in “life”, in its absolute meaning, it was important to grow up outside of the big cities, maybe I developed a greater olfactory sensitivity because of that. From very early on I was interested in ”air”, the air that surrounded me, and the matter of breathing. What does it mean to be alive? Does the air that I breathe contain information that could be important for keeping me alive? And, in general I was very interested in everything invisible.

How exactly did you explore your senses?

Through literally growing up outdoors. I’m convinced that made me very alert in all my senses. In Scandinavia, a lot revolves around the weather: leisure, pleasure, business, mood, and so on. Once I even created a slogan, installed as a light object, titled It must be the weather. This subject has accompanied me throughout my entire life. The meaning of the slogan is that one can actually blame the weather for everything.

Think for a moment how people talk about the weather. It is mostly by using the terms: good or bad weather, in spite of its tremendous importance and the fact that there are so many variants of “weather”. I was wondering why there was this lack of a differentiated language when talking about weather. To explore this further I decided to study organic chemistry and linguistics.

Through chemistry I did various experiments around extreme weathers conditions with the purpose of discovering how people would speak about it. It might sound a little odd, but I found that the people who took part in my experiments later spoke differently about the weather. To make a long story short, from that point chemistry and linguistics became the focus of my attention and hence, I arrived at “smell”.

What is it that fascinates you about smell?

