Black mills, moonlight, empty landscapes, and geometric half-timbered houses: Titus Schade creates both mythical and minimalist visual worlds with his painting. His works are both surreal and gloomy, but also highly realistic.

Titus, were you already exposed to art as a child or a teenager?

The beginnings of my work go back a long way. I was born in Leipzig. My father studied at the Academy of Visual Arts, and my mother has been taking photographs since the seventies. That’s how I grew up in the art scene here and also with the pictures of the “Old Leipzig School” – these cityscapes, sometimes with figures, sometimes without people, brownish-beige in color. Moreover, as a child, you have no decision about which contexts you’re “thrown” into. I often went to openings for that reason. Then I began to paint myself. Every child paints to make sense of the world, so to speak. The blue stripe above was the sky, the green stripe below was the ground, and everything that took place in-between were at first everyday experiences. Unfortunately, many stop painting, some continue to do it as a hobby, and others, including myself, try to cultivate it further in their own way. Towards the end of school, I became interested in graffiti, design, and architecture.

And how did it proceed?

Later, I got involved with Bauhaus architecture. Between high school graduation and civilian service, I had a rather mixed time where I didn't really know where life would take me – but I was already focusing on painting and studying painting. I prepared a portfolio and simply applied along with friends to the Bauhaus in Dessau to study design. Despite passing the entrance exam, I found myself on on a waiting list as a result of the high number of applicants. To be on the safe side, I enrolled in architecture and studied for one semester. However, I realized that the practical was not for me and my desire to study painting solidified. With this desire in mind and in my heart, I applied to the Academy of Visual Arts (HGB) in my hometown of Leipzig with a more developed portfolio. It was at that time that I first came across Neo Rauch’s work, and I found the wide range of drawing and painting possibilities offered there very exciting. In 2004, I began my studies of painting and graphic arts at the HGB. After the first few weeks of basic studies, it was clear that I had arrived at what I wanted to do and that there would be no turning back!

And this was followed by master studies under Neo Rauch?

After two years of basic studies with classical figure drawing, still life studies, as well as graphic workshop courses, one applies to a professor of a specialized class for the pre-diploma examination. With many of my fellow students I applied for the class with Neo Rauch. In my case, the mostly rigorous consultations were often about the composition of the picture – whether one should move parts of the picture two centimeters to the right or left, for example. In order not to eliminate the parts I loved, I preferred to improve in my own way, the composition of subsequent paintings. In 2009, I passed my diploma exam. After that, I wanted to take my master student course with Neo Rauch and had to wait another two years for that – because of the number of previous diploma students. From 2011 to 2013 I was one of his few master students. In the meantime, the collaboration with the gallery EIGEN+ART was initiated. Judy Lybke had called me shortly before a master student exhibition opened here at the Kunsthalle der Sparkasse. That was exactly ten years ago. Amazing!

How do you look back on your artistic career in retrospect?

I consider the term “artistic career” a difficult one because it assumes so much. At the moment, I am not even 40 years old and thus, as it were, still at the beginning of my painting career. I also find the term “artist” strange. I see myself as a painter. Hearing the term “artist” I always think of high-wire artists or magicians. It somehow has something trivializing about it. I always say I am a painter. Painting is both a mental and a craft activity. And so is the process of how my paintings are created. I paint them in weeks of painstaking work, assembling different element. Often, I return to things I painted years ago, for example, and modify them. So, I am expanding my pictorial world. The term “painter” is simply more accurate!

And how long have you been here in this studio?

