Yingmei Duan originally trained as a petroleum engineer before moving to Beijing to pursue her artistic dreams. After a few years of studying painting and drawing, she became part of the renowned East Village collective, where she became enamoured with performance and co-created To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain (1995), one of the classic performances of Chinese contemporary art. Since then, Duan has moved to Germany, studied under Marina Abramović, and worked with everyone from children to retirees, scientists to philosophers. She’s created hundreds of works in the process – so many that she rarely shows the same piece twice, and even changes what’s on show during her exhibitions.

Yingmei, how did you first become interested in art?

Since I was a very young child, I’ve had a problem with speaking, I found it frightening and barely spoke until I was 21 years old. If you don’t speak very much, you must find alternative ways of communicating with the world. For me that was drawing.

When did you realise that you wanted to pursue art professionally?

I was born in 1969, and my childhood coincided with the end of the cultural revolution in China. People were still living very simply. Even though it was my dream to learn about art and drawing, I didn’t really know where I could do that. I just drew by myself and didn’t learn anything from anyone else other than my brother.

As a result, you initially trained as a petroleum engineer at Northeast Petroleum University in Daqing.

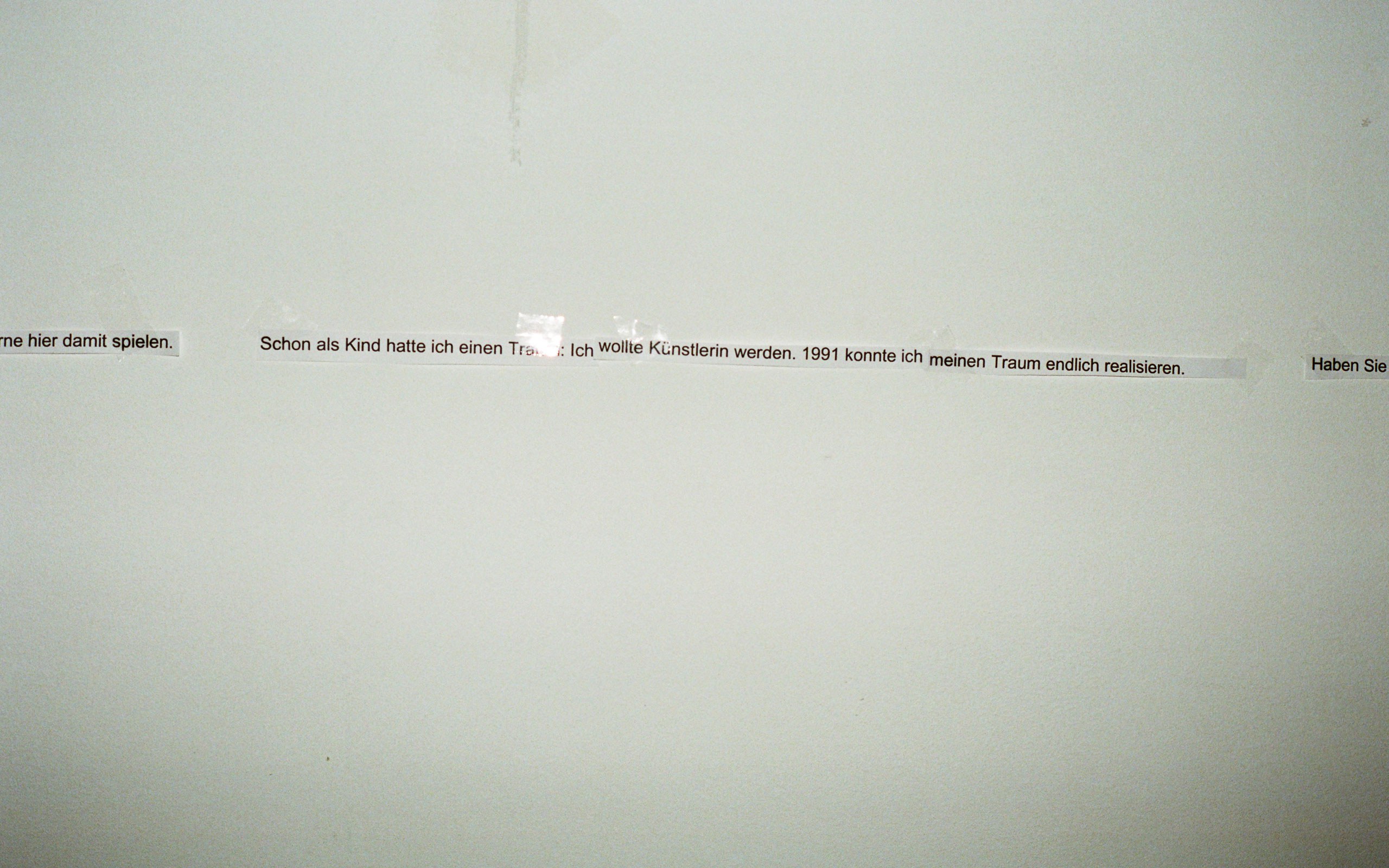

I wanted to study medicine, but it was very difficult. I studied petroleum instead because my hometown was a petroleum city. After graduating I worked in the industry for one year, but I always struggled with speaking to people, which was an important part of the job. In 1991, when I was 21 years old, I had a major operation in Beijing to help me with enunciation. This changed my life. After the operation, I had nine days off to recover, and for three days straight I dreamt about art. I told my father about it, who looked for a private art teacher for me in Beijing. He found someone from the Central Art Academy, so I stayed in the city to study art.

What did you learn from that teacher?

He told me that really, I was too old to start learning drawing and should go back to engineering. He believed to become an artist you needed to start training at a very young age. Nevertheless, he accepted me, and he was a very good teacher. I learnt quite quickly – after only a few months I could do a good drawing of a human head. I think my experience with mathematics helped a lot. Every day that I learnt to draw I was happy. I was living my dream – a feeling I continue to have to this day. I just want to create, always.

How did your training progress after that?

After a few months of drawing objects, my teacher told me that I should create a drawing or painting from my imagination. I was quite nervous about this and wanted him to choose a subject for me instead. “No. If you had to do a test at the academy, I wouldn’t be there to do it for you,” he said, offering me indirect encouragement. This was quite unusual – normally art students in China must do still life and life drawings for many years, and don’t start creating their own compositions until the end of their studies. Shortly after, I enrolled to do an advanced training course at the Central Academy. It was tailored towards people who had studied art as a hobby for a very long time alongside their day jobs in factories or schools. I was quite young in comparison – studying with them made me grow up a lot.

A few years later, you moved to Dashanzhuang village in Beijing, a legendary art district that was home to the Beijing East Village collective, of which you became a part.

I arrived there in the summer of 1992 by accident. In the beginning, it wasn’t even called the East Village, and there were only a few artists there. By 1993, more and more had come, and there was a group of about ten of us. We all used to gather together to discuss art and our careers. I was quite naive though, and less outgoing than the others, I mostly listened. as others. I mostly listened. We used to listen to a lot of music together too. There was this musician, Zuoxiao Zuzhou, who sold cassettes of American music from the sixties and seventies in the streets. Most people in China hadn’t heard this kind of music in the early nineties. It was illegal to own these cassettes, which came through Hong Kong. Zhang Huan, one of the key members of our group, met Zuoxiao Zuzhou one day and invited him to come and live in the village. Later, Zuoxiao and I lived together. We listened to rock and roll music together every day for many years. My favourite bands were The Doors, Nirvana, and Queen.

How did the East Village become more interested in performance art?

It happened overtime. Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, Zhu Ming, and Cang Xin were especially interested in it. I found what they did so interesting, something about it really touched me. I was very shy, but I felt compelled to take part. After painting and drawing for so many years, I knew I needed to experience something new. Many of the non-artists living in the village had a problem with our performances though. For example, for one performance, Zhang Huan walked naked from his home all the way to a public toilet. The villagers didn’t like that. They reported us several times to the police.

One of the most famous pieces the East Village performed was To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain (1995), which has become one of the classics of Chinese contemporary art. You were part of it. Can you tell us about that experience?

We invited journalists, writers, videographers, and a photographer. The day after, there were news reports about the performance both in China and abroad. There were not so many reports about Nine Holes though, another performance we did on the same day. At that time the East Village wasn’t as famous as it is today. The contemporary art scene started to develop more in China around 2003. Since then, we’ve become more known, and the East Village is regarded as very important in discussions concerning Chinese contemporary art.

There were ten performers/co-creators in the piece. Were there any challenges that came along with working collaboratively in such a large group?

In 1999, Zhang Huan applied to the Venice Biennale To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain, claiming that it was his work. Around that time, I got a fax from Ma Liuming asking me to add my signature to a letter stating that the work was a collaborative creation between all the artists involved. Everyone was very upset, because we had all paid for the materials and cassettes that we used as part of the original version. It was our collective work. I can’t remember who had the initial idea for it. Zhang Huan says it was his, other people say otherwise. To me, it isn’t important. I’ve done over 100 collaborative performance projects in my career, sometimes with over thirty or forty people. When I decide to work collaboratively, I view even the ideas that I put forward as joint – I wouldn’t have come up with them if I hadn't been in a creative process with my collaborators. The work belongs to us all, we all have equal copyright. I prefer working like this because it’s simple. I’m not interested in who has copyright and who doesn’t, I’m interested in how an artwork develops. This approach applies whether I’m working with artists or non-artists. I work with people from many different areas of society, from retirees to children, scientists, professors, and philosophers. I’m interested in humans, and what people do. I like everything. Every discipline is interesting, not just art.

In 2000 you moved to Germany to study fine art at the Braunschweig University of Art. What attracted you to this school, and Germany in general?

After 1995, we were no longer allowed to live in the East Village, so I moved to what is now the Songzhuang Art District. I lived there for a few years but wasn't happy and wanted to change my life, so I learned German and applied to study at an art university in Germany. I’d been to Germany before that. Hans van Dijk, the founder of the New Amsterdam Arts Centre in Beijing, and Detlef Pilz from the East German Ministry of Culture visited me in the East Village in 1994. Detlef was preparing to curate a large Asian art exhibition in Germany. When he saw my paintings, he was very excited and invited me to put on a solo exhibition there. Six months later, I went to Germany for the exhibition and stayed in Erfurt for a month. I was the first East Village artist to go to Europe.

During your course, you met Marina Abramović, right?

I was still shy about performing in front of people, so I made performances for video instead. Marina watched a few of them and accepted me into her class. She knew that I was very studious, and always working hard. One day she asked me to show the class what I’d be doing. I shared a full studio of works: paintings, sculptures, metalwork, woodwork, prints and so on. Marina told me that she felt my presentation was that of an academic student, rather than of an artist. None of the other students complimented me on my work either. I was very sad, and a little angry. I knew I was better than them – I was very diligent, and they weren’t. I criticised myself too. I realised that I’d done too much. That was the day I decided to only focus on performance.

What was Marina’s teaching style like?

She was a very good teacher. Her teaching was not limited to the university’s campus. She loved to take her students to perform in museums, festivals, and other platforms around the world, for example at the Venice Biennale and the Van Gogh Museum. We were so lucky because other professors weren’t so generous. I had a really beautiful time at the university because of her. She changed my life.

I love computers, 2005, performance, Photo: Stefan Simonsen

Corner, 2002, performance, Photo: Silvia Garcia

You exhibited art professionally while studying and showed your first “changing exhibition”—exhibitions in which you alter what is displayed, or how it’s displayed each day— at OKS Gallery in Braunschweig in 2003. What inspired this format?

There were many things. Sometimes I go to exhibitions, and I see that the work on show there is the same for three months. When I look at it, I think of the hundreds of different possibilities for how it could be displayed. I like to show different possibilities. If I have a one-month exhibition, I always change things during that time if it’s possible. It allows you to think a lot, develop things, work with the space, and to train your intelligence.

After stripping back to just focusing on performance, you’ve reintegrated paintings, videos, and other mediums into your practice. For example, you’ve started exploring music and singing more deeply, releasing your first album, Forty-Eight Years Ago, the Road an Ocean’, in 2018. What prompted you to take this direction?

I’ve worked with sound and music in my performances a few times before – sometimes I’ve sung improvised melodies during them. Maybe this is because of Zuoxiao Zuzhou, my musician ex-boyfriend. I sang on one of his albums. He gave me a lot of encouragement.

Nine holes, 1995, East village artist, performance, Photo: Lü Nan

To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain, 1995, East village artists, performance, Photo: Lü Nan

How else would you say your approach to your artistic practice has changed over the course of your career?

With time I’ve gotten better and better at speaking in front of audiences. Now, I can speak to up to 100 people, in any space, in any country – I’ve visited over 40 countries for exhibitions and residencies – and I don’t have any problems. I owe a lot of that to Marina; during my time in her class, I got used to dealing with situations that made me uncomfortable. I’ve also gotten more and more interested in working with audience interaction and collaborations. Interaction and collaboration open up the possibility of your performance going in a different direction than planned. I’ve gained a lot from working on interactive and collaborative performance projects. Over the past 23 years I’ve always been making, doing, and experimenting. Doing is an artist's job. I know some artists who are always visiting other people’s shows to get inspiration, but I don't feel the need to. I can write 20 different performance concepts in two days, and I always create new works for shows rather than exhibiting the same piece many times. If you always work, you are always generating ideas.

What are your ambitions for the future?

I would like to do a solo show at the Tate Modern. I’m very confident that this will happen. I’m going to keep doing, thinking, developing at my own speed, not worrying about what other people are doing around me.

Interview: Emily May

Photos: Sabrina Weniger

Links: