Through a combination of media, Tyler Mallison gives form to an ‘uncertain space’— characterised by traces of the ephemeral and actions that introduce the medium of time, body and movement. Across the work there is a marked emphasis on materiality, digital mediation and the expanded field of painting.

Tyler, how would you explain your work in only a few words to someone who doesn’t know you? What aspects do you work into your art practice?

Ah, the million pound question! I wish it were as simple as stating "I'm a painter", but my practice is rather ambitious and multi-disciplinary by its nature. It’s about ideas and engaging a combination of process-based material exploration and research — drawing on diverse areas of knowledge that span consumerism, philosophy, psychology, semiotics, science and digital technologies. Themes of desire, direction and dissonance are central — with a particular interest in actions that seek to incorporate the medium of time, body and movement. Across the work there is a marked emphasis on materiality, digital mediation and the expanded field of painting. That said, I try to avoid attempts to "explain" my work as it always leaves me feeling unsatisfied. Ambiguity has a place in art, unlike the commercial world.

When was that point in your life when you discovered the urge to create art?

Probably age 4. As soon as I discovered the basic skills to create images and objects, I became obsessed. I’m very happy to spend introspective hours on my own just experimenting and imagining. This was certainly the case when we met in San Francisco: A time when I was predominantly focused on painting and deepening my skills in photography and digital drawing. It was really during those years that I finally recognised I wouldn’t be satisfied without doing more with my art and "hyper-active" mind. I just didn’t know what that meant then or where that would lead me.

You started out studying chemistry/pre-medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, spending one year on exchange at Kings College London — both highly competitive academic environments. But something changed for you. What happened?

I became enchanted by the freedom and stimulation I experienced living within the diversity of Europe. I also began to realise that I could have a say in my life and its direction. After graduation, I therefore returned immediately and spent a further year exploring life in London, Venice and Perugia, before heading back to the US.

You ended up on the West Coast to begin life as a strategist or "planner". Why didn’t you take a route that brought you closer to doing more art?

At that time I was just figuring out how to make a life on my own and seeking new experiences. It was only by chance that I was introduced to what was then the emerging discipline of 'branding' and immediately saw something that ignited my curiosity and interest on a very basic, intuitive level: consumer desire and identity. I still self-identified as an artist, but it wasn’t yet something that I believed I had permission or resources to genuinely pursue.

You returned to the UK for your MA at the renowned Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design ten years ago, after which you continued to engage with branding and innovation, eventually setting up your own business. What was the ignition that finally let you take the step to spending more time on practicing art?

It was just a very strong feeling: Like pressure in an espresso maker that had built up over a long time and needed to be released. The decision to shift gears was difficult, but vital to make since I knew it was the only way forward.

Is there a process to becoming an artist—A critical point when you tell people: "You have known me as a strategist, but I am actually an artist?" How do you manage that perception shift in your social circles? It must feel a bit like a coming out…

You could say it is a "coming out" of sorts. It’s the product of a lot of self-analysis and heightened self-awareness. For me it was a very authentic statement to make, which coincidentally put me at ease.

We are here at London’s Westland Place Studios, a former tobacco pouch and smokers’ pipe factory in Hoxton, which is one of the oldest established artist communities in and around Old Street. When did you join and what do you appreciate about this place?

I moved into this studio community in June 2015, which has been a real gift for my practice. The building itself is very special. It’s a world onto itself in the midst of a vibrant, central area of London that is rapidly changing, day-by-day. I enjoy watching the incessant building work and skyscrapers going up all around.

Do you still take on strategic planning and design work these days?

The cost of space, production and living is incredibly high. Therefore being a London-based artist typically comes with a need to engage in other activities as well. I count myself fortunate to have an alter ego that allows me to explore topics of interest and travel regularly—continually developing new thinking and dialogues. This also helps to facilitate a sense of freedom in my practice, as I’m not forced to commoditise my artistic production.