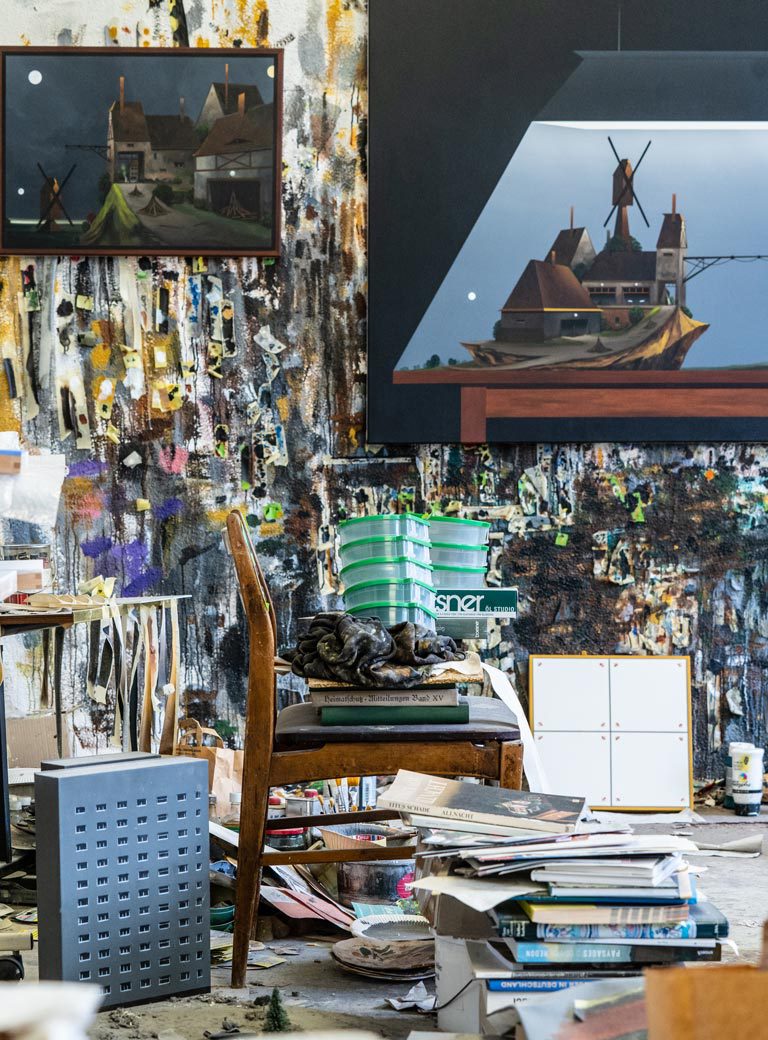

I have been here on the site of the Spinnerei since December 2012. When I was first here in this space, everything was white and empty – now it’s kind of a Francis Bacon cave. I should tidy up, but because of a busy exhibition schedule I can never get around to it. When you work with an internationally active gallery, there’s an expectation that you will contribute a certain amount of work connected with appointments and exhibitions that one naturally wishes to participate in anyway and you put pressure on yourself because you want to do so efficiently. The gallery is celebrating its 40th anniversary at the moment, so it’s older than I am. I am currently working on an exhibition that will be shown at the EIGEN+ART gallery under the title Die Schwarze Mühle (The Black Mill).

What will be on display there?

There will be about 30 paintings on display. If everything works out, I will also present a windmill sculpture there. But the focus is on painting, it’s like a game to me – a staging of things on canvas. Similar to a model builder who sits in the basement or attic in front of his plate, I create my own world. That’s how I see the painting process. That also is how I perceive the painting process. I populate landscapes on the canvas with buildings, vehicles, and with mountains and trees.

Titus Schade, Modelltisch - Bergdorf, 2023, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 120 x 170 cm, Courtesy Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin, Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin

Does architecture play an important role in your painting?

Architecture provides the viewer with the opportunity to be led into the picture. Regardless of whether it’s a building seen from a distance or a spatial situation that leads into the picture, such as a canopy – you quickly arrive at the core of the picture. And for me, a painting is always a kind of window, a door or porta into a parallel world. It is also very important to me in my painting to emphasize that it is a alternative universe, that is, a parallel world. My world functions according to its own rules, but in its representational nature it draws from our world.

Are your visual worlds inspired by the landscape around Leipzig?

Only partially. More often I paint mountains, for example. When I think of half-timbered houses, many people immediately think of southern Germany, but there are also half-timbered houses in the Netherlands, France, and England – even in Leipzig. When it comes to half-timbering, I am interested in the subdivision of the façade. I consider this constructing, even if it always requires an effort, more exciting than doing something freehand. And subdividing a façade like that is even more interesting. It has geometric and ornamental aspects that interest me from an architectural perspective.

How would you describe this interplay of construction and art, architecture and painting?

That I have thus worked out the possibilities of creating a pictorial contrast, i.e., things that appear as if printed or developed with graphics programs on the computer suddenly meet a classical landscape painting. First, I paint an impressionistic cloud and then, in addition, a mill, which seems to be built of steel, is brought sharply into the picture. It should be emphasized, however, that the things are all created directly on the canvas – without any preliminary work on the computer. Sometimes I capture these things beforehand on a drawing the size of the palm of one’s hand. On the canvas, however, the pictorial event then takes on a life of its own during painting.

When did you paint the first mill?

I remember that very well. In elementary school, I built a paper windmill. Even from today's perspective, it's not that badly made. At some point I found it again and painted it in the third year of study, around 2006/2007. And since 2015, it has appeared regularly on my canvases. I find mills interesting buildings, and in a purely symbolic sense they open a window into another world. They remind me of the Netherlands, of Flemish painting of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, which I appreciate very much.

How do you compose your pictures?

Most picture ideas circle around in my head long before they are actually executed. I often have an image in my mind's eye, and then I just have to execute it. I usually make a postcard-sized preliminary drawing where I list and arrange the individual elements – it’s like a little note. It only says roughly where something is to be placed. And then I put it on the canvas and, of course, see how it turns out in concrete terms, what distance the elements have from each other, for example. The preliminary work is always done in my head. The aesthetics of my works are strongly influenced by my childhood and youth, but also by video games or 3D rendering. But everything about the constructions is handmade and, as I said, I don’t do any preliminary work on the computer.

How long does it take you to compose in this way?

Difficult to say. Sometimes I only need a few days. For other work, I need several weeks or months. I work in a processual manner, painting for me necessitates a high degree of precision.

And how many stages does the painting process have for you?

Quite a few. For the table pictures that will be on display in the upcoming exhibition, for example, I made the tables piece by piece. This was followed by the lamps and the light cones above them. I prepared the tables a piece at a time, which means that one day I painted the canvases, the next day I applied a second coat, I then made the basic construction and filled the individual surfaces. It takes about two weeks, until I have four to five tables ready. So, I already have a framework on which everything takes place. Then I take each individual table and “fill” it with the picture objects one by one. I work consistently Monday through Friday and schedule for such predictable basic steps.

So, you spend a lot of time in your studio?

Sometimes I paint on several pictures at the same time. But if I am painting precise scenery, I only work on one picture at a time. I'm here from lunchtime on. Before that, I do some organizational work. Once in the studio, I often paint until late at night, sometimes even until five in the morning. Stopping is often harder for me than starting. First you arrive and you know the difficult parts are ahead of you, but once you’re in the working process, it’s hard to stop. It’s like being in a meditative state. I do things almost mechanically. I grab the ruler, cut the tape, grab the brushes and paint – all really as if in a rush. I work almost gesturally, perhaps like Hans Hartung or Jackson Pollock, but within a geometric framework. Just the other day I observed myself how the processes almost took on a life of their own deep in the night.

What role does the environment of the Spinnerei play for you?

A big role. For me personally, this “going to work” is very important. And of course, the Spinnerei site is important for the city as a cultural center. It’s like an open fortress or castle, a city within the city. Outside of the guided tours, it’s tranquil, and during the tours, people from Leipzig, other parts of Germany, and from all over the world come here to see painting and art. In addition, EIGEN+ART has its headquarters here. I’m close to the gallery and can handle things in an uncomplicated way.

How did the preparations for your exhibition with Andreas Mühe at Kunstraum Potsdam develop?

They went very well. The whole thing was very spontaneous.

Did you know each other beforehand?

We have known each other for more than ten years. And when we met, it was as intimate as if we had known each other forever. A crazy familiarity surrounds us, it’s almost as if we are like an old married couple. I had been given the opportunity to exhibit at the Kunstraum, and while I was calling Andreas to invite him to the exhibition that was to take place two weeks later, we got the idea while talking on the phone that we could do something together. We had always wanted to exhibit together. Within two weeks we set up the double exhibition. It worked out wonderfully, because the themes fit both of us, the basic noise of our works is similar, and our working methods harmonize.

Do you have any artistic role models?

There are always images from art history that circle in one’s head, that move me or have influenced me. For me, that would include Nighthawks by Edward Hopper, for example. This is such a fantastic painting that, despite its having been printed a little overly on T-shirts, mugs, and fridge magnets, loses nothing of its fascination! In terms of technique and precision, I appreciate Konrad Klapheck. I like Caravaggio’s use of light. I also like Charles Sheeler, an American Constructivist, who painted industrial architecture. My teacher Neo Rauch gave me the ability to paint everything that surrounds you and to put it into your own form and setting, to negotiate things in a timeless and universally valid parallel world. In doing so, you can open up your very own painterly cosmos, from the abstract to representational painting. Being able to paint anything requires a great openness, which I think is good. It also taught me to use painterly contrasts in one and the same painting. In other words, to pursue different painting styles within the same work.

Titus Schade, Die Fliese - Die Waldmühle, 2023, Oil and acrylic on wood, 25 x 30 cm, Courtesy Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin, Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin

What projects and exhibitions are you working on at the moment?

The next important exhibition opens on April 22 at EIGEN+ART in Leipzig. For this gallery presentation I have made many new works. Next year a big picture show opens at the Konschthal in Esch-sur-Azette in Luxembourg. The exhibition will probably start in January and go until May 2024, when I will have my 40th birthday. And otherwise, I am just preparing material from the last exhibitions. The presentation with Andreas Mühe in Potsdam was successful, as was my exhibition at the Kunstverein Augsburg last year. The catalog Schade, Mühe is currently being printed.

You travel abroad a lot. Do you miss Leipzig during such phases?

That is an important and frequently asked why I’m still in Leipzig. Many people come to Leipzig because they actually like it and think it’s great, and then they ask me if I want to leave! But I stay and am rooted here! My parents, my grandmother, my siblings and lastly most of my friends live here. I feel that I can only work in such a concentrated way in this place. I also like to go to other places, but I am always happy when I return to Leipzig and the Spinnerei. I would love to go to the Netherlands for two weeks, because the country inspires me. But I’m also not a person who takes more than two weeks of recreational vacation. Actually, I’m in the studio painting all the time. Sometimes maybe too much. But somehow, I need that ... Soon I will be 40 years old. People always say that something will occur in my work. Maybe I’ll even surprise myself. But in any event, I remain artistically and personally faithful to Leipzig.

Interview: Kevin Hanschke

Photos: Enrico Meyer