The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

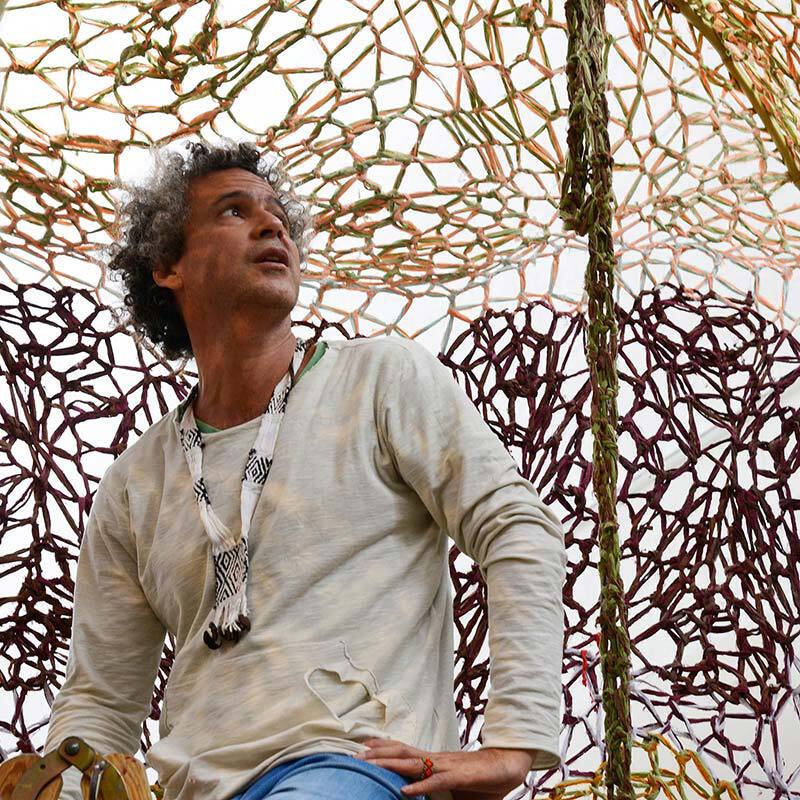

Visual artist Toni R. Toivonen examines the duality of life and reflects on the different sides of existence. Beginning with painting, Toivonen has worked with different techniques, including oil and charcoal on canvas, chalk on chalkboard and finally moving through experimentation toward a more conceptual outcome. Moving between abstraction and realism, Toivonen’s more recent golden-hued works on brass depict decaying animals lying recumbent. As the dead animal’s body decomposes and finally ceases to exist, it leaves its presence on a sheet of brass. The rotting process is physical and may be considered morbid or grotesque, but the trace seared into the brass surface creates an aesthetic image that is both peaceful and dignified.

Toni, we are out here in the Finnish countryside, in the middle of a forest. You were born in Helsinki, where you lived and studied. What led you to seek this solitude? And what does it say about you and your work?

There is one reason which is obvious when you are doing what I am mostly preoccupied with, which is working with rotting animals. It is something I couldn’t do within the city limits of Helsinki. When I started experimenting with processes of decay in the shared studio space of the Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki, I got angry text messages from my fellow students asking what those stinking boxes where all about. So I have to be here since I want to be free to be doing what I want. But also I want to be secluded and to isolate myself in order to be really close to the artistic process. I can always choose to go to New York or Helsinki, but I actually like being alone.

The area around the barn in which you are currently remodeling your studio is surrounded by tarped boxes which contain rotting animals. You chose to live just a stone's throw away from it. So your work is always around you… Doesn’t this feel depressing?

I don’t believe in dividing work and life. There is a self-portrait by van Gogh that is titled The Painter on His Way to Work. I don’t think that an artist can ever be “on his way to work.” An artist is always working. I want to keep my process close to me and I work as much as possible, often sixteen hours a day. It’s a lifestyle you choose. I cannot separate work from life.

What motivated you to study art in the first place?

I think I was driven by selfish reasons. It is my way of expressing myself and referring to some difficult personal stuff. It is my language, I found very early that I could draw well, while other people were good at other things. As I child I wished to be good at playing soccer, but I wasn’t. Looking back I think it was good for me as I was able to concentrate fully on drawing. I avoided fights at school and I made friends with bullies by drawing for them humans or animals killing each other. In a way, even then, drawing was and is still my currency.

Was there ever an alternative for you than to create art?

Actually there never was. I am from a very poor, working class background. My grandparents are from the part of Finland called Karelia, which at the time was part of Finland, but is now a part of Russia. They arrived penniless, and when my parents arrived in Helsinki, they too had nothing. There was an attitude in my family of work being a necessity, a means of survival, not something you would do for enjoyment. So I was pushed to apply my drawing skills towards a profession, for example graphic design or architecture. They never understood that being an artist is actually a profession as well. I always just wanted to draw and make art.