How do you entertain the two aspects of what you do? Working within branding and the arts must feel like two different worlds, competing for your time, attention and of course different parts of your mind …

This is indeed very challenging, as it creates cognitive dissonance at times. But I’m quite interested in this psychological tension in itself. I therefore try to use this mental space in a constructive way within my work.

What does it mean today to be an artist?

As with everything, there is multiplicity inherent in the answer. For me, being an artist means being curious, asking questions and keeping committed to an individual journey of exploration and discovery—giving form to an uncertain space that’s informed in part by the personal experience.

Has the art world changed over recent years?

The biggest change is the visibility and economic value of the art world. Around the artist has evolved a highly sophisticated international art market with an estimated worth of nearly €50B (2014). Most of this value is associated with a small set of artists and galleries relative to total production. Therefore, finding support and opportunities as an emerging artist is a challenge. The digital space has emerged as a democratising agent in this system to some extent, providing a platform for sharing and producing virtual work. This is something I have also been exploring in my projects.

You use a wide a range of materials and mixed media in your work, including photography, textiles, pigments and digital technologies. How did the choice of media evolve over time?

I choose materials for their ability to communicate in the context of the work. This could be anything from the qualities inherent in the material/object, relationship to the body, semiotic associations, or a motivation that’s less evident. My use of ready-made clothing as a medium grew out of a growing interest in materiality and its ability to serve as a proxy or analogue for themes of identity, personal curation and display. On a somewhat formal level, it also seemed a natural medium to work within the expanded field of painting and in opposition to the digital, controlled and systematic.

