Through his installations, sculptures, videos and photographs Andreas Fogarasi is concerned with the act of showing and of representation. He analyses how places, cities, political ideas, or historic events become images and questions the role of culture – art, architecture, and design – in this process. Underlying his works is his critical examination of the mechanisms with which political appropriation operates in the field of visual culture today. We met him in his Vienna studio and asked him how it feels to become so famous at a very early age and what the surfaces of a city reveal about the people who live in it.

Andreas, can you still remember when you first thought “I want to be an artist?”

Actually, I always wanted to be an artist. By the age of 14 or 15 it was a fairly clear goal for the future, not because I was so incredibly good at drawing, or because I was a classically gifted child who was recommended by art teachers to attend art school, in fact I could never actually draw very well, and I always wanted to make conceptual art, but architecture and design were also options at that time. To become an artist, I thought, I don’t have to study art, however, if I want to become an architect I do have to study architecture. That’s how I came to study architecture. In my imagination, architecture was open to other disciplines, however, it was not exactly how I imagined it to be and it soon became clear that art and architecture would remain two very different worlds between which I would go back and forth.

To stay with this subject: after studying architecture, did you go on to study art?

Exactly. Before and during my study of architecture I always thought artistically and developed projects, had ideas, and created things. When I finally decided to terminate my architectural studies it was just before the finals to obtain my diploma.

Well, that was quite brave. How did you feel about it?

I felt so good! That decision caused an enormous burden to be lifted from me. I had never really got into architecture, although it has remained a very important subject for me. But the practice of architecture and the self-confidence of the architect was not a good fit with me. At the same time, I had already been doing my own artistic work, had had my first solo exhibition in a Belgian gallery in 1999, when I was still an architecture student. So it was a relatively smooth and natural transition. I then attended Renée Green’s class at the Vienna Art Academy and completed my study with a diploma in the fine arts. I still had that much bourgeois aspiration. (laughs)

You are addressing it right now with your first solo exhibition; you have become successful very young. How did it happen so fast so early?

I think the main reason was that I got involved with the art world very early on. I knew what a gallery is, what institutions and curators did. There were a lot of art students who after the completion of their studies asked: “Oh, and now what?” I think it’s different today. But back then, one didn’t really come into contact with the art world during one’s studies. But I had tried to understand this world long before my studies trying to get in touch with people who interested me.

So you were actively networking?

Exactly, I also attended a lot of exhibition openings, and I remember a very early meeting with Hans Ulrich Obrist, when I was 17. Someone said: “Ah, you’re interested in art? Why don’t you meet Obrist? He also started very young. And then I met him, not with the intention of “now I am contacting an important curator as a young artist,” but simply as someone involved with art. He was someone who wasn’t that much older, but was right in the middle of the art world. I found that exciting.

In retrospect, what was your first big and important project?

My first important international exhibition was the Manifesta 4, 2002 in Frankfurt; that was even before my graduation. It was a really big step for me, in the professionalization of the work and of course in the perception, here in Vienna and elsewhere. It was suddenly easier to make connections, to have an international business card, so to speak.

How did it happen that you, a Viennese artist, represented Hungary on the 52nd Venice Biennale?

Hungary announced an open competition from which to select a concept for their pavilion. The curator Katalin Timár, with whom I had already done one or two smaller shows, developed a project. At first, I would have played only a part in it, but eventually I proposed my Culture and Leisure project, which was accepted.

What is Culture and Leisure about?

The project is about houses of culture in Budapest, a system of institutions very much linked to modernity. I have researched the history of these places, which go back to the labor movement and were built in large numbers under Socialism to bring culture to the masses. I visited these places, filmed the buildings, and conducted interviews. In total, I made six short films about six of these buildings, each of them a few minutes long, they are documentary essays, which were presented in a sculptural installation consisting of six projection cubes in the pavilion. I was interested in a broad spectrum of different discourses, including an architectural one. Often you don’t see in the films what actually happens in the houses in day to day life. You see the foyers and the halls, how the buildings are positioned within the city, and therefore how they relate to the urban context. My research and the interviews conducted appear as a narrative in the films that describe both a specific story and an associative reflection on the role culture plays in the city and in society today, and who decides on that. This complexity created a difficulty for some critics, especially in Hungary where the embedding of the topics in the context of an international discourse on modernity was not always fully appreciated, and we received some very bad newspaper reviews.

