Viennese artist Sophie Hirsch explores the intersection between materiality, movement, and tension, where strength and vulnerability coexist. Drawing from her early experiences in a New York Pilates studio, her work examines the body’s physicality and the relationship between movement and structure. Using materials like silicone, metal, and other unconventional substances like Thera-Bands and fascia balls, she creates pieces that challenge perceptions of discomfort while offering moments of release and transformation.

When did you first know that you wanted to be an artist?

Around the age of 14 or 15—that’s when I began to actively look for influences and connections beyond my immediate environment. At that time, I was searching for an outlet, and I found that in the work of other artists and through music. Art and music became a refuge for my emotions and over time, my teenage angst grew into a more sincere, outward-looking way to process the world in a more thoughtful way.

Did your parents support your wish to be an artist?

Actually, yes. Like most 14 or 15 year-olds, I began experimenting with photography in the early days of digital cameras—long before iPhones. I didn’t have a tripod and couldn’t capture certain angles, so my mother ended up taking many of those photographs of me. Having her be a part of these first creative attempts was a sweet way for us to connect. She didn’t really understand what I was doing and was probably pretty unnerved by it all, but she supported me and never told me to stop doing it. Looking back that really means a lot to me.

So what were your first steps as an artist?

In terms of education, my first steps were studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for two years. After that, I moved back to Vienna and continued my studies at the University of Applied Arts. I initially focused on photography but soon realised that I was more interested in sculpture. I often found myself building things to photograph and, eventually, I understood that I could skip that step altogether and just focus on constructing environments. That moment was the beginning of my focus on sculpture.

Could you share an anecdote or a turning point in your career when you realised the direction your artistic practice was taking?