When and how did the idea develop to place a dead animal on a plate of brass?

It is a combination of many things. I was already working with brass and other different metals when I was studying. We had an open studio day and rather annoyingly some visitors touched the works leaving marks from the oils in their skin on the plate and I saw their presence permanently conserved. That was the beginning I suppose. A bit later, my wife was working elsewhere and I was living in the middle of the forest with my dog for a while. I slept all those lonely nights on a sheet of brass on which my own presence was retained. I showed this work in Helsinki and it received a lot of attention. After this I wanted to leave that “last” presence.

Why was it so important?

At the time, I was already doing okay with realistic painting, but I was looking to do something new, something that nobody has done before – initially a selfish reason.

What was the first animal you used for your work?

It was a raccoon dog. During one summer we were homeless and I was sleeping in my car and roaming about the countryside a lot, looking for road kill. On one of my trips I came across an abandoned dairy which is where I began experimenting with my first works.

Where do you get the animals you are using for your works today? Are they still using road kills?

At first they were, or animals that I found with my dog in the forest. But in my mind I had been thinking about working with a bigger animal, a horse for example. The first horse was really hard to get. I was contacting all kinds of people who have to do with horses, checking with horse farms, veterinarians, horse meat producers. I also had connections with hunters and people in the area who owned or worked with horses. They informed me when a horse died; some people would tell me they didn’t want their pets to become food or end up in animal disposal, they would prefer the idea of their presence being conserved.

What is your relationship to the animals you are using in your work?

I have met most of the animals when they were alive. I also use my own pets when one of them dies naturally, as was the case with the family cat. We have chickens downstairs, they are a rare completely black breed, even their meat, bones, and internal organs are black. They all have names and I am particularly fond of one rooster. When he dies, I will make a work of him.

What have been the largest animals you have worked with?

Cows and horses. A couple of weeks ago I found a dead cow about a 6-hour drive up north, in a pretty secluded part of Finland. A cow was too big to transport so I asked for permission to build a box on-site. I am driving there regularly to check on it and follow the degradation process. Most of the works in progress I am doing here, so I can be closer to them.

Can you explain how you go about it? You find a dead animal’s body. You place it on a brass sheet. What then?

That’s the idea in short. I’ve now been doing it for four years, sixteen hours a day so I’m aware of the many variables that can make a difference. I place the dead animal on a brass sheet in order to say something. I compose the work. It leaves a stain immediately. Over time, I have acquired a good understanding of how the decaying process of a specific animal will affect the outcome, of how salt, grease, and other fluids will make a chemical reaction with the brass plate. There are other factors too including temperature and humidity. I constantly have to monitor it. I check on the animals several times during their decomposition and decide when I will end it.

Does the process have a particular duration?

It depends. In the summer time it may take only 5 days. In the winter the period is longer, of course. And of course it depends on how dark I want the result to be on the plate.

You delegate the responsibility for the result to a large extent to a process. Does that make you a process artist, or how would you like your practice be discussed?

There is no single answer. I suppose you could discuss my practice in many contexts. You could say that I make reference to old school photography, because there are similarities with the gelatin silver printing process. You could call me a graphic artist, because in a way there is a printmaking process involved. Or you might say that I do sculpture, because it is a sculptural process in a way, and I am moving 600 kilos of rotting meat around. And in a way I am a painter, which I am by education. If pushed to give it a name I would call it conceptual painting or conceptual art, because the art involves the process. The Austrian painter Hermann Nitsch speaks about his paintings as a place of happening. I feel almost the same with regards to my own works. The artwork is a place of action. For each work there's a different act. The artwork – or what you see – is a relic of something that happened. And that ‘something’ that happened is art. The object you can buy is only a small fraction of the art that has taken place along the way.

Can you describe the artistic idea or concern that is pervasive in your practice?

One thing I am concerned with is the realism of the material. For example, the brass work you see here in the studio is not an image of a cow, it is the cow. The cow leaves its own liquids, salts, grease, and blood which leave stains and conserve the cow’s presence. For me that is important. Also it is a painting in a way. I used to be a painter, and studied painting. I believe in the reality of materials in painting. Another aspect is the duality of life that I believe in. You need to have shadows in order to understand the light. You need this balance. You need to see death to understand life in a way. I think the realism of the material and these questions of existence are connected.

Outside you have a stillborn calf lying in a box that has already started to rot. What would you tell someone who might consider your work cynical or macabre?

Most people who feel this way may be offended that I am actually making death visible. They are used to buying their fillets in the supermarket and have never seen an animal being slaughtered. Even if you live a vegan life one way or another we participate in animal deaths. But that is the way of life, sadly.

