Sonia Leimer’s art is space occupying – not because her works are especially large or intrusive, but rather because the artist has developed a finely tuned sense for the understanding of occupied space and the in-between space that surrounds us. Her works in the public space as well as her installations and sculptures refer to aspects of the environment that would be unseen otherwise. In the interview, the artist who lives and works in Vienna, speaks with us about architectural tools, her fascination with industrial materials, and how her art can become a refuge for students.

Sonia, your studio is a really interesting space in the basement of a l950s apartment block. Although night is beginning to fall, it is still very bright in here.

In the Second World War, the Gründerzeit style buildings were destroyed. In 1958, these rows of large buildings were constructed following a completely different concept of free space than that of housing from the period of early industrialization. The studio opens out to green areas on all four sides, very different than the dark studios I had before. I love this space because I am a fan of Carl Auböck, who designed the building. Auböck had a strong design aspect in his work and in that sense was not a classical architect. He worked a lot with the interior space and furniture, and in this pursuit tried to think several orders of magnitude simultaneously. How can the position of the cloakroom be as important as the position of the building in an urban setting?

The intense involvement with space plays an important role in your work as well. What does it mean to you?

I didn’t study art but architecture, and have therefore dealt predominantly with theories and concepts of space. One of the teachers who was most important to me, Joost Meuwissen, had a very artistic approach and as a result I began to approach the designing of a space with quite different questions. This open approach, that spatial concepts can’t be understood only in the context of a built structure, had already interested me during my studies and after graduation I decided not to work as an architect but as an artist so that I could handle space more freely. If I had stayed in architecture I would have dealt with architectural theory, but ultimately artistic work and experimentation with materials were more important to me.

Was the question of micro and macrostructures, that is, Auböck’s cloakroom and housing block a reason for you to turn to art?

The question of scale is certainly different in sculpture than it is in architecture. I was particularly attracted to the greater scope of possibilities in the arts. In architecture you have to work more with specific requirements. Even if you are fortunate to be a successful architect, you are limited in the spatial translation of ideas. Nevertheless I am glad that I studied architecture and not art, even if the transition was difficult. Now I can apply my knowledge of spatial aspects from architecture in a different context.

Which aspects of architecture are so interesting to you that you integrate them into your artistic work?

I have always been interested in the architecture of the street: the facades, the corners, asphalt. In architecture these details often are not really appreciated. The street serves simply serves the purpose of getting from A to B. At the same time, however, the street is the architecture that connects all the buildings of a city. It is the place were the interactions between people who don’t even know each other take place; it provides an opportunity to design public space.

In this respect one could understand the street as the in-between space or placeholder? It is interesting that you made a series of works with the title Placeholder. What is the missing element for which the place is held?

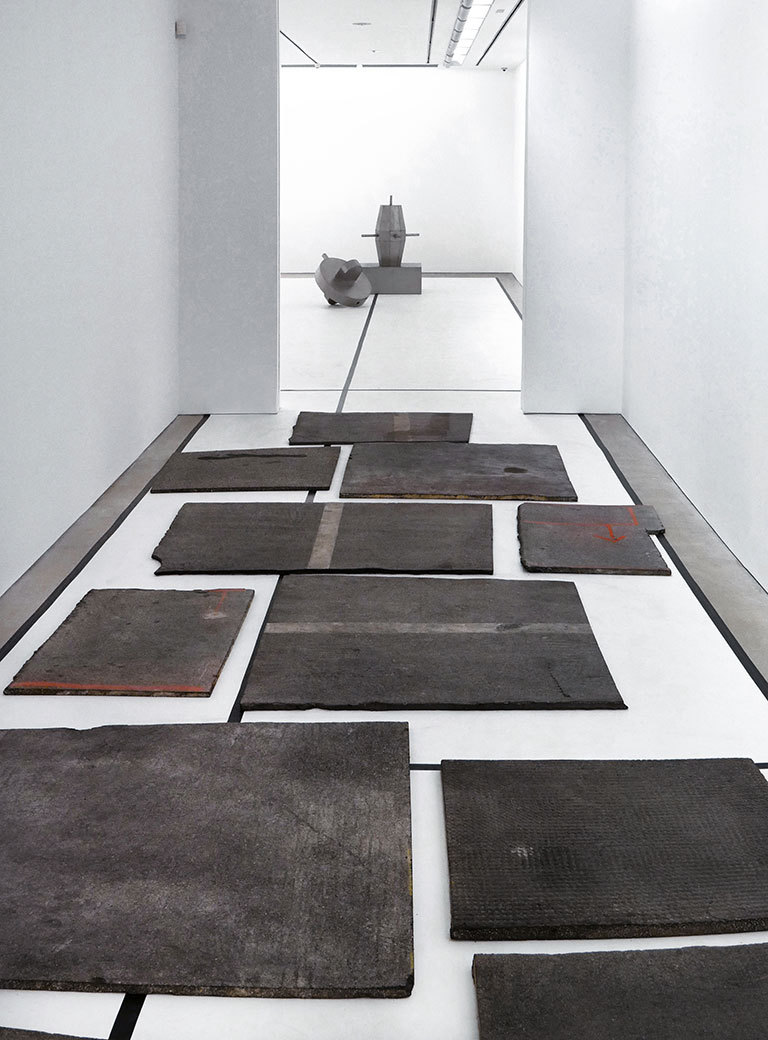

The concept of Placeholder is about our acting in space. Objects that I observed during a residency in Istanbul have inspired this work. I could observe how someone tied a piece of concrete with a lock to the street in order to hold a place. Through the connection of the object with the asphalt this person has clearly defined his space although the street doesn’t belong to him. I found the idea to take possession of a space with an object interesting, and a series of sculptures developed from pieces of asphalt, which I combined with other materials from the street like handrails or reinforcement bars. These Placeholders speak exclusively about action and against form although they are certainly a formal expression. They are ambivalent and I like that.

“Placeholder” sounds almost immaterial although your work is always very substantial. You are using materials like I-beams, concrete, and bricks. What is your approach to these materials?

Materials derived from architecture inspire me and I find it exciting to use them in a very different scale. Often, the materials are in a very raw condition like the uncut I-beam, raw bricks, and unrolled cigarette papers. These forms often appear strange to us, because they originate from a production process that we don’t know.

Does that mean that you visit factories in order to gather material for your projects?

Part of my work process involves expanding my studio in that way. I find it very interesting to see where the material with which I work comes from. I also love to work with handmade high-tech materials of the type used in the aerospace industry. For example, I made silkscreen prints on PVC foil that had been coated in vaporized aluminum. At the time, it was the thinnest and lightest material in existence. I found in the factory a roll labeled “failure”, an experiment for which no use had been found because the material was too fragile to be used in the robust environment of the atmosphere or outer space. I printed the first satellite picture of the earth on it, which was also a “failure” because it could not be recognized. Is it a reflection of the sun in the Pacific Ocean, simply a cloud, or the result of a technical error? The NASA report states philosophically: “A row of dots form a line and eventually the line forms an image”.

Another material you used are paper rolls the profile of which you print. What is that about?

The great thing with a huge roll is that it can expand. It can be a firm, sculptural body but at the same time something flat. On the first roll that I printed is a view of Chinatown in New York, where I bought the paper. The work is entitled Orchard Street and the idea was to make a portrait of this street. Earlier, the area was known as “Little Germany” because many German-speaking migrants had settled there. In the meantime, the district is known as “Chinatown”, but now there is an extreme pressure on the area because real estate prices are skyrocketing. The quarter is transforming permanently.

In your work, you are constantly examining socio-cultural aspects like this, which is also the case in your investigation of the significance of apple cultivation in your home region of the South Tyrol.

Through Joost Meuwissen I learned to see urban space as not distinct from rural space. The rural landscape has been shaped by agriculture just as the cityscape is a built up and modeled space. In the case of the Southern Tyrol, I studied measuring tools designed to grade apple size in order to demonstrate how such a tool facilitates a worldwide categorization of our food. The work certainly has a personal aspect inasmuch as I know of the measuring tools from my childhood and have worked with them personally. I found it interesting to scale them up to the size of the human body, thereby completely changing their perspective.

Many of your works, for example the Placeholder sculptures or the I-beam Stool carry a certain functionality within them. You have no concern about approximating your art to everyday objects?

Not at all! I like to see my works as a pedestal which experiences an expansion through the viewer and are used, at least in the imagination. A pedestal also has a placeholder function. It is there and has a strong formal component, at the same time it is something that one actually blanks out as simply a carrier for something else. The same holds true for the I-beam, because it is a placeholder for someone who wishes to sit on it.

What apart from its use stands behind the cushioned I-beams?

The work has a very strong component that refers to the city of Iwanowo and deals with the declining textile industry there. I found old fabrics bearing propaganda messages that had been produced there in the 1920s and 1930s and had found their way as cheap goods into many Soviet households. The avant-garde design was a means to disseminate messages regarding politics, progress, the military, electricity, and space travel into everyday lives. I have reproduced some of these historical designs myself using a heavy material from the construction industry to cushion I-beams. This seemed to me an exciting combination by which material of our built environment is combined with a form of pictorial ideological charge of this reality.

You create work for exhibitions in museums and galleries as well as for the public space. Does the way in which you work on projects in various contexts differ a great deal?

In the public space I have a very different approach than in a gallery. In the public space I show an interest in the spatial relationships and the history of the particular space. That way I can work with architectonic elements in order to enhance or change the spatial qualities. In Salzburg for example I have built a fragment of a building in an interior courtyard. In this case, in the course of renovation, the interior courtyard had been completely covered with glass so that schoolchildren could be constantly observed by teachers. I have picked up on this situation and built an architecture comprising of a façade and a staircase. The “White Cube” of an exhibition space allows me to think a bit more independent of the spatial contexts and I can transport things from the outside in, but I also try to integrate always specifically designed settings in gallery exhibitions.

Is there a fundamental message that you want people to remember who encounter your art in various contexts?

Principally it is about the experience of space, concretely in the public space and more abstractly, as installation, in the interior space. I hope that my works inspire people to look for the meaning between things. To this end, they often consist of fragments which cannot be seen when they are taken out of their context and placed in a different relationship to each other. What connects my works for the exterior and those created for the interior is the idea that I combine these aspects in a chronological sequence.

You have taught at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and the ETH Zurich. Are there things that are particularly important to you that you transmit to your students?

I have been impacted by people who question everything – even the professional profile. That is what continues to interest me and what I want to transfer. At the same time, the students ask many questions that I find exciting. It is important to me that I stay in a context in which knowledge is generated and in which much exchange takes place. That’s why I, too, learn something when I teach. In the meantime I consider teaching a firm part in my artistic practice.

Can you possibly name some people at the interface of architecture and art that have impacted you?

Alice Könitz and Christian Kosmas Mayer are two examples of artists from my surroundings with whom I frequently collaborate. Mike Kelley, Dan Graham, and Joëlle Tuerlinckx are representatives of an earlier generation who are important to me. I also like positions that negotiate space through film like that of Barbara Hammer with whom I have already collaborated.

Can you tell us the next projects that you will be working on? Are there new topics that you find exciting?

I have worked a lot recently, but right now I have time to experiment and to dedicate myself to larger projects. I am working predominantly on a series of new sculptures which I had begun in my studio at ISCP (International Studio and Curatorial Program), New York. During my stay there, I gathered many new impressions in the public space and I am in the process of transforming this material into a sculptural work. But before that I am completing an art-in-architecture project that continues the idea of the Placeholder, in cooperation with a large brick producer.

Exhibition view Avenir Next, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich, Photo: Wilfried Petzi

Exhibition view Avenir Next, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich, Photo: Wilfried Petzi

Exhibition view Avenir Next, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich, Photo: Wilfried Petzi

Sonia Leimer, Autoterritorium, Photo: Marina Faust

Sonia Leimer, Autoterritorium, Photo: Marina Faust

Sonia Leimer, Autoterritorium, Photo: Marina Faust

Interview: Gabriel Roland

Photos: Florian Langhammer

Links:

Sonia Leimer's Website

Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, Vienna

Barbara Gross Galerie, Munich