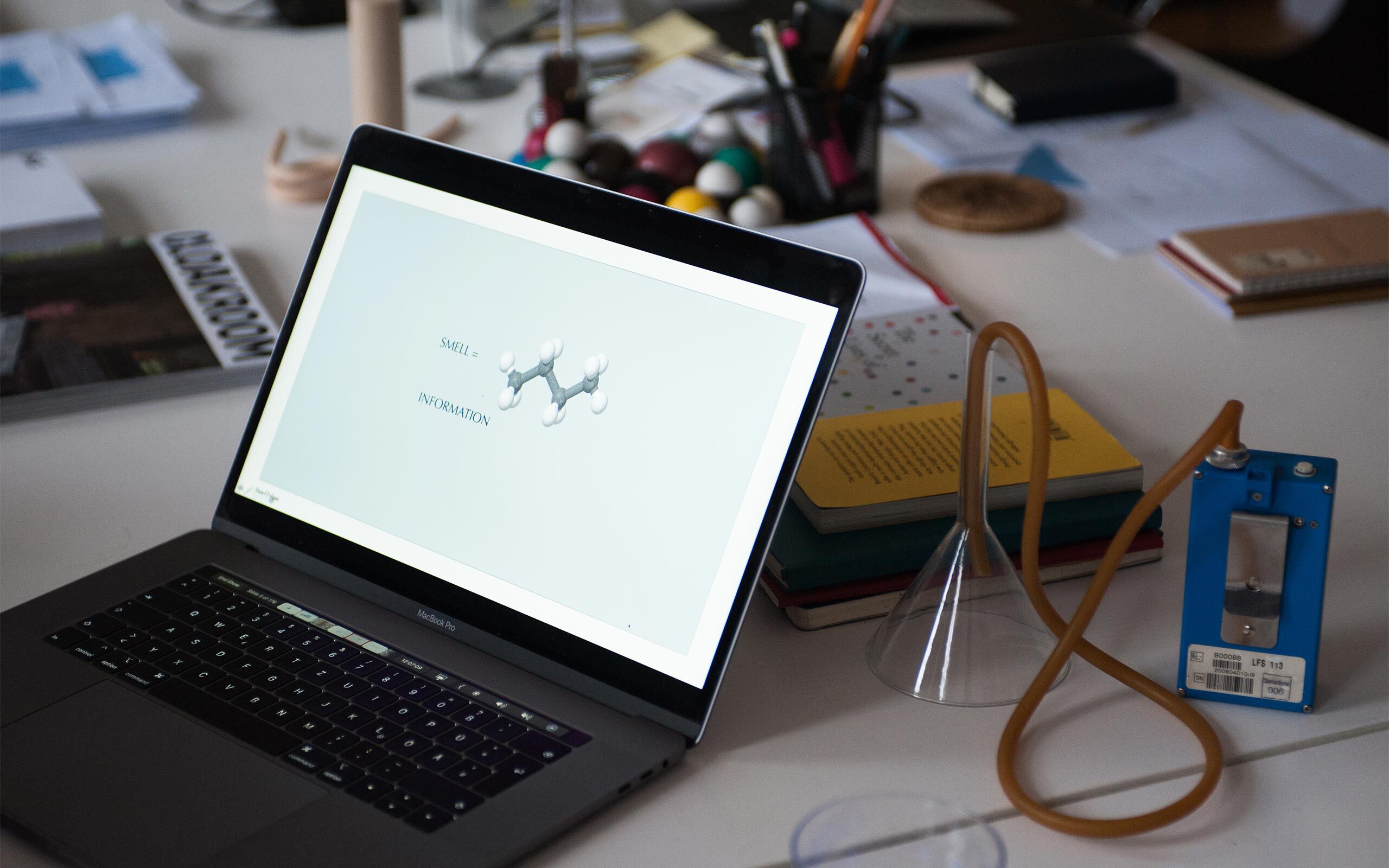

Everything. In the beginning was actually not the word, but the smell. Chemical detection was the communication tool used by the first bacteria appearing on earth, for food and reproduction. Smells are used constantly, consciously or subconsciously, to communicate among insects, plants, animals, and human beings. The nose is the most efficient human interface to inform us of our surrounding reality. Smell molecules provide the purest and most efficient information. In general, most people don’t know what smell is and, even worse, do not know what it means to smell something.

We take up to 24,000 breaths a day and move up to 12.7 cubic meters air with our breathing. With every breath we take, we inhale thousands of smell-molecules. They all provide sophisticated information about that very moment. Smells trigger memory and emotion quicker than any other sense. Challenging people to use their sense of smell gives them new methods and means to understand the world. There is a playful aspect about discovering the world through smells. Learning in the context of emotion is essential to learning.

How would you yourself describe your artistic approach?

My method of working is scientific, and I regard science as a cultural product. My solutions, results and products are creative. Around 50% of my projects and experiments are displayed in different creative contexts. In the creative world you are allowed to be subjective and this freedom is very important for the questions I am asking. I get an immediate reaction from a diversity of people. In the science world you can ask the same questions, but you have to remain objective (we) and express yourself with dry academic papers and you maybe get a response months or years later from a small group of academics before being able to move on to the next step. Also, since “smell” is about life and being alive, I need to be where life is happening. Being in the field – and showing up – is half my job.

Who has supported you and your ideas?

I was always a loner. I think I can say that I was borne emancipated and independent. From 1990 till 1997, I was my own guinea pig and decided to travel the world to challenge my own smelling skills and to try to understand what smell is. I was curious to find out the state of “smell” in other cultures and the various topics I explored were among others: politics of smell; tolerance and smell; climate and smell; language and smell. After seven years in the field I was prepared to devote myself to “smell” for the rest of my life. Not only had I become an advanced “smeller” but I had restored passion and commitment to my life.

In 1997 I decided to make Berlin my hub. Up until this point I had been relying on scholarships, generous grants and support from various countries and institutions. In 2003 I merged the private with the professional and moved my studio home. By then I had already worked with various companies who let me use their (smell) chemistry labs. But I was still struggling to survive. Furthermore, the topic of “smell” was alien to most people, so it was very tough. But in 2002 everything changed. I met with IFF (International Flavors & Fragrances Inc.) and it changed my life. They offered me 100% support. I immediately set up a professional smell chemistry lab in my studio – 2004 Smell Re_searchLab Berlin was borne. I am so grateful to IFF. Without them I would not be where I am today.

How do you collect the smells that interest you?

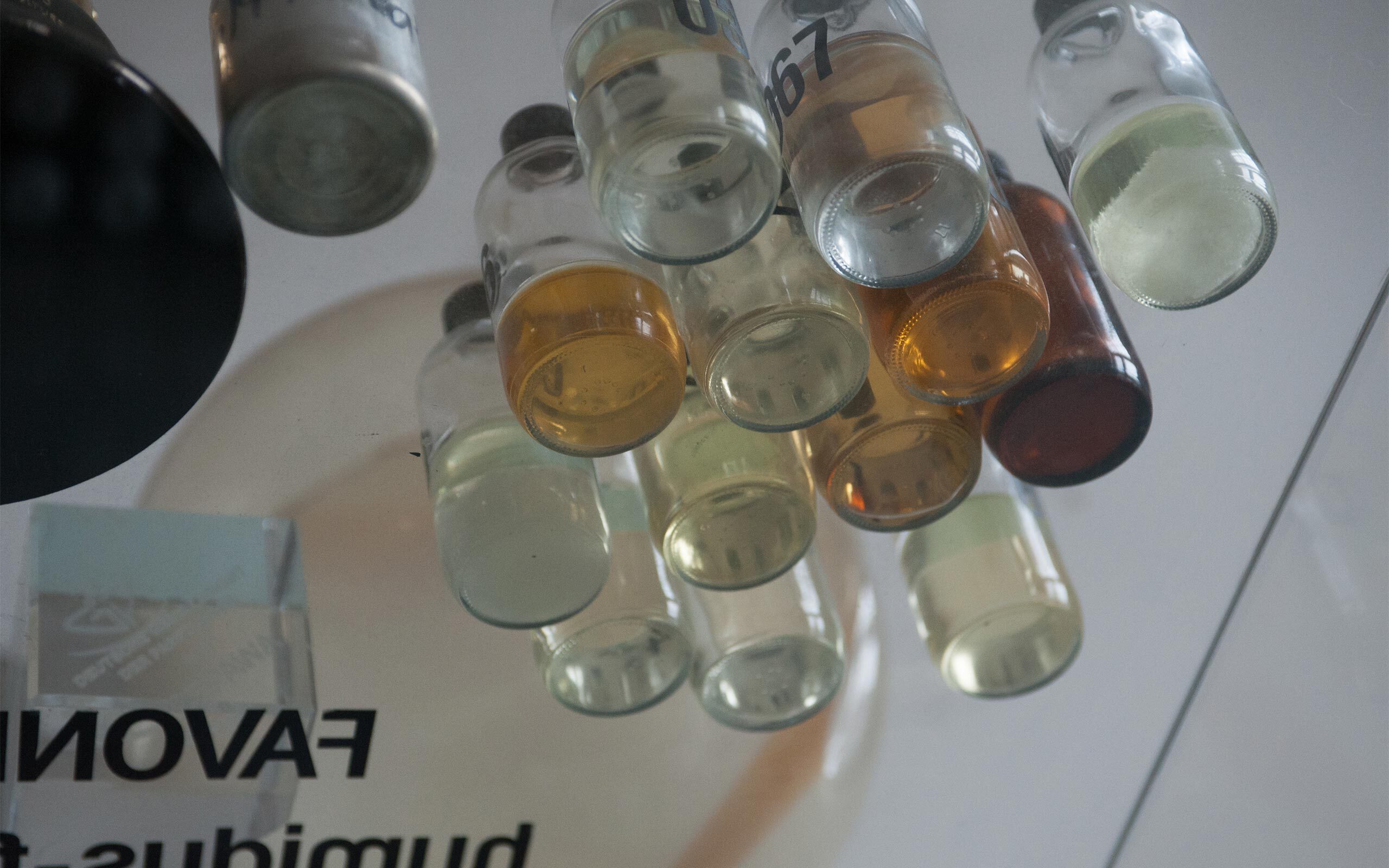

As I have said, being in the field is half my job. Depending on the topics of concern I explore the context with my own nose first, then I decide whether to advance with smell-recording technology or not. At the very beginning – my first archive – I collected samples of the actual smell sources and placed them in metal boxes. The boxes were vacuum-sealed so that the sample and its smell would be preserved for an extended period. Each box was labeled and marked with the relevant information regarding geographical location, context, topic, date and time, and language. The archive consists of 6,730 samples. Later, I obtained access to various recording technologies, which meant I could actually replicate the smells that concerned me and to forego the necessity to collect and bring the physical smell source samples to the lab. I have been collecting and recording smells since 1990 and the results are archived under various categories including: language, physical smell sources, complex smell structures, individual molecules, replicated smells, etc. I don’t know the precise number I have collected, but the figure is in the thousands, approximately, 15,000.

How has the collecting of smells changed with the development of technology in recent years?

With the support of IFF Inc. I now have access to a lot of science and also technology in the field of smell. I am currently using mobile devices that enable me to be flexible and collect and sample smell molecules emitted directly from smell sources. Through chemical analysis lab chemists break down the collected samples to individual identifiable molecules. Using this data, I can chemically reproduce the recorded smells – as close to the original as possible – in unlimited quantities for various purposes.

One technology I am using is a Headspace app. It enables me to literally take a snapshot of a nanosecond of the movement of a smell molecule. Originally this technology was used in greenhouses to record the blossoming of flowers for the purpose of copying their molecular structure. Smell molecules need air to move so these technologies operate like efficient air vacuum cleaners.

Each of my smell sampling and recording devices have a molecule data base which in turn adds new samples to the existing archives. The different categories within the archives include: City SmellScape, Body SmellScape, Ocean SmellScape, Nature SmellScape, and Space SmellScape. With other advanced technologies I am then able to break down the various smell recordings into sub-categories – totally based upon the various indications that the individual molecules give.

You just mentioned City SmellScape, as an on-going project of yours, in which you have collected up to the present time, the smell of 52 cities. What exactly does this project look like?

Each of the City SmellScapes has a different focus depending on the client and the topics of concern. Topics can vary to include everything from pollution and navigation to the topic of segregation.The method of working and approaching the topics is always the same. Doing the fieldwork myself is essential and also including the locals in the process is absolutely important.

A concrete example is SmellScape Melbourne Past_Present_Past – a very site-specific project about history, archaeology, the legacy of the land, its people, and the topic of memory. I investigated into the specific location of the NGV (the National Gallery of Victoria) in Melbourne, for the first Triennale in 2017/2018. Segments of the earth and land were analyzed for traces of smells – from tens of thousands of years ago up to the present – and I was working with local indigenous experts and academics who played a crucial part in deciding on which smells could represent what. The selected smells and smell indications were then placed on abstract artifacts – only the embedded smells told the content of concern. So the surface of these objects became the skin of the earth – and only by conscious activation through touching and then smelling one could activate the smells. I call these objects Emotional Artifacts.

These smell codes and smell references activated past memories and generated new ones related to the site’s past and present. It was a project about the loss of constituted memory and the sense of smell as the generator to regain it. The focus was also on the human body and how it can interact with history in a new more holistic way by adding smell, and the emotions triggered with it, to the narrative – an unforgettable experience. These projects then become archives that are given back to the relevant communities.

Once you appeared at the Berlin Konzerthaus on the Gendarmenmarkt wearing a very disturbing smell that caused irritation among some people. Do you use your creations often as perfumes?

Smell, and in particular its chemical compounds are used by all species to send messages. Most animals do this consciously, humans unconsciously. I use smells to say something I otherwise would not say directly, these can be in the form of: stay away smells, listen to me smells, and come to me smells; I use smells only for such purposes, and it is very interesting to observe people’s reactions, that is half of the enjoyment. People are very confused if one smells in contrast to one’s appearance! In a world dominated by the visual, people are hardly able to process the ability to receive other forms of information.

In 2003-2004 I started a research project at MIT called The Fear of Smell, The Smell of Fear. The project is a study on smell and identity, smell and tolerance, and smell and psychology. Can one smell that a person is afraid? Can a smell make a person afraid? I collected and recorded body sweat of phobic men in the moment of fear attacks. The replicated smells were placed on walls with a nanotechnology that enabled the smells to be locked into the wall. The wall became a metaphor of the human skin, and only by touching the walls – as if you were touch bodies – one could activate the smells. The project is still going on and has been traveling all over the world and the reactions are beyond words.

Can you specifically trigger feelings in people with smells?

Emotions are complex systems. Smells in general trigger emotions. In all my projects Emotional Intelligence is essential. Certain projects are meant to evoke very specific emotions more than others. One project of that kind was a recent project I did for the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall Hyundai Commission 2018, with Tania Bruguera. I developed a smell that made people cry on the spot. People were lining up to cry. This was a very impressive experience.

With the multiple alternative realities and intelligences such as VR and AI we should not forget that humans are equipped with the most sophisticated software and interfaces on our own bodies: the senses. These are free of charge and smarter than any digital sensors will ever be. What makes us human and different from any machine is that we have emotions. I think there’s a long way to go before robots will be able to feel or show emotions.

In general, most of my projects deal with undertaking a “sensory re-boot”, an invitation to get out of one’s comfort zone and challenge one’s perceptions. The result can be more sensitivity and empathy, bringing improved performance, wellbeing and happiness. I believe in a world with significantly greater global instability, it is important that we carefully consider and rethink our conventional modes of communication and our decision-making biases.

Is there something that you yourself like or dislike in a smell?

In my world there are just “smells”. We are a born neutral! There are no genes that tell us what is bad or good. The sense of smell is there to find partners and to find food, independent of context and where on the planet you are. Education and cultural heritage determine one’s relation towards smells. We live in a part of the world where we deodorize and sanitize to such an extent that it’s not better for the body, for the planet and beyond.

Are there any prejudices about your work that you occasionally have to deal with?

In general, most people are prejudiced towards most smells. Since most of my works are very immaterial it can be difficult for many people to relate to them. As we are so used to rely on what we see, also in the context of art, very often my work is ‘overlooked.’ But I actually take that as a compliment. I have been around for a while and I have never been so busy, so I guess people’s prejudices have also improved at the same time.

I even have commercial clients that want to apply some of my research and even my most hardcore smells for various purposes, so I guess the world is changing for a fact. Tolerance is a keyword to peace. And tolerance starts with a smell. I hope I have contributed to a better understanding of smell and also caused a bigger acceptance of certain smells. Even more interesting is that most of my smells are existing: Smells taken from Real Realities so if anyone has issues most likely those issues are issues beyond the smells. The smells here function just as triggers to bigger issues.

How does the art you create fit into our times or even the future?

I am not interested in fitting in anywhere, neither in terms of time nor category. My passion for life is what drives my work and life is independent of trends. The senses will always be there as long as there are species around. I am working on a project where non-humans will be my target, so I hope with that I will make my work everlasting. There is no limit where I can put myself, so I do not see any danger of not being busy. I can smell tomorrow but I do not know about it yet.

Interview: Dr. Sylvia Metz

Photos: Kristin Loschert