Are there any misunderstandings about your work that you repeatedly have to deal with?

I have to talk a lot about eating meat versus not eating meat, about animal rights issues and so on. Although I do have something to say about these subjects, that is not what my work is about. Another topic I am often confronted with is whether I kill animals for my practice. The answer is ‘No’. The animals I am using either died a natural death or they had to be put down because they were ill or suffering. Ultimately I want people to feel the art, not understand it, and that way raise new personal questions in their lives. I am interested in deeper questions that one cannot easily express in words.

Do you see any connection between your practice and that of Damien Hirst, who shocked the world in 1991 with The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, which featured a shark in formaldehyde?

Hirst comes up quite often when my work is discussed, as I am also preserving animals. But you need to get a little bit deeper than that. I have a book on my shelf called On the Way to Work by Gordon Burn in which Damien Hirst very openly talks about a wide range of topics related to his career as an artist. In it he also talks about the reality of the material. Hirst didn’t believe that material could persist in two-dimensional form, as in a painting. But I believe it can, in a way, as I just explained with the example of the cow print on the brass plate.

One of your earlier shows was titled The Aesthetics of Disappearance which seems to be describing your artistic concern very well.

This was the title of my very first show – actually my bachelor exhibition in Turku –, for which I made portraits from homeless people, painted quite expressively in oil. But you are right, the title still means something and can be applied to what I am doing. When speaking of aesthetics I think it also has to do with the duality of life that I was talking about. On the one hand you have a decomposing animal’s fluids, on the other hand you have that bright, shiny material. The result is quite beautiful and one almost feels a bit guilty for liking it.

If you had a say in how people interpret your practice what would you like to stir in people from viewing your works?

I don’t want to prescribe it. If I am reading a book I might choose to read it from the end to the beginning. It doesn’t matter. As long as I connect with one sentence in that book I don’t care about the story that the author has intended. All I can say is that I hope my work makes people think about their own life in a different way. Death can be beautiful. But that may be my very personal approach to the topic. Most of the time I am working with mammals, because I want people to sense that bodily quality implied in these paintings. I believe one relates to these works differently than when in front of an oil painting. One senses the mammal’s dead presence – with all its flesh, hair, skin, and fluids – and in doing so relates to one’s own body and its finite nature.

Your brass works have received a lot of acclaim to the point that they might overshadow the work in other media which you are pursuing in parallel. Do you want to talk to us about other aspects of your work?

I have one process that has been going on for two years now. It seems that now is the time to turn it into something bigger. For this new process I have been working with an ultra-sonic device, taking ultra-sonic images of the decaying animals at different times. I am trying to find beautiful landscapes inside their dead bodies. This looks like a cloud, but it is in fact showing the neck area of a horse, one week after the horse is dead. This one looks like a black sun above a horizon, it is the eye after one week of decay. I am then painting these ultra-sonic images in black and white with oil on aluminum plates. The images already work well on their own, so they may form another body of work themselves. The black-and-white character of these ultra-sonic landscapes is quite dramatic and reminds one of the style applied by 19th century Scandinavian landscape painters such as the Norwegian Peder Balke.

Although you have chosen an entirely new medium and are making new formal references, you are still concerned with the topics of life and death, or with finding beauty in death…

Yes, all my processes can be traced to the same source and are connected a lot. For example, for the ultra-sonic images I am using the same animal carcasses that I am using on the brass works. After decomposition, I clean the skulls and try to use remaining parts of the animal in as many ways as possible. Even after this, I am cleaning the skulls and try to re-use of the animals in as many ways as I can. This jar on the table containing what look like pickles actually contains horse testicles. I don’t know what to make with it yet, but it may eventually become part of a new work.

Does using the animal as much as possible also have to do with the respect you are paying for the animal?

I think there is a lot of respect for death involved in my work. You might think it is grotesque, but you could think of the opposite. What I am doing is to create a death mask of the animals, in a way. People may be shocked when they hear that, for some works, I may feel the need to cut off a dead animal’s head. But it has nothing to do with disrespect or cynicism.

What is on your mind for this year?

Above all I have to complete the attic of the barn. There are a lot of finishing touches to be made. It is hard to find the time for it though. Once it is finished, it will feel great to work up here. I never had such a spacious and bright atelier before. Then I am preparing my next exhibition which will be taking place at Galerie Forsblom in August where I will show my latest animal-brass-works, my largest so far, which will differ from previous works in their appeal. I might also show the new work-cycle of the ultra-sonic paintings relating to the idea of “beautiful landscapes inside dead bodies”.

Interview: Florian Langhammer

Photos: Florian Langhammer

Links: Toni R. Toivonen's website Galerie Forsblom, Helsinki