You were born and raised in Vienna, but your family is originally from Hungary. Against this background, was it very special for you to exhibit in the Hungarian pavilion?

In the context of the Biennale, I particularly liked the fact that it called into question this annoying concept of national representation, in passing, as it were. I represented a country whose citizenship I don’t have, but with which I have a lot in common. I believe that my partial or incomplete Austrian identity has allowed me to do a lot in Vienna, for example not to be involved in something so completely as to lose sight of any objectivity. I certainly would not have received the Austrian pavilion at that time. This alone – who I was and how I came to be here – is not a matter of course and indicates the complexities within Europe and its history, political events, tensions, and contexts.

Is the examination of history in various facets the core of your artistic practice?

I believe that I look at how cultural phenomena or artifacts, some of which originate in the past, have certain effects in society. I am interested in the interactions, and architecture is one good example where both political and financial power and creativity meet permanently and to a particularly large extent. For that reason architecture is often a particularly good vehicle for me to reflect these questions. However, it is not architecture “in itself” that interests me. My work is about urban transformation processes and cultural production and how it is used: as a location factor, for example, by politicians, city marketing, and so on. Just as Louise Lawler is interested in what happens to works of art that become commodities depending on the environment they enter, so I look at architecture, design, and typography. I’m interested in how these find their contexts and how they are both placed and perverted in the world. This is an important reference for me. This determines how I look at architecture, also in my photographic work.

One of your current works has the title Envelop. How does this series fit in this context of urban transformation processes we have just been talking about?

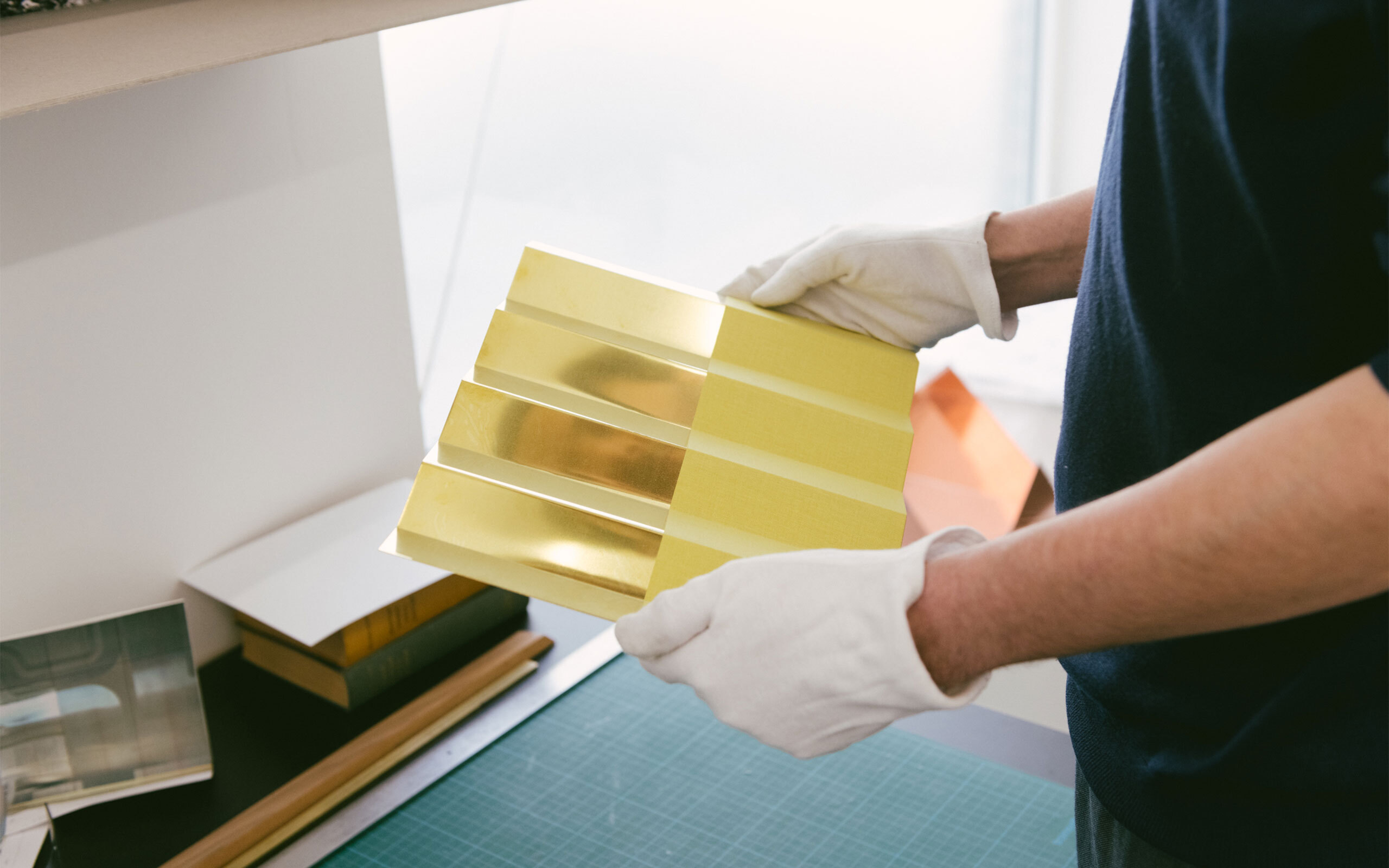

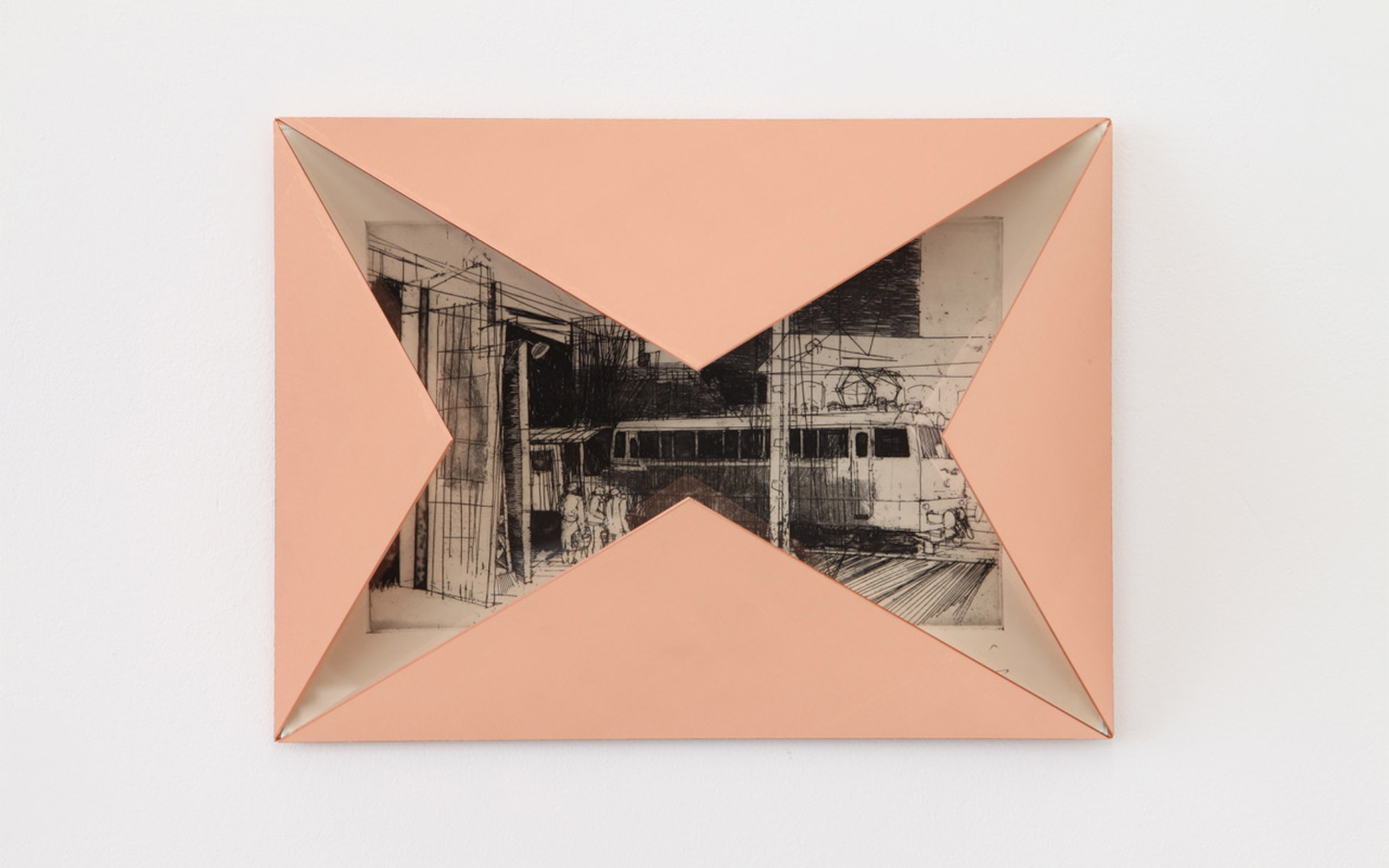

Some time ago, I began collecting copperplate engravings, again in Hungary, many of which had been made in the 1960s as public commissions, even though they occasionally contain avant-garde imagery. For many artists, this was a way to earn money. They were commissioned by the state gallery system to process certain pictorial contents. The artists were sent to factories, for example as in the former GDR, and in some instances they were able to work with the technologies of the respective companies. In recent years, I have repeatedly bought copperplate engravings of this kind, which deal with construction or infrastructure projects and which show, for example, construction sites, marshaling yards, bus garages, telecommunication towers, and telephone exchanges.

The starting point for this was that the artist János Major, who had already played a central role in my work Vasarely Go Home was an excellent engraver who had earned his living with this craft for many years. I bought my first portfolio because it contained one of his works as well as one by Dóra Maurer, who is known for her conceptual photographic work and geometric abstraction, but who was also a master of engraving and wrote a book about it. In addition to her freelance work she had made these commissioned works. By buying a portfolio you acquire many other works from the time, and many of them are very beautiful and have different qualities in the picture design. And you notice that it is often about something completely different from what is depicted in the picture, as we know from the discourse on painting. And then the desire arose to exhibit these works, to show them and create frames for them. Then I made these cases, these frames for them, objects folded from copper plates, showing these works. When you get very close, you see them very well, but when you look at them from a distance, certain parts become hidden. Shiny metallic stars that apostrophize presentation and (self) censorship in equal measure. Showing and hiding, packaging and framing that is actually an important constant in my work.

What does your artistic work tell us about the society we live in?

I am interested in what happened in the society I am investigating at the time. That’s practically the next layer to which my work still refers. It is very important to me to identify everything precisely. Often certain times or dates are linked to historical knowledge or personal memories. Researching these associations and memories a little further is intended as a stimulus in my work. This is perhaps not such a surprising insight, but many aesthetic decisions are very much anchored in specific times. The fact that in the seventies a lot of things were brown or orange and there were mirrored panes is one example. Now you can think about why that was so important back then. But it can also inspire us to think about the fact that the materials and color spectra that surround us today are also strongly rooted in our time. Today, everything is so in “shades of grey” and in ten or twenty years’ time we might look at it and find it very strange that color is missing and that materiality is just the way it is. I am interested in the time-bound nature of cultural production.

What are you working on now, what are your plans for the future?

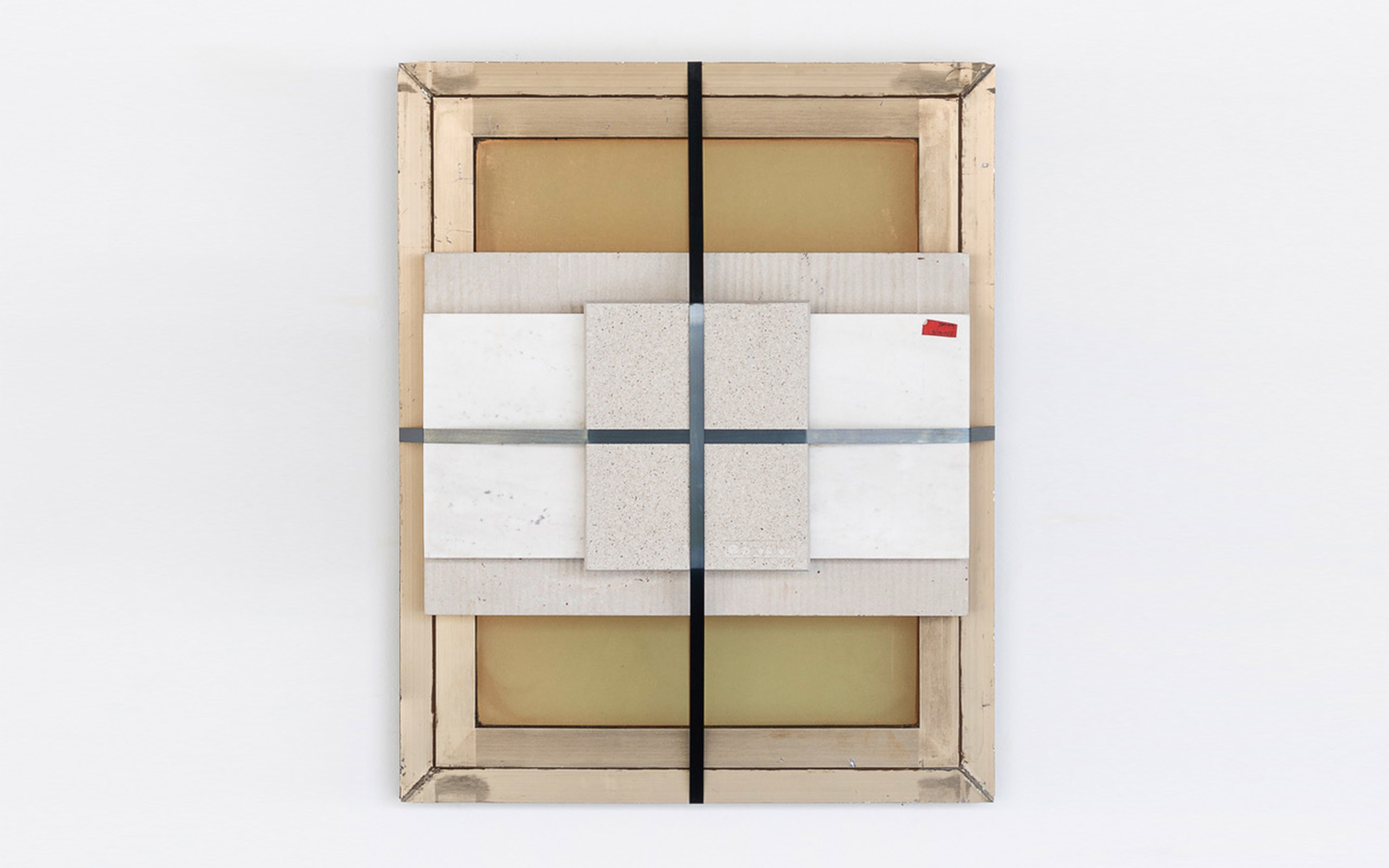

On the one hand, the project Nine Buildings, Stripped that I showed at Kunsthalle Wien, is far from being complete. I have been observing Vienna, the city in which I live, for a certain period of time. What changes are happening in the cityscape? I collect parts of buildings that are torn down or deconstructed and which are given a new façade, both parts of the old that is taken away and parts of the new that is built there instead. I make sculptural before-and-after portraits of these parts by piling up pieces of the building’s façade, floor tiles, tiles, etc. like a stack that hangs mounted to the wall. Some of the buildings that I have begun to work on are still standing, like the InterContinental, a project that has been subject to public controversy.

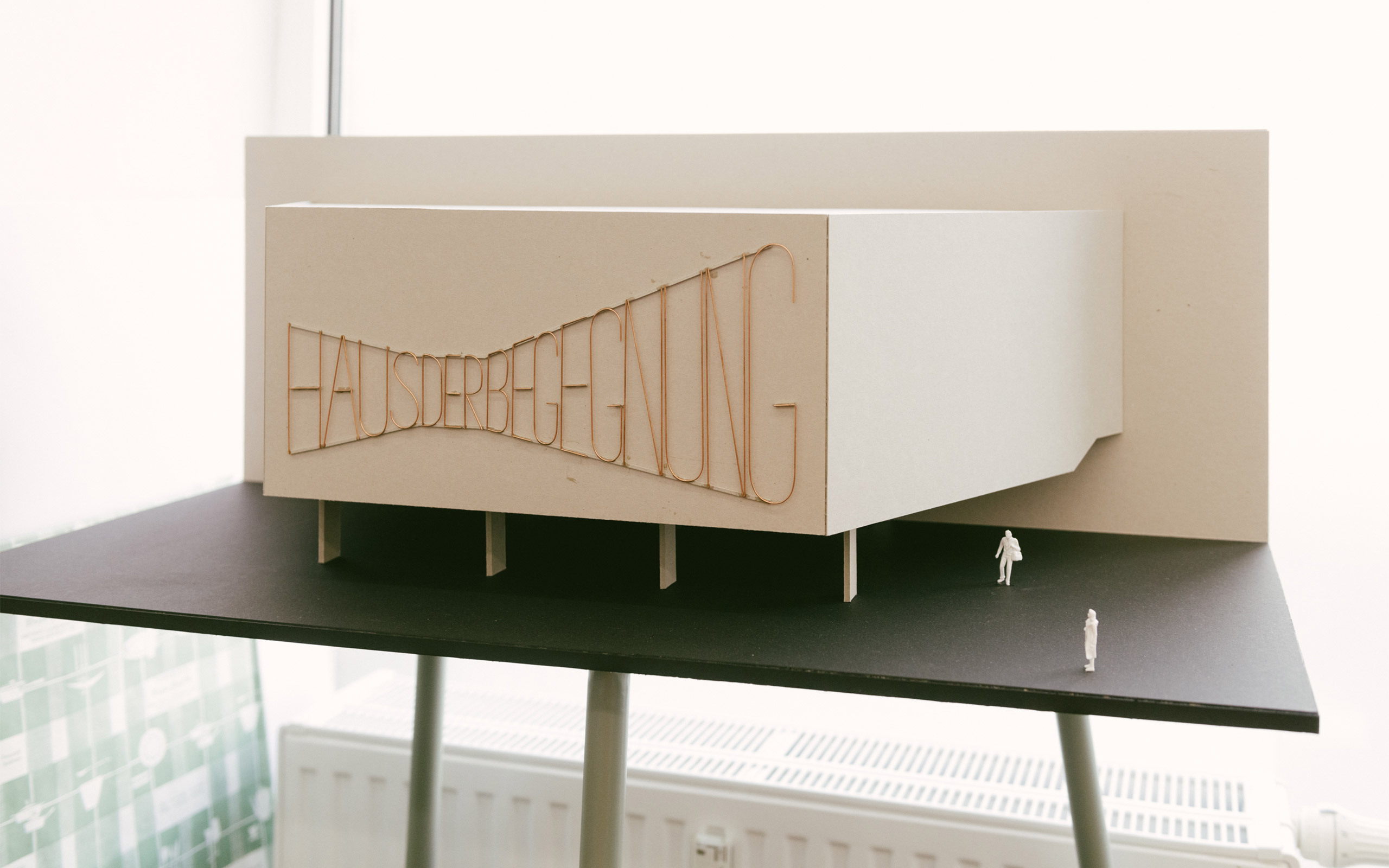

Another project, which also deals with a façade, is soon to be completed, in the Per Albin Hansson settlement in Vienna. I will write “Haus der Begegnung” on the large event hall, which used to be called “Haus der Begegnung” and is no longer so. It is located in an enormous apartment block from the seventies designed by the architect Carl Auböck. I have designed a perspective distortion that is evocative of sixties typography, but with luminous, shining LED lettering. I really like “Haus der Begegnung” as a word picture. It’s clear what it could be, positive and inspiring, at the same time it seems so out of time, reminiscent of the fifties, sixties, and the seventies, when there was such an unclouded, positive image of encounter, of social class distinction, as well as distinction between cultures, between young and old, and so on. I’m looking forward to the time when it radiates as an idea into the urban space again.

Nine Buildings, Stripped (Palast der Republik), 2019

anodized aluminum, solar control glass, marble, scraped sandstone, concrete, steel strapping band

Photo: Kunsthalle Wien / Jorit Aust

Study Desk (Susanne Kriemann photographing Ernst May, Magnitogorsk, Russia), 2016

plywood, wall paint, steel, spray paint, digital c-prints

Photo: Proyectos Monclova / Patrick López Jaimes

Kultur und Freizeit, 2007

Exhibition view, Ungarischer Pavillon, 52. Biennale di Venezia

Photo: Tihanyi-Bakos Fotóstúdió

Envelop (Pictures from the Life of Hungarian Transport and Telecommunications), 2019