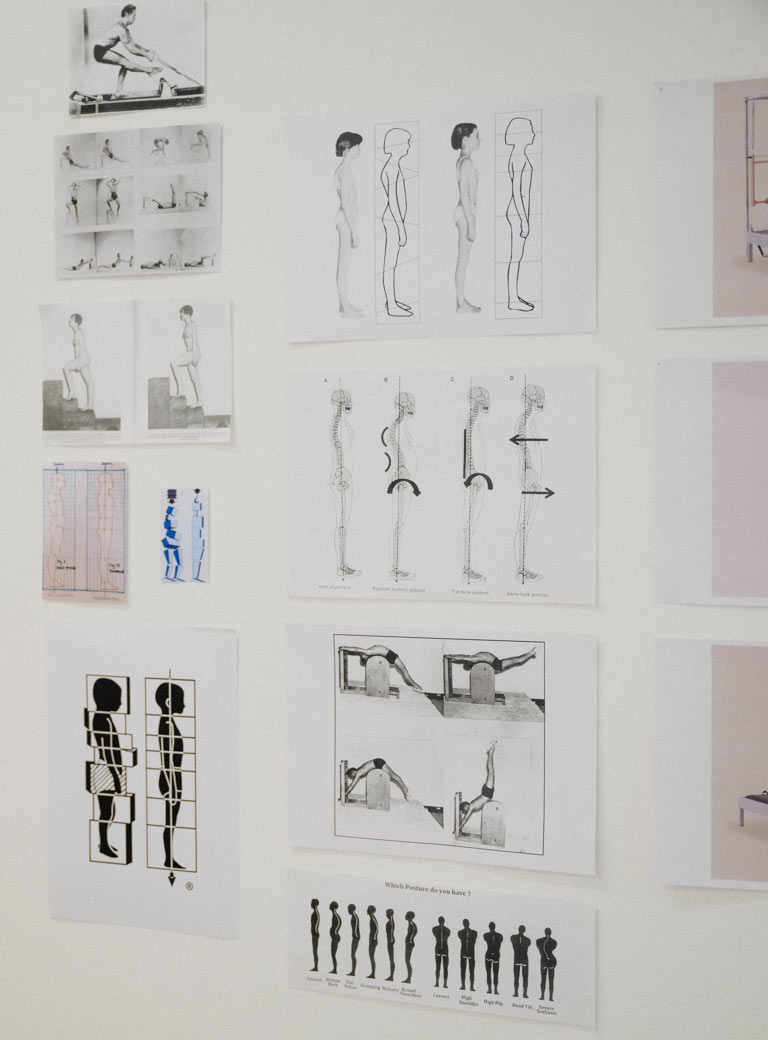

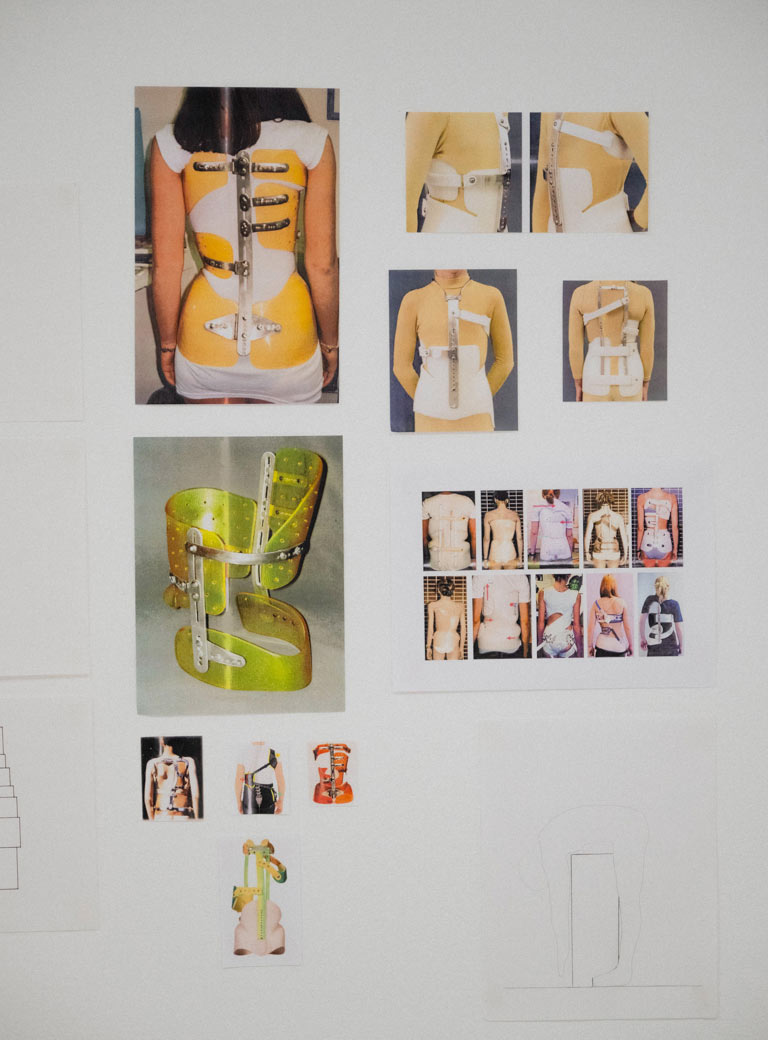

I would say the biggest turning point for me was working at a Pilates studio in Brooklyn called Zalla Pilates. Surprisingly, that's where I learned the most about sculpture. I became familiar with Joseph Pilates' teachings, but more importantly, being around the machines and observing how bodies move gave me a deeper understanding of posture, movement, and how physical pain and tension can be integrated into the body. The Pilates reformers—the machines—had a profound influence on me, not just aesthetically and material-wise but also in terms of their concepts. That experience significantly shaped my approach to sculpture.

How did you end up in New York?

I had always dreamed and fantasised about living in New York, like a lot of people probably do. Some of my closest friends were already living there, so I would visit them periodically and that only spiked my desire to move there. So I did, on a whim, and ended up staying. One of the things that attracted me so much prior to moving there, is that it felt like the ideal place for an extroverted introvert.

How did the time in New York influence you, your career, and your practice?

New York taught me about grit—endurance, motivation, staying focused. Being in such a pressure cooker, surrounded by so many people and so much energy, was electrifying at times and overwhelming at others. I was quite naive when I moved there, so it definitely toughened me up a bit. It can be a harsh place, but when you are open and in the flow, the most magical and absurd things can happen. Disappearing into a crowd can be a beautiful thing. And of course, the exposure to art was incredible. The museums and galleries are just on a whole other level. Living there was definitely the best education.

Was there a specific project or, or show that you saw that you would say influenced you a lot?

Yes, Richard Serra's Torqued Ellipses, the large-scale sculptures permanently installed at Dia Beacon in upstate New York. Seeing them in person was transformative—probably the closest I'll ever come to a religious experience.

What did you like about it?