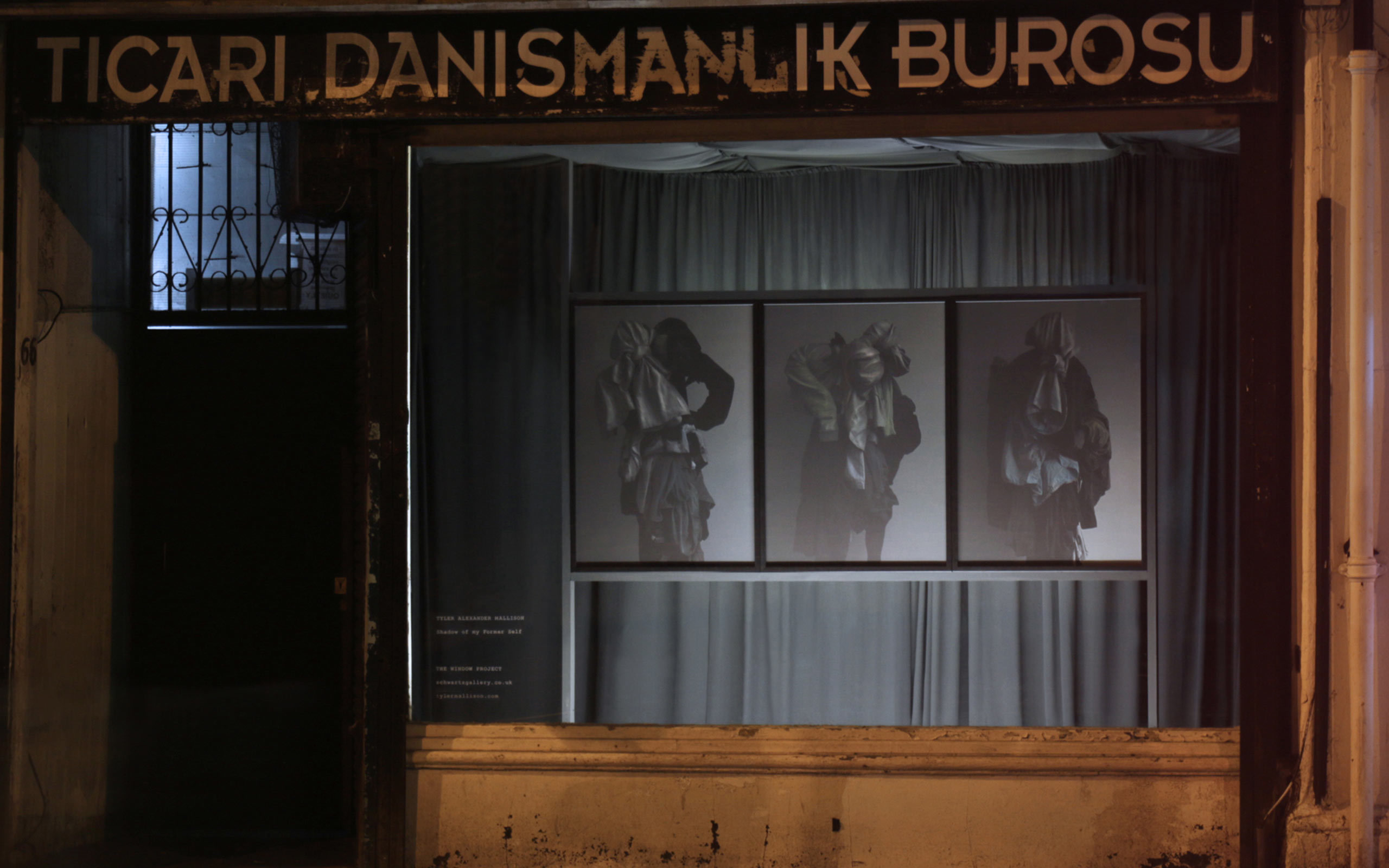

I was personally impressed by the Shadow of my Former Self series (2013), which captures a sense of ambiguity and perhaps melancholy. It comprises large photographic pigment prints, video and animated gifs accessed by the viewer through their own smartphone or tablet. What thoughts did you work into this series?

The project was very personal and intuitive, wherein I decided to work with the medium of clothing removed from my own wardrobe in conjunction with my body. I had been interested since Project Wardrobe (2005) in what these highly personal objects signaled— identity, choice, consumerism, image manipulation—and I wanted to explore what would happen if this outer skin were shed, effectively marking the death of the former self. People often comment on this work and I wonder whether it connects with viewers on some subconscious, primal level. The work itself is a dynamic meditative process wherein both the being and object are in a constant state of flux. What interests me greatly is the almost classic quality that emerges within the compositions, reminiscent of a formal portrait or still life setting, but which is in fact the product of a spontaneous and fleeting action.

Another work I am drawn to is Accidental Sushi (2014). Can you tell me a bit about what led you to produce giant stuffed toy-like sushi rolls?

Well, I can assure you that I had no intention to make 'giant sushi' when I initiated the project. (laughs) Accidental Sushi is in essence a reflection on contemporary culture, inspired by a bus experience on the M29 in Berlin with Norwegian/German artist Yngve Holen (Ars Viva winner 2014-15) during a short residency with Autocenter Contemporary Art Berlin. The work takes the mundane and 'everyday' as its starting point, embodied by the humble sandwich, and marks our fetish for the exotic. The title plays on the word 'occidental' and references both the journey from east to west and an inside-joke about the accident experienced en route: There were ambulances, fire fighters and everything. It’s a good example of how diverse media and found materials play into my thinking—including ready-made embroidered carrier bags, work gloves, foam, household sponges, microfiber, paper, a woven beach mat and brick, compact fluorescent light bulb, printed text on paper and of course fresh loaves of sliced bread!

Clearly clothes and loose material play a key role in your work, more recently in works such as Prime Arcadia, which you exhibited at The Engine Room at AWOL Studios Gallery & Project Space in Manchester. What is it about cloth that fascinates you?

It’s a combination of the raw materiality and agency such materials provide. I’m drawn to inherent physical traits, such as colour, texture, surface and form that are ‘real’ and manufactured by complex industrial and marketing systems rather than the artist. Prime Arcadia was a deliberate progression away from used clothing that carried a personal history, towards an open system of untapped possibilities and potential embodied in the 'new' textile object available in every size, shape and colour. I chose basic 'throwaway' T-shirts from Primark – the play on words shows in the work title – since they represent the least-common denominator in manufactured clothing and have become notorious for the myriad colours available. Each seasonal pantone-determined shirt becomes a new colour in my own painting palette. They are also only £2 each and produced in Asia, which introduces a further subtext of interest on value, globalism, movement and migration.

Wooden pallets are another recognisable material in your work…

That’s right. They are another ubiquitous constructivist agent that has almost nil value and sit overlooked on just about every corner. They also help materialise this nearly invisible web of global movement and limitless permutations. Through the act of pulling these items out of their respective systems, they lose their ability to serve an intended function and confront the viewer with new questions.

You seem to prefer installation over "wall art". If your art can be hung it often corresponds with elements in the room. Is that a valid impression?

To some extent, yes. I tend to think in terms of projects and bodies of work that have many facets. As such, different components give shape to an idea. For me it’s therefore important how these art objects inter-relate to make the whole viewer experience. That said, individual works within this framework can be extracted and stand on their own. But the initial presentation and context continues to play a key role for me.

Due to their dimensions and installation character, many of your works may be hard to collect, unless you are a major collector with a dedicated exhibition space. Is that consideration important to you at all in your work?

No, I don’t think about such limitations when conceiving work — if anything, I tend to scale-down my vision due to self-imposed practical limitations of space and storage. I watched a documentary on Anselm Kiefer last year and admired the scale of his working space. To have a large factory or warehouse to store materials and stage works would be a dream for me. My ambition is to take on larger scale projects, so I’m therefore keen to forge new relationships with like-minded curators, collectors and institutions that have a mutual interest in development and installation of such work. Any suggestions? (laughs)

Who collects your work?

To date most works have been staged in project and artist-run spaces, where there hasn’t been a focus on selling. Therefore, my collector base is small at the moment, with select pieces in private collections within Europe and the US.

What do you think it is that drives people to collect art?

I would hope it’s because the collector finds an art practice or particular piece of work engaging and thought provoking: Something that they feel is relevant or perhaps significant to the discourse they follow or curate through their own collection.

Are you fascinated by collecting yourself? What do you collect?

I’m definitely a collector by nature and have many different types of collections. There are physical objects — mid-century furniture, decorative modern ceramics, clothing, rocks, wooden pallets — but also printed material such as illustrations, branding, photographic imagery. The list is always expanding, as I often start new collections as I’m developing an idea. Again, the main limitation seems to be space.

You had a very busy year in 2015 with quite a few exciting shows — which one stands out for you?

Summerville in Wilmersdorf was a stunning exhibition in Berlin, hosted in a large vacant 1920’s flat by a great group of artists. I was invited to take part after a chance meeting with the artist Michaela Zimmer, who is represented by Fold Gallery in London. It was just ‘one of those things’ that started off as a casual conversation at a Berlin opening and quickly led to seeing shared interests in our practices and an appreciation of one another’s work. I chose to show a 'virtual' piece that I had been wanting to stage for some time — the .gif series of Shadow of My Former Self — along with a new series of monochrome prints on A4 paper. I was particularly satisfied with the context the show provided the work, given its equally transient and ephemeral nature.

What are you working on right now?

As per usual, I have a number of ongoing projects that are in parallel development. One project in particular is Arcadian Algorithms, which is multi-media with a large component of painting. Therefore, I’m spending quite a bit of time these days painting in the studio. I’m also completing the renovation and reorganisation of my studio, which is no small task. But my working space is incredibly important to me, so it’s a highly worthwhile investment of time and energy.

Are there any upcoming shows featuring your work?

I just finished Artworks Open in London, which is curated annually by guest artists through the Barbican Arts Group Trust, along with Show What You Want Show 2 in Amsterdam at the Melkweg. This coincided with a feature of Progression from my wider project Prime Arcadia in the Dutch art magazine Platform Platvorm. It’s been a very busy end of the year! I’m now turning my attention to the planning of future shows in the year ahead. Stay tuned…

Links: