The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

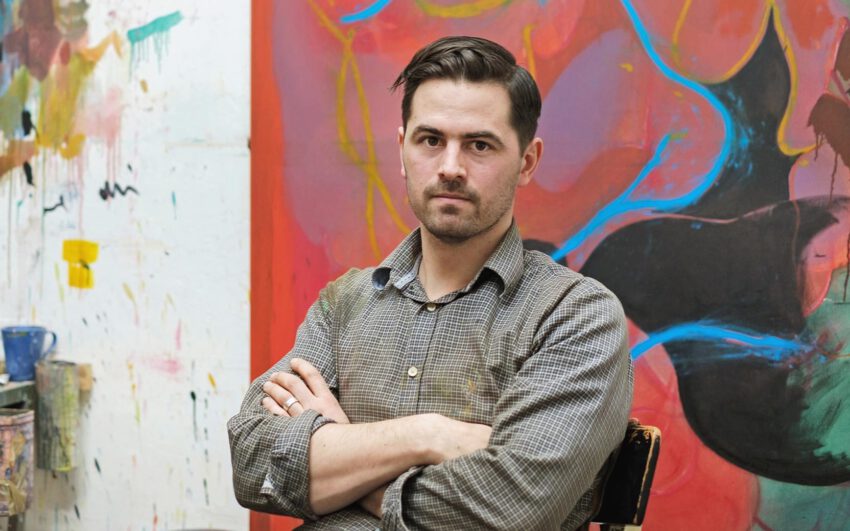

At first glance Tal R’s exuberant colorful paintings may give the false impression of being childishly simple. Looking closer, a subtle complexity emerges from his work. What appeared joyful and playful suddenly draws the viewer into a world of myths and darker themes. “It’s fucked up,” says the artist bluntly. We met Tal R in his Copenhagen studio Paradise, where he talks to us about topics like the beauty of failure, about his initial struggle to live out his artistic talent, and about what he wants viewers to take away from his work.

It seems as if we were in paradise. A great aura emanates not only from your studio, outside your studio it even says "Paradise".

Oh, thank you. A print studio by that name was formerly based in this building and published a communist newspaper with the title Land og Folk (Land and People), which had quite a reputation in Denmark. The studio was also well known among artists for printing cheap posters. When I moved in here, I liked the concept of working in a Paradise, so I decided to keep the letters outside.

Your personal paradise – that sounds fascinating. What is it that is so paradisiacal about your studio?

For me, any studio is a precious place. I like to compare it to the brain. If you think about it, your own brain, despite all its shortfalls, is the only paradise you have. In your brain you are free. You can kill anybody, and you can fuck anybody. You do things that you won't do in your real life, because you would have to bear the consequences. A studio is like a copy of the brain. It’s a place where you try out various things, where you have permission to fail. I think that art is probably the only field or discipline where vulnerability is thought of as a good quality. That’s one of the things that make art special. And that’s why my studio is so important to me.

You’ve been a teacher at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf for nine years. Did you carry the idea of having the permission to fail into your teaching concept?

When I arrived in Düsseldorf I didn’t bring extensive pedagogic experience apart from a short teaching period in Hamburg and one year as a guest professor in Helsinki while I was still a student. However, it somehow became clear to me that, in order to create a good class in an art school, it is important to create an environment where you are able to make mistakes, read your mistakes, discuss mistakes, and fish in them like in a pond. I think you should do exactly that: fish in your own mistakes and even those of others. Your education starts with disappointment and destruction. There is so much to learn if you fail in a grand way. It helps you grow, to reach another level. What happens at the academy is exactly what must continue in the studio.

The spectrum of your work is very wide. Your clear focus is paintings, but you are not restricting yourself to this medium. And a lot of topics can be discovered in your work. How would you describe the art you are creating in your own words?

I think entering my work feels a bit like entering a Luna Park. There’s the roller-coaster, there are shooting galleries, and of course the candy floss van. There are all these different tents with different things. At first glance, it might look like I make very different types of works. But if you look closer, I think most people will see that they are all very connected. The unifying element is the way I work. I fish in what I’m seeing.

Can you give an example what exactly happens when you "fish" in what you are seeing, as you say?

Let’s say that I am drawing flowers on the table. I look at them and say, “I want to draw these flowers,” but while working I notice the possibility of letting the flowers become more ornamental and no longer being the main subject. Or the idea imposes itself to just forget about the flowers altogether and to extract only certain elements of them, transforming them into something abstract. You know, in our culture the artist always gets help from the viewer. I mean the viewer has learned how to look at things in a painting. So, for example, he can tell the techniques, which make something look like it is near or farther away. How much can I ask from the viewer? I think I can ask a lot, actually.

What exactly are you expecting from a viewer who stands in front of your work?

If you approach my paintings you will usually find something very concrete and figurative. Something you can describe to someone over the phone, using simple words. Then, at closer look, you’ll discover something awkward – something sticky. It is a bit as if you would walk a staircase. Suddenly there is a missing step and you are in mid-air. Something that looked playful and happy at one moment can have a weird other reading. It can turn into something disturbing, even uncanny. For example, I could paint a man walking on the street. He has a hat on. His reflection can be seen in the window of a bakery. This is what everyone would see and explain to someone else. But, after looking at the man with the hat and his reflection in the window for a while, you are becoming unsure what you are actually seeing. Looking closer, the reflection in the window is wrong. Something seems to be missing. Things seem to be getting out of hand. It’s like you have an ice cream in your hand, and suddenly it starts melting in front of your eyes. My way of working is actually very basic. It’s fucked up. (laughs) Another more cultivated word for "fucked up" is abstract. I want people to enter the unknown.

You are known for incorporating many different elements into your work – a mash-up of different impressions.

Do you know the word “kolbojnik”? It is Hebrew and means “leftovers”. I think that describes very well what I do. I am just fishing for a lot of stuff that already exists. It is a constantly evolving series of impressions I pick up. It’s things I see around me, little details I discover, like the fabric of the tablecloth in a painting. If you combine different impressions what you get is a weird object that’s beyond language. This sculpture here, which looks like a spider, is actually derived from a drawing of clouds reflected in water. On the wall here, these are all notes and drawings, which try to capture my impressions and the connections I have made. I am the only one who can actually read them. But, after a while, even I can't remember anymore what it was about. It is a lot of information circulating in a state of flux.

So by creating combinations of previously disconnected impressions you intentionally create a world that escapes reality.

Yes, I think so. I want to create something dreamlike. I think it is really interesting when people talk about their dreams, it is not about things that are actually happening. Dreams break down the conventional concept of space and time. That's the amazing thing about dreams. Art is very similar to this. It is able to reveal certain aspects of human nature that other disciplines can’t. That is what makes it so important for society, because it is the "ghost" in the machine.

Among your best-known works are block-prints. What is it that fascinates you about this technique?

I am attracted by the fact that the result is not fully predictable. We carve the wood blocks ourselves, using old chopping boards from kitchens, which we find at flea markets. All the marks you can see here are from people who have chopped things. Also we rub in the color manually with a spoon, which is a pretty tedious process, but this way you let in the unexpected.

How do we have to imagine Tal R approaching an empty piece of canvas?

Most of the time I just sit in front of a painting trying to find alternative approaches which challenge my own preconceptions. In this instant I am struggling down my previous expectations and everything that has been on my mind. I am not saying you should not stick close to your intention, but you should keep at a certain distance from it. I feel this tension is constructive. You should allow yourself to be halfway directed by the painting. And halfway you should explore your personal desires and work out what is necessary to make the painting come alive. In a way it is like a conversation. What you really want at the end of the day is to surprise yourself, just like you are making unpredicted steps on a dance floor. I usually focus on just one painting at a time and finish it in one go.

“I think entering my work feels a bit like entering a Luna Park. There’s the roller-coaster, there are shooting galleries, and of course the candy floss van.”

Despite your great international success today, you were struggling to find your way in the early beginnings.

I think very rarely you leave high school to say, “I want to become an artist.” And if you do so, you are actually asking for trouble. Knut Hamsun, the great Norwegian writer, is reported to have said in his youth, “I want to be a writer,” and an older writer replied, “If you want to be a writer, go travel.” I think there is much truth in it. You need to run away, try yourself, and hit your nose until it bleeds. My journey was very similar to that.

Can you tell us a bit about your own struggle as an aspiring art student?

You know, for me, drawing has always been a natural thing. It felt like dreaming at night: you don't decide what to dream about, you dream about what you need. In the same way, you don't draw what you are supposed to, you draw what you need and you don't question its function. Until I went to art school, I never thought of drawing as being art.

The moment I walked through the art school’s doors drawing was considered art. It changed everything. All of a sudden there were forms and rules to follow. Everything that had to do with drawing left me, immediately. It was almost in a biblical way. I walked into art school, and art walked out of me. I was struggling for ten years, until I was 28, and several times I ran away from this thing called art. I wanted art to be what I remembered it to be as a child: Just doing what you needed to do, losing yourself in the things you are full of.

After frustrating ten years, and after I don’t know how many paintings which I started and never finished, I found out that frustration can actually be good energy. It helps to talk to one’s own disappointment and to accept it as an innate intelligent force, as a critic and a coach, who enables you to improve. I call it my rejecting demon – the Devil in me. He is my best professor. A clever bastard.

You don’t use your full name. You are using the abbreviation “R”. What's it all about? What does it stand for?

I grew up in Denmark as the son of a Danish mother and a Czechoslovakian father. Tal is a traditional Hebrew name. In Danish it means “number”. It is not a name. Also the name “Rosenzweig” was unheard of during my childhood years in a homogenous country like Denmark. Even today, people have difficulty pronouncing and spelling my last name. Therefore I reduced my last name to R.

Peculiarities like these added up for me as a child giving me the feeling that I didn’t really belong. In Denmark I had the right looks, but my name estranged me from other children. In Israel, my name was right, but it didn’t fit with my broken-Hebrew and my Danish looks. At a young age this is troubling. You just want to be Michael, or Klaus. And you want to belong.

As I grew older I became more comfortable with the idea of being different. I even found that there was merit in the idea of not really belonging anywhere. Because it allowed me to both be myself and at the same time to become an observer of myself. I found these two pairs of eyes quite useful as an artist.

Looking back, when did you make your first big career step as a young artist?

It was probably with my first institutional show. Anders Kold was a curator at the Aarhus Kunstmuseum at the time. He was like a mole who would dig through art scene events and never miss an opportunity to go to even the smallest openings. He was among those to follow my development early on. In 1999, he offered me to do my first museum show. In the meantime Anders is head curator at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. We have become friends and remain closely in touch.

You have been part of the global art circus for a long time. How do you deal with that?

Sure, I am part of it. All the time all kinds of people visit. And of course the galleries are demanding new works. Every artist needs that. It would be untruthful to say that I am not doing art for other people's eyes. But you have to keep your work out of the circus, at least until it leaves the studio. My studio belongs to me. When I work here I shut out every influence and the studio becomes its own autonomous world. I'm not saying that I am against the outside world, but this other world starts soon enough. In the studio there is no room for strategic thinking or cool calculations of what’s to become of the work. It's mediocre thinking, and I have absolutely no respect for artists who let themselves be distracted in their work by how well their works perform at auction sales.

Curators play an important role in this "circus".

When I entered art school, I heard the word curator for the first time. I had no idea what they did. I still remember how I thought: a curator is to an artist what a butcher is to a cow. He slices you up. (laughs) Curators play an essential role. They find a language so people can relate to art. Curators are mediators between an artist’s studio and the outside world.

Is there a piece of advice you can pass along to young artists with their career still ahead of them?

As a young artist you are still pretty clueless about the art world. What you are attracted by are those artists who you have come across and who you know well. So my piece of advice is to not settle with what you already know, but to always look beyond. My mother once took me on a bus ride to the Documenta in 1992. I was 25 and still very young as an artist. And I remember it as a truly eye-opening experience. It was the first time that I saw people like Luc Tuymans, Franz West, Jonathan Lasker, Eugène Leroy. At that point I couldn’t say that I liked their work, but they got me confused in a great way. It just opened my mind. I remember looking at Franz West and how clueless I was about his work. I could not quite take him serious. But it stuck with me, like chewing gum under my shoe. And that is actually what art should do. It shouldn't necessarily be that you love it. It is the chewing gum under your shoe that is important.

What are you working on at the moment?

As you see there is a lot to do. I am preparing an exhibition for Villa Schöningen in Potsdam that will open in a couple of weeks. There will be a two-part exhibition together with Mamma Anderson at Gallery Bo Bjerggaard in Copenhagen and Gallery Magnus Karlsson in Stockholm. For 2017, I am preparing a comprehensive mid-career survey at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, outside Copenhagen, with Anders Kold.

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer