The Austrian artist Stefanie Moshammer uses various media such as photography, moving images, text, installations, textile sculptures and book publications to elevate her personal experiences to an artistic level. Through her research-based practice, she offers viewers a fresh look at social issues such as female alcoholism, the search for and marketing of love, or consumer behavior. In addition to her artistic work, Moshammer is also in great demand as a photographer for fashion spreads; she has worked with Harper’s Bazaar and Fendi, for example.

Stefanie, how did you get into art?

I actually started out with textile design; then I spent a year studying social and cultural anthropology at university to add a different kind of input. Later, my focus shifted to graphic design. However, my respective application at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna was not successful – I was quite outraged (laughs)!

Why were you rejected?

When I inquired, I was actually told that I would be better off in a photography class! I eventually studied at the University of Art and Design in Linz, where fortunately graphic design and photography were taught together. My final thesis there was my first artistic work. I went to Las Vegas at the time, and that’s how the book Vegas and She came to be.

What was Las Vegas like?

It was a crazy, terrible, but interesting place. Because it represents such a break: it’s this artificial, dreary place where people try to sell you happiness. The title Vegas and She came from the idea that Vegas is the male counterpart to She, to the women who expose themselves there, but also to myself.

Personally, you didn’t get lucky in Las Vegas though – didn’t you spend time in jail?

Yes (laughs) and the book Vegas and She contains some hints about the incident.

How did that happen?

That’s a stupid story, one which I’m not going to tell (laughs). But that was part of my Vegas experience. Funnily enough, I met people in jail whom I had photographed before. I was sitting at this long dinner table, and suddenly there was a woman opposite, whose photo is included in the book. But all of that gets booked onto my experience account (laughs)!

How was your work process for this first book, Vegas and She, which came out in 2015?

I would say that I still had a naive approach to photography back then. I had no expectations of myself. I just took a lot of pictures, without really knowing what would happen with them later. At the time, I was still taking analog and digital photos; Vegas and She is the only work for which I still took analog ones. Meanwhile, I find them to be limiting. For me, the post-process is more exciting: being able to choose, edit and curate the images from a huge selection.

So your actual work process begins once the photos have been taken?

Exactly. That’s when I think about how I can put the images into context, what I want to tell through them: it’s visual storytelling. That’s why I do books, because they offer a continuous narrative.

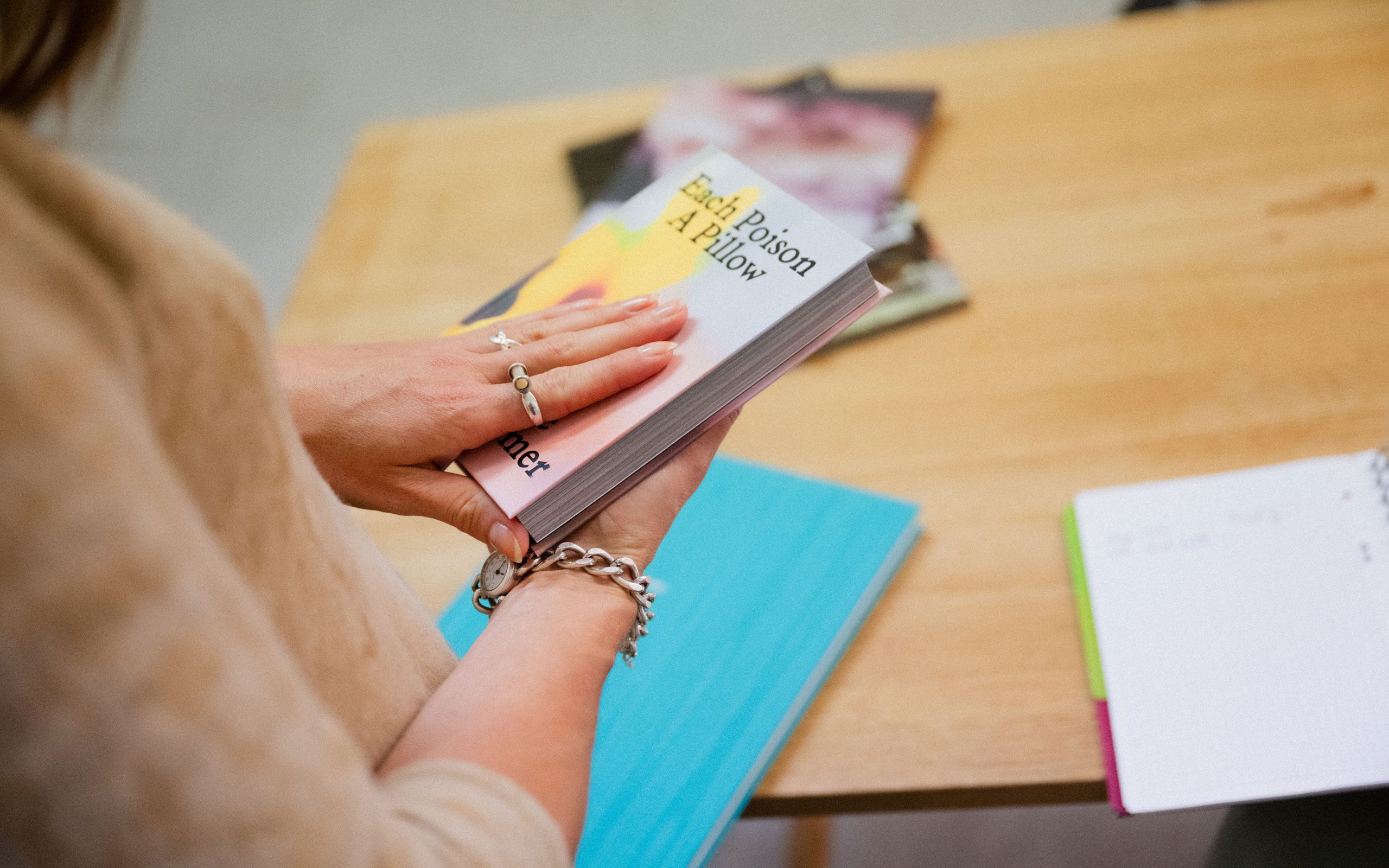

Which book is your most personal one?

Maybe the small format Each Poison, A Pillow. The origin of the work is my letter to the “Christkind” (the Austrian pendant to Santa Claus) as an eight-year-old, in which I ask for my mother never to be drunk again. However, a lot of research went into the composition of the images for the book; it’s mainly found footage, only a few of the images were taken by myself. But my letter is the starting point of the work.

What does the book contain?

There are, for example, historical and contemporary advertisements for alcoholic beverages, where women are usually portrayed in a sexualized way. Video stills and personal photos from our family album are mixed with Instagram screenshots of videos in which drunk women stumble around. There is this personal theme of growing up with an alcoholic mother, and at the end there is a text that my mother wrote. The small book format reflects the context of intimacy, as well as the idea that the topic of female and familial alcoholism is mostly a hidden one that often doesn’t get much attention.

Are your works like chapters of your life – the time in Las Vegas, the confrontation with your mother…?

Well, certain topics engage you at certain times. However, I don’t just try to tell individual stories, but I like to elevate them to a more general level.

How do you accomplish that?

Through research. I want to understand what aspects, apart from the personal one, also make up a certain topic. Each Poison, A Pillow was the first time I made my working approach transparent, for everyone to see. The beginning of my career was about taking photos, and I only worked with purely visual material; that is a little different now.

Did you feel that photography alone wasn’t expressive enough?

Yes. The photographic image has a limitation. But depending on what you want to say, you can enrich it with other media. That’s why I like to use video installations or even other materials in a more installative way.

Was Each Poison, A Pillow the first work for which you combined different media?

Yes: it is a book, but also an installation. In the exhibition, for example, there were video works; and private archive photos were printed on cushions which were placed like sculptures around the room. Female alcoholism is a domestic phenomenon, and that’s what these pillows refer to, having something soft, relaxed about them. And the same goes for every substance: this search for comfort.

Do you stage an exhibition for each of your books, or produce a treatise for each show?

Not necessarily. But through the books, I reach different circles, my work travels to other places and into other hands. At the same time, it’s a closed format, like a small world that opens up. An exhibition is always limited to just a certain period of time, but the book survives for much longer.

One book that led to a respective show was Vienna, your commissioned work for Louis Vuitton. How did you portray the city your own way?

At first, I found it difficult, because Vienna is close to my heart, and I wanted to avoid stereotypes. Then I immersed myself in research: I used song lyrics, screenshots from my desktop, and emails from the editor revealing the creation process. At first, he wanted Vienna to be portrayed in a more clichéd way (laughs)! But he finally understood my idea of including my research on the city in the book. So I broke or subverted the rules, while still fulfilling them in my own way.

Breaking rules: This brings us to the background of your artistic work. What makes your photography art?

That’s not my decision. It often happens through institutions, through a certain view from others. It’s a difficult question, to which I often don’t know the answer myself.

Doesn’t the artist’s intention also come into play?

I think you can say all kinds of things, but if you don’t bring your work into the world and present it, whether as an exhibition or as a book, it won't be noticed. It’s the confrontation and occupation of other people with it that makes a work become art. I rely on the perception of the viewer. Of course, I have certain ideas and content that I try to convey in my work, but in the end, I cannot know how it will be perceived by someone else.

What topics do you want to communicate?

I’m interested in topics that carry a certain social break. I try to portray them in a poetic way. So that the “ugly” is not immediately apparent but can be perceived through my work. Issues such as the mystery of certain places, the (fictional) search for love, the omnipresent influence of capitalism and the phenomenon of our consumer behavior, including alcoholism, are topics that engage me. This content is then intertwined with personal narratives and experiences, which adds depth.

You are mentioning the influence of capitalism; however, you worked with Louis Vuitton, a very commercial company…

But here, too, I always try to break the rules in some way and give viewers a different perspective.

By always using your own, unique aesthetic – how did you develop it?

It happens organically: you just find your own language. I open up my inner self to the outside world. And what my work is like has a lot to do with what my story is like, what I am like, what my character is like. That’s why every artist’s work is different. It’s an extension or continuation of your own persona, which is what makes it so exciting. You often don’t know exactly why you are the way you are and therefore don’t know why the work looks the way it does. Of course, this also has a lot to do with external influences.

Is your work a mirror of yourself?

In a way, yes, but when you make art, it’s not like you’re constantly looking at yourself in a mirror. The work goes outwards. I find it very difficult to evaluate one’s own work.

Speaking of evaluation: as an artist, do you have to put yourself above what others might think once you put your work out for everybody to see?

You definitely have to stand behind it! It’s important to me to imbue human issues with a certain dignity, a sublime look. But of course, I do make myself the most vulnerable with the theme of alcoholism in the family.

Although many other people are being affected by the same problem…

Yes, and that’s probably why I did it. Because I do know that it’s not just an individual fate, and because I do not feel any shame in this respect.

In your works, you mix truth and fiction. What is the relationship between them?

The two overlap and I love to play with them. My work always stems from a certain “truth” in which I refer to a real event. That is my scope that gives me room for experimentation. Then I add a fictional element that charges the story. In my work, reality embraces fiction; you can’t have one without the other. You need fantasy to make reality more bearable. At the same time, humor and irony always play a role in my work.

Do you see art as an escape?

Escape would be the wrong term. Rather as a certain enrichment of reality, which flows into fiction in a tender way.

How does your commercial work for fashion companies differ from your artistic work?

The main difference is that a commercial contract takes much less time. I often find this shortness refreshing.

And commercial work is probably less demanding in terms of research?

Well, you can also build a world with fashion, clothing or textiles. But a much more short-lived one of course. As much as I like it, I couldn’t just do commissioned work. Because I often have the feeling it’s a kind of work that lives and dies quickly.

But even there, you often create memorable images!

Maybe it’s just to me that it seems so short-lived (laughs)!

Do you have the impression that the reputation of your artistic work might suffer if you also do commercial work?

I used to ask myself that a lot, but not anymore. And the commissioned work is really well paid (laughs)! That in turn makes me less dependent from this complex art business. I enjoy having several levels to make a living from my art: The commissioned work, the visual arts, and I teach from time to time. All these ventures are equally important to me.

How do you like working in Vienna?

The advantage for artists here is that a high quality of life is associated with a relatively low cost of living. But I find it problematic when everything revolves just around Vienna. It’s important to get out, especially if you want to be noticed internationally. I live between Vienna and Paris, which works well for me.

What new projects are you planning?

I work on a couple of projects at the same time. On the one hand, I’m continuing the work on Each Poison, A Pillow. I’m also currently reworking a past project: The series I Can Be Her had as its origin a letter that I received in Las Vegas, from a man who had come to my house and then suddenly wanted to spend his life with me. What he wrote was very bizarre, full of artificial romanticism, about houses and cars that he could offer me. My series of works then was my answer to his letter at the time. Ten years later, by chance, there has been contact with the man again, which in turn leads me to try to rearticulate the work.

What exhibitions do you have planned?

Each Poison, A Pillow will be presented in September 2024 with Kahan Art Space during the Parallel Art Fair. And I’m currently working on a book with the art publisher RVB in collaboration with Belmond. Excerpts of it will be shown at the Dover Street Market in Paris in November 2024. Until September, a work of mine can also be seen as part of the exhibition Critical Consumption at the MAK in Vienna.

Slow Growing, 2023, 8 x 30 cm, glass, stone

Pretending, 2022, glasses, colored liquid, variable dimensions

Some Nights Are Red 3 + 1 + 4, 100 x 130 cm, ink on canvas, acrylic paste, stretched onto wooden frame from Each Poison, A Pillow

Site specific installation, fabric, leather, filling, elastic, Gallery Miroslav Kraljevic, Zagreb, 2021

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt