Thomas J Price wants you to see things from a different perspective. His work, ranging from performance art to animation to painting to sculpture, seek to reconfigure our physical relationship to objects. To have conversations with ourselves about how we interact with the world around us, what we trust and revere. Better known for his large-scale figurative sculptures, there are many more dimensions to Price’s work, and his constantly critical perspective.

Thomas, what were your artistic beginnings?

I am very lucky that my mother is thoroughly creative – she studied textiles at the Royal College of Art. I was taken through the world in my formative years by this person who saw the magic in everything and had questions about everything. That made me feel able to question and wonder at things myself. Everything became like a playground. I have two brothers and we were taken to museums from a very early age. I have this show at the V&A, which was one of the places I came to as a child and one of the museums I have been critiquing and referencing throughout my career. Why is that there? Why is it that nobody looks like me or my brothers, or anyone I know here?

Were there any particular artists that you were interested in at that time?

I was very interested in Classics. In the V&A, one of my works sits below this painting of Phidias which I only noticed, during the installation. Phidias did these huge sculptures and temples which was an influence just in terms of the ambition and of it being a national focal point. But then I was also looking at Giacometti, as the concept that I was really interested in was space. The way that Giacometti used objects to talk about the way that we experience space and distance, and how perspective can seemingly shift as we move around the object.

Were there artists you were reacting against?

A lot of my friends described Picasso as a genius. I never liked Picasso, I always thought – “that’s just an African mask on a white face.” These things started to dwell on me. I think of things that were said to me in relation to race, or were insinuated, while I was getting through secondary school and art school. I found that the art world, as I understood it, quite closely mirrored society in terms of the structures within it, who got to benefit, who was plucked out and placed in a high status. I think this is when the idea of the plinth became interesting to me. I was told, when I went to art school, not to use plinths nor figuration - that was done. I had gotten into the Royal College of Art based on my animation and video works, and a performance piece. Then I started working on figures, in a broader attempt to connect people to the thing that I was trying to make them look at, leading them to think about the way they interact with people around them.

When did your interest in sculpture develop?

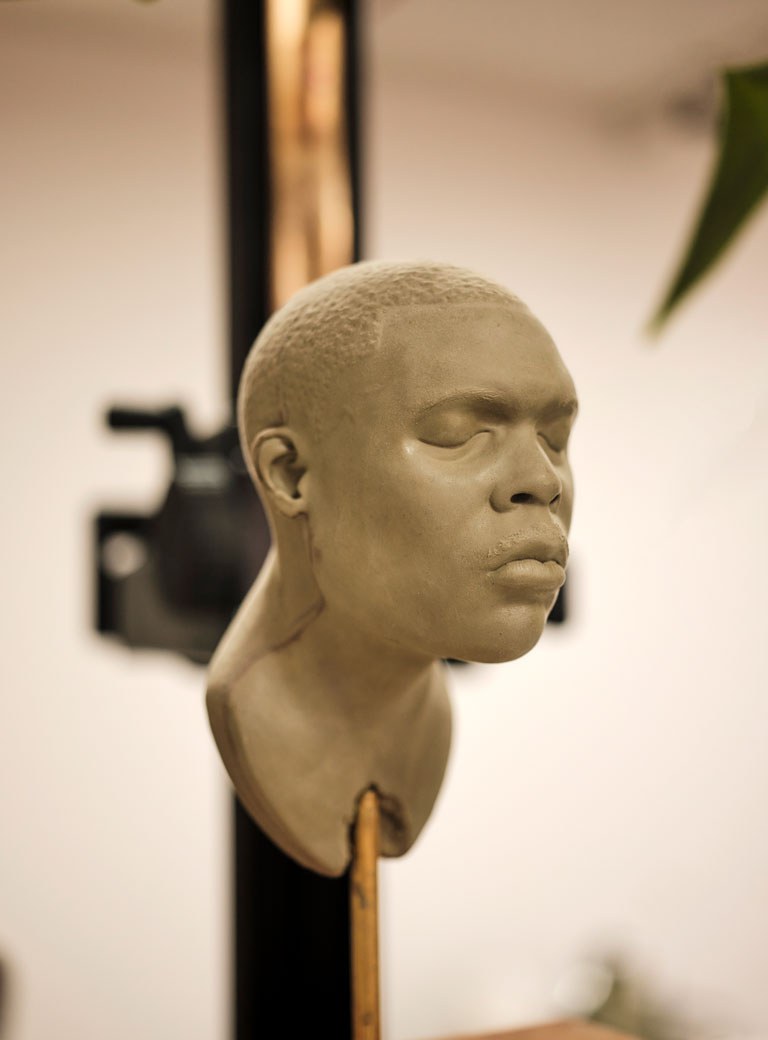

When I was a kid, I remember walking with my mum and my younger brother in South London, and I remember looking up at the Moon and getting the sense of like, “shit!”. Because it was so full, I could see it as an object. I knew that the Moon was supposed to be this huge thing. I felt like I was going to cry because I did not know how this was possible. It made me question what we are in this world, and I think good sculpture can do that too. It can make you so aware of your relativity in a world that denies you the time to think about that essence of being. I was also drawn to material, like clay for example. I love keeping it warm in my hands, spreading it with the thumb - it’s this tactile, almost therapeutic experience. How people understand materials too, bronze is an obvious one, where they carry a psychological impact. I love to try and harness the relationship between materials and expectations, of what those materials are supposed to be associated with or function as. Aluminium, the material for the Numen heads placed on marble bases. I love the game. This infinite arrangement of things.

It’s important with sculpture to be in the space and experience it, but in a number of your sculptures the figures are holding a smartphone and are looking down at the screen. Why is that dissonance of interest to you?

For me, the phone has always been this incredibly powerful symbol, this emblem of potential for communication. In a similar vein, when you have potential for something, you also have the potential for the absence of something. The first time I used the phone was in a stop-motion animation. It was not a mobile but an old-school-style telephone. There is this guy in moody lighting and he is lip syncing. There is no audio, so you don’t know what he’s saying, but you do see his expressions. Using the phones means that while the figures are by themselves, they are connected. The idea of miscommunication is very interesting to me - how people say things about me that don’t resonate. And I must be doing that to other people, so we are all doing this to each other. The phone also sets my figures apart from the Neoclassical and the Ancient. They are holding a spear or a shield or whatever, and mine are holding a phone, but we are standing in the same way. It’s connected, but it is different. That pose looks so nondescript and simple, but it is actually incredibly complex and ambiguous.

Nowadays most people are looking at art in galleries through their mobile phones. Do you think about how people are photographing your works?

Photographing sculpture is a particularly interesting problem. With my animation, that’s what it is. I love that transformation of 3D to the two dimensional, what can be understood as a tactile object in our heads, and for me that loop of comprehension without the fulfilment of touch is super powerful. It is talking about absence again. When I create a sculpture, I’m not ending the sentence. I’m giving people the agency, the power to continue writing, to connect and be involved. And people create something far more powerful than the artist can do. So when it is processed through a lens, through the process of photography, it transforms the object into something else.

There’s a tension between what is ordinary and what is extraordinary in your work. The figures might look quite ordinary, but they are massive. How does that play out to you?

Scale is such an interesting thing to work with. It's another material really. The impact that has on people. The first sculpture I showed publicly was a very small head Mixed Feelings about Bus Drivers which was using plaster as a means of commenting on the value of marble. The important thing was that the character was fictional, he was not trying to dominate or smile or look pretty. Everybody has a resting face, although we don’t tend to know what it is. So it is therefore non-performative. There’s a power in that freedom to not have to smile for an audience, to make people think that you are safe or happy – basically performing the role that you have been given by society because of what you look like.

How did you achieve that through your first public sculpture?

It was challenging social expectations, but also expectations of artwork forms and what a monument does, and what scales a monument. How high up is it supposed to go? I placed mine on scrap wood, low down on the wall, so that it moves the viewer to have to look at it. That is how I got into the physical world of sculpture. It invites questions about who in society we are supposed to value, and keep valuing, and coming to the realisation that their narratives are fictional. I really got into this fictional quality, which then allowed me to take elements of poses or dress and reconfigure it into what I see around me. This idea of the everyday. But the everyday is extraordinary – if you look at it through the right lens. Art can do that, through playing with scale. It can change your viewpoint on things you take for granted.

What is your process for creating sculpture?

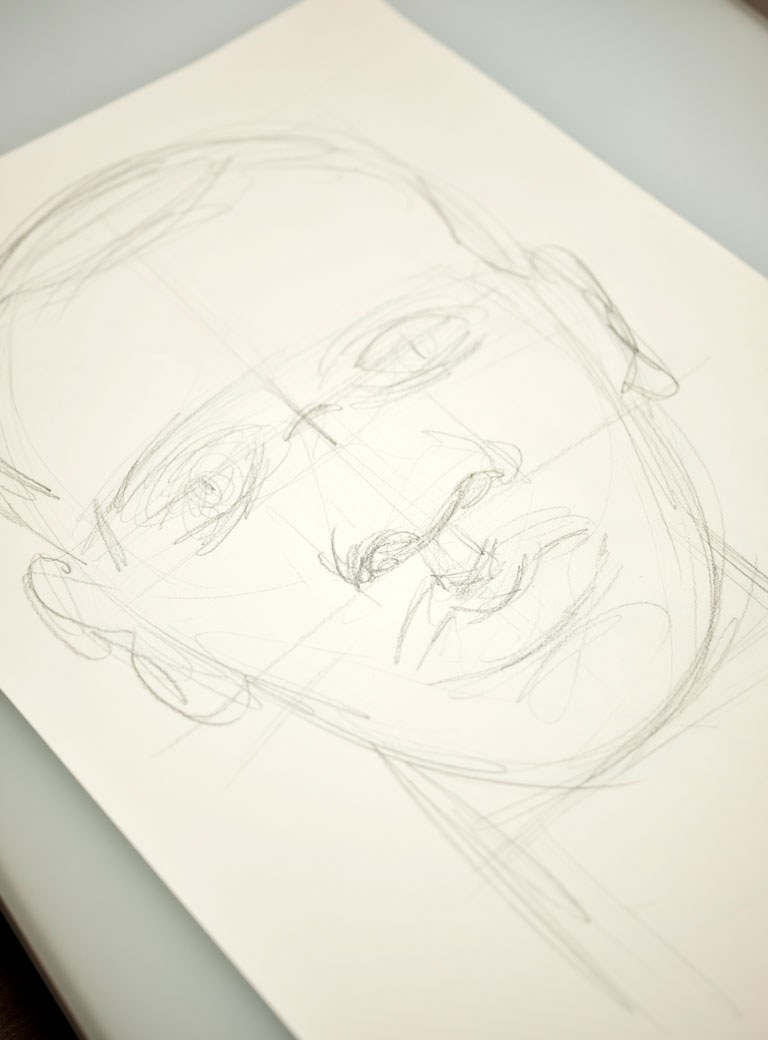

It shifts. I used to spend lots of time sitting in front of a tin-foil armature and apply clay slowly, with references around. The works were made around this emotional framework. And now, with a few more miles behind me, I draw upon my own works in a way which is quite freeing. It’s still based on a feeling, and on trying to elicit a response in people. The consistent point of reference is myself and the considerations that I have about these sets of visual cuts in people and the context, such as where they are going to be shown. I will use digital sculpting, which is a more multi-stranded set of possibilities. It has allowed me to zone in on nuance. Then that is printed out in 3D. I only use that software as much as I need, I use it as digital clay. My composites are made on the software, I upload it, but then I still need to be able to understand it as a physical object. I then work with foundries to go through this very old process of wax casting. It’s a very composite process of recently developed and ancient technologies.

When you are putting together the composite, is that from people you are scanning?

Yes. I feel like Frankenstein! The idea is that it is a rejection of individual exceptionalism. The idea that generals and politicians have a true narrative or story is ridiculous. That is what people find easy to believe in and they want to get behind these national stories. I spent some time in Rome with archaeologists, looking at digs and then putting them together in a museum. The truth is that these people don’t know who those figures are, they just found bits in a local area and put them together and then say, “Ah, that must be Apollo!” because he’s got sandals on, or something. Then it becomes official. It’s in a book, it’s in a museum. That’s a microcosm for the world. What other stories have been fictionalised?

Is there a work in which you directly explored that idea?

I did a piece commissioned by the Studio Museum in Harlem, and it’s a guy on his phone. I called it The Distance Within, because it was about the distance between the intake of what’s on that screen but also what that creates within us, the distance we have with ourselves, the things we know to be true, and so on.

You said earlier about going into the V&A as a child and not feeling any kind of representation in art. How much does that drive what you are creating?

I think it’s a huge driver. Somehow my brothers and I were instilled with a sense of self-worth that would not be impacted or minimised by the limitations set by other people and institutions. We are not opposed to taking a longer or more difficult route ourselves and if that includes being isolated, we accept it. My younger brother is a screenwriter, and my older brother is an architect. I decided that I wanted to speak about these things because there were conversations I was having with myself which I felt were necessary to have with a wider audience. I was trying to make work about what it meant to be a person.

How does that conversation play out?

I was effectively told, “oh you mean a black person?. To which I went, “No, I mean a person.” I did not know that we had this distance. So, what you have been seeing is a set of cues and understandings which are limited by your take on what it means to be Black. That just made everything fall into place. I thought we had been talking as people, and they are seeing me as a trope. It made me realise that there are these veils, these different perceptions which we carry with us. I wanted to remove that. But you can only remove it if you get people to acknowledge it in some way. So it does drive me, but I don’t want it to define me.

Your exhibition, Matter of Place, just opened recently at Kunsthalle Krems.

Yes, I am currently showing a series of works there that explore what it means to become a part of a place and its physical material history. In addition, a large-scale sculpture of a young woman looking at her cell phone can be found in the public space, in front of the building.

Where do you hope to go next?

I’ve got lots of exciting projects coming up, most of which I can’t talk about. I never know what to expect, with showing works across a fair period to a new audience in different countries. I am really excited to see how the work is received. And I’m looking forward to creating more works, whether paintings or figurative sculptures, to keep pushing the works and their contexts, pushing the locations. I think that art practice is a continuous conversation with oneself.

Exhibition view, Thomas J Price. Matter of Place, 2024, © Kunstmeile Krems, Photo: Agnes Winkler

Exhibition view, Thomas J Price. Matter of Place, 2024, © Kunstmeile Krems, Photo: Agnes Winkler

Exhibition view, Thomas J Price. Matter of Place, 2024, © Kunstmeile Krems, Photo: Agnes Winkler

Exhibition view, Thomas J Price. Matter of Place, 2024, © Kunstmeile Krems, Photo: Agnes Winkler

Interview: Lillian Crawford

Photos: Liz Seabrook