The sculptures are massive, and the space they occupy is perfection. You can view them from a distance, but the real magic happens when you walk through them. Made from single slabs of steel, their weight and dominance create a visceral unease as if they might collapse on you at any moment. Walking through the sculptures, the walls begin to lean toward you, the space gets narrower and darkens and the coldness of the steel almost swallows you up. Just as the tension almost becomes unbearable, the sculpture opens up, the temperature changes and light radiates through the space, making the steel feel light and warm, and peaceful. A claustrophobic moment turns easeful within a few steps. And what struck me most was how Serra achieved such complexity within one sculpture using just a single material.

Would you say this theme is also reflected in your practice?

Yes, absolutely. While I would never dare to compare myself to Richard Serra, similar themes play a significant role in my artistic practice. I’m particularly interested in creating layered experiences within a single piece—works that can evoke discomfort or even anxiety, but then shift, perhaps within moments, to reveal a sense of lightness or flexibility.

How would you describe your practice in your own words?

The core of my work is about exploring how strength and vulnerability can coexist. I’m fascinated by the idea that these two qualities are not opposites or mutually exclusive but rather deeply interconnected and complementary. Finding ways in which tension can be held with ease is also very important to me. Tension is often seen as a negative or uncomfortable state, but when it is integrated, it can transform something precarious into something sustainable.

How do those ideas relate to your experience with Pilates and the philosophies of Joseph Pilates?

I’ve always been drawn to tension, but Pilates taught me how to work with it intelligently. I used to push and push to test boundaries and probe how far I could go until things would inevitably snap or fall apart. In Pilates, each movement is about simultaneously lengthening and strengthening the body. So when one side stretches, the other side has to strengthen to dynamically oppose the movement. This idea of dynamic opposition allows the body to expand with integrity and be adaptable so that a challenging movement can be held with ease. Pilates really taught me how to focus on balance, integration, and boundaries so that tension can be productive instead of disastrous. And that’s a crucial shift in how I approach composition.

How has your approach to selecting materials for your sculptures evolved over the years?

I've always been drawn to materials with a slightly off-putting or eerie quality—something that feels just a bit uncomfortable. I look for materials with that kind of subtle tension. Years ago, I discovered silicone, and it’s been a staple in my practice ever since.

What draws you to silicone?

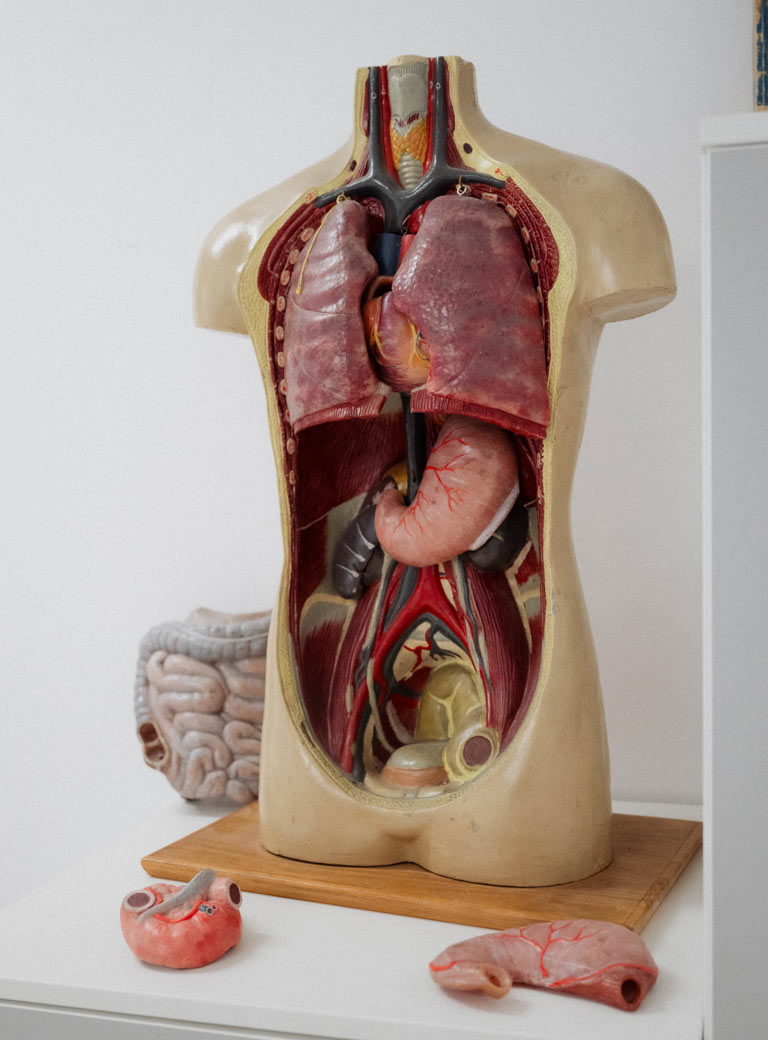

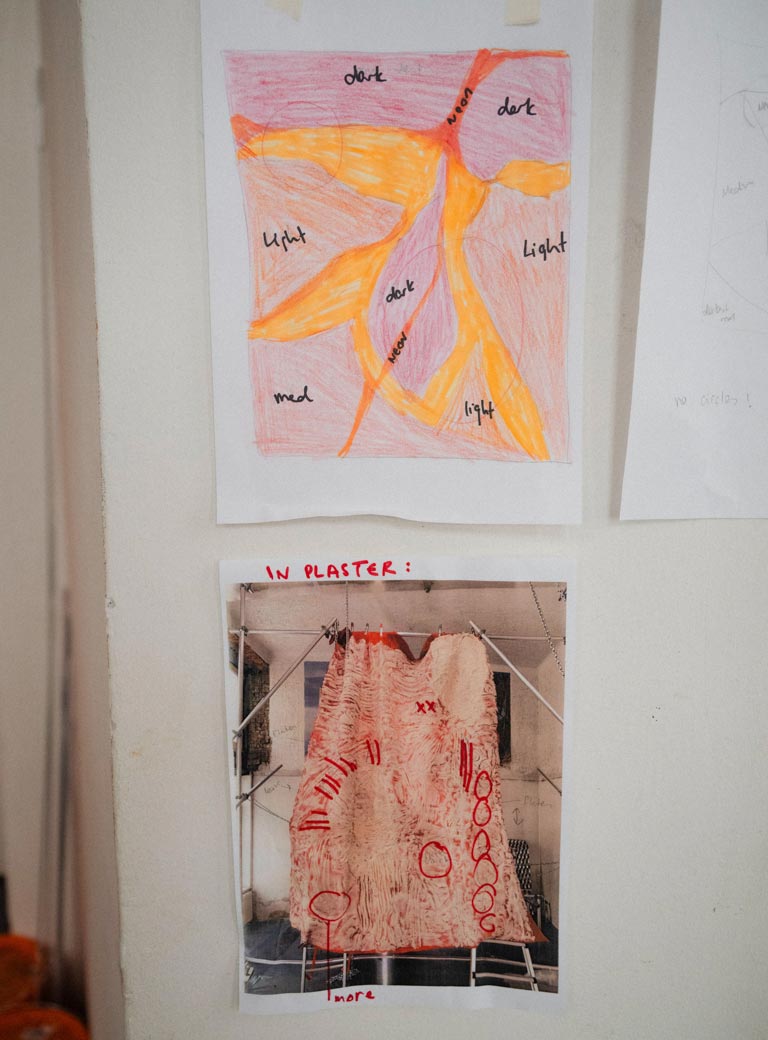

I’m drawn to silicone because of its flexibility and ability to absorb and retain the information it comes into contact with. I create compositions out of plaster that are movement-based, and when I apply silicone to them, it captures everything—the process, the actions, the memories. It’s like the material stores those moments. That’s what I love the most—it’s human fascia-like character. What’s also great about silicone is that it has a parasitic quality. It needs another material to bond to in order to become durable and not tear. So I combine it with poorly dyed fabric, which gradually changes the colour of the silicone over time. The fabric changes the colour of the silicone from the inside out, much like a bruise. This dying process can't be controlled giving the silicone an organic, living quality, even though it’s a completely synthetic material.

What about other materials like metal?

Since silicone is so flexible and almost oozy or jiggly, I like to pair it with metal as a counterbalance. Metal is rigid, structural, and has a clear direction. It provides a framework that helps give the silicone a more contained form. There's also a coldness to metal, almost a clinical or sterile quality, which counteracts well with the ‘organic’ nature of the silicone.

Would you describe your practice as intuitive?

Yes, absolutely. I think all of my work begins from an intuitive place. It often starts with a feeling or an impulse, sometimes something more complex. As the work begins to take form, it becomes more rational. But the starting point is usually something I don’t fully understand yet.

What emotions are you exploring in your work, and what are you confronting viewers with?

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly. The emotions I experience while making the work are often centred around longing, desire, and a sense of pushback. I am interested in that moment where you are unsure whether it’s about pain or release. Overall, I would say it’s about relaxing into discomfort and exploring it with curiosity rather than trying to push it away. Spending time looking at the underbelly and seeing what it has to offer, without dividing things into positive or negative, good or bad. I’m trying to lean into that duality and look for ways to bridge that gap so there’s less dissonance or confusion. Personally, I’m not a naturally balanced person, which is why I’m drawn to these themes. It’s a coping mechanism for me, but I also understand that discipline and freedom don’t need to be mutually exclusive.

How do you see art fostering self-awareness and externalising this perspective then?

I believe that in order to understand external structures, you need to understand the internal ones first. These two aspects—internal and external exploration or observation—go hand in hand, whether it's a sculptural structure or an emotional one. That’s why I’m so drawn to looking at things in this way. It’s about the idea that in order to relate to the outside, you need to be able to relate to the inside.

How do you approach creating environments that challenge the audience’s comfort zones while keeping them engaged?

I don’t always consciously realise I’m challenging people, as the materials are so familiar to me. However, when I become aware that something might be uncomfortable for the viewer, I try to work on quieter and more subtle areas, so they are more willing to come along for the seemingly more intense or challenging aspects of the work. I want to seduce and guide the viewer through the experience, so I think of it in terms of a choreography.

And would you say your art is sometimes misunderstood?

Once I’ve finished creating the work and it exists on its own, I think it’s fair game for viewers to interpret and project whatever they want onto it. Every person has their own visual experiences and associations, so hearing how my work is interpreted through their individual lens is really interesting to me. Keeping that space open feels important.

Are there any recurring responses you hear from people when they view your art?

”Wow, this is gross” would probably be in the top three reactions I get.

Do you like hearing that?

Yes, I think it’s lovely. It’s great. Other top responses are, “Oh, this gives me the shivers...” , or “Do you like eating meat?” People really want to know if I love meat, which I don’t. I really like that response. Another one is, “Why do you choose such ugly colours, you should use blue?” I’ve heard that a lot. But I can understand it, as the colours I use aren’t always very “living room friendly.” But the best responses are when someone can articulate something in my work that I have felt but haven’t been able to verbalise yet—that’s a wonderful moment. That’s why I try to stay open to feedback. I don’t think my work is misunderstood, though.

What are your next projects?

My next project is an exhibition at Kunstraum Dornbirn, which will be on view from March to June of 2025. I’ve been working on it for the past few months.

What challenges have you faced working on this project?

The challenge with Dornbirn is that the space itself is so beautiful—it almost doesn’t need any art. It has a church-like, industrial basilica feel, so my first task was figuring out how to work in dialogue with the space without trying to be in competition with it or be completed overpowered by it. The scale of the project was another challenge. I’ve never worked this large before. I knew I wanted to build freestanding structures that wouldn’t rely on the walls or ceiling and could create a closed system. So the biggest issue has been anticipating static challenges, especially since the silicone is quite heavy. Viewers will be moving through and under the structures, so ensuring that everything is secure is obviously very important. It’s a little nerve-wracking, as I’ll only fully see the work once it’s installed.

How do you approach and incorporate the influence of spaces in your work, and what does it mean to work site specifically?

Working site specifically is my favourite. I really love reacting to spaces and being in conversation with them. Each space has its own personality, tone and restrictions that I find very inspiring. For example, Kunstraum Dornbirn is industrial and huge so it feels more like designing a big set. Making this work has been quite performative and extroverted. In contrast, the work I am making for my upcoming show at Zeller van Almsick in April is much more intimate. The gallery looks like a traditional Viennese apartment and reads more like a private and domestic space, so it will bring out quite a different mood in my work. I am really excited to be able to have both of these spectrums on display at the same time.

What drives you to continue with art?

It's probably my curiosity to really get to know myself. Each project is like this time capsule and it’s such a cool experience to be able to take a step back and have this unique vantage point of your subconscious. That makes me want to dig deeper, push further, and get weirder.

Interview: Livia Klein

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt