The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

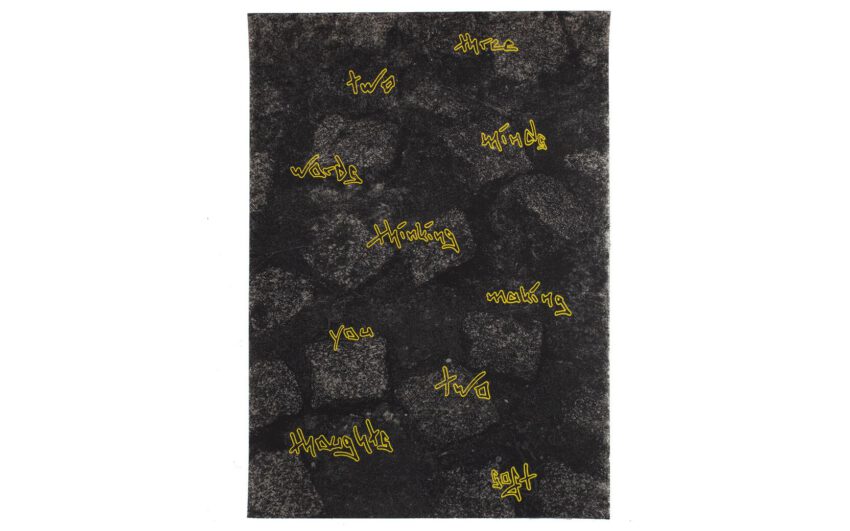

For over thirty years, Finnish artist Marianna Uutinen has been making works that reject the making of gestural marks in favor of an expanded notion of painting. She is best known for her large-scale abstract paintings made using her signature technique, which comprises building up layers of acrylic paint to make a skin and then draping these skins directly onto the canvas.

Marianna, you split your time between Helsinki and Berlin. How does that work on a day-to-day basis?

I’ve been in Berlin about six or seven years now, and from the beginning I wanted to keep studios in both places. This is an urban space and in Finland, where I still have a lake house, it’s more about nature. I need both, so this is the perfect arrangement for me.

So, both places have an important role to play for you.

I go back to Helsinki every month to live more my home life there. Whereas Berlin is a great working place and represents a place of freedom for me. Here I can put my work in another context and also free myself from materialistic living in a more ascetic way. For example, my flat is super minimalistic. There’s not much furniture around … I prefer light and space.

How would you describe your work?

It’s all about communication. I create a performative space that people can project onto. For instance, when I make these folds with acrylic paint people think that it’s real plastic. I seduce them into seeing something familiar, but not necessarily definable. The paintings are in the viewer’s experience, the result of a combination of material illusions and confrontations with the viewer’s own projections.

You just had an exhibition at Galerie Forsblom in Helsinki. What were some of the themes you were looking into?

It was called LIVE and with the title of the show I really wanted to suggest the idea that this materiality becomes alive, in a sense; that painting is a living image, a living thing, and is not only an object or a representation.

Can you elaborate on your method of working?

What’s the process of making the acrylic paint skins? I paint numerous acrylic layers thickly onto plastic and then detach the painted surface and glue it onto canvas. I mix color with lots of acrylic medium, which is plastic in its essence, and I use this material feature to create the illusion of plastic. I kind of like the paint to look like how it is.

One crucial thing in this procedure is that there’s this equality between the surfaces; the first layer of the painting is the oldest one. There’s this temporal equality because they’re all on the same surface. And I hope people experience the non-linear, the here and now.

How many layers does it usually take?

It depends on the surface of the individual painting and what I want, but the technical part is that it has to be at least four or five layers. You can imagine that if I make three paintings it can take up to 30 layers to get this effect. It’s a lot of material.

It must be quite physically taxing as well.

Partly, it’s a form of action painting, which makes it very physical – I have to paint on the floor and move big canvases around. There are quite a lot of uncontrollable aspects to this kind of working method, and it can be a real challenge to deal with. But the accidents can also produce some really good things. It’s part of the process. First you think, oh my god it’s destroyed, but then you have to accept that this material is so fragile and that it’s a part of the work.

There are obvious parallels that can be drawn between your method of working and Abstract Expressionism, which means that your work is often positioned as a female response to that, mostly, male-led movement. Is that how you see it?

Well I don’t think my painting methods are close to Abstract Expressionism per se, but I certainly have lots of references to this movement among other modernist languages in my work. I want my work to be open to many contexts. I’m a feminist myself, but I wouldn’t necessarily call myself a woman artist. It’s such a stereotypical and clichéd way of looking at my work, as if they [her series of works made with pink neon paint] were only about pink and that it must be about being a woman. Why should it be about women? Of course, it’s partly because I am a woman, but it’s not the main reason. I also heard from people about my paintings that you can’t tell if they were made by a man or woman, and I really love that because I don’t like gender categorizations in general. I hope it will happen one day that we don’t think so much in those terms.

When it comes to your studio practice, do you have a routine?

It depends on how I feel. I have periods where I have a routine and periods when I don’t, but it’s always in the back of my mind.

How long do you usually work on a painting for?

It can be the case that I work like a lunatic for four months [laughs] and then throw everything away because in the end I’m not satisfied, and then, all of a sudden, I make three paintings in two days. This “pre-work” is part of the process. I can also make one painting that takes four months to do, so it’s not really rational.

You’ve been practicing as an artist now for over 30 years. What kind of work were you making at the start of your career?

When I finished at the academy in ’85, I was making some kind of informal, very messy, abstract work with lots of materiality. I had a strong intuition when it came to painting, but I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to express. I just loved to paint. On the other hand, I was starting to follow art internationally and in these postmodern times I felt that I needed to find my own language and say something with my work.

Which artists were you looking at back then?

Everybody! The academy in Helsinki was very conservative academically: even though I had good artists and painters as teachers – and I think the dialogue I had with them was very important – we didn’t have any art theory or art history. I was lucky enough that I got to travel immediately after my school. It was fantastic, New York, Berlin… that was fantastic.

What came next?

I didn’t paint much for a few years. But I was still drawing and exploring things that interested me. I tried to read a lot of philosophy during that time– French post-structuralism, postmodern, semiotics – which opened up so much. I became more analytical, and free in my own work. I had my first show in 1989. An important historical moment for my whole career was making the work Cornucopia in 1989. It combines paint with a real object, a cornucopia, and it’s about the symbiosis between modernist painting and banal objects. I was painting with a cake decorator and imitating the texture of this banal object…the image and the real really merged the first time. I was very playful and ironic and had a lot of humor back then. I still have humor, but I don’t use it too much in my work anymore because life’s too hard [laughs].

Interview: Chloe Stead

Photos: Franziska Rieder