The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Heikki Marila’s work of more than twenty years has covered an extraordinary range of topics – from biblical motifs, self-portraits, wobbling vertical lines, floral paintings referencing sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Dutch still life painting, and maps of suburbia. His work has been inspired by the history of art, and in his recent paintings also by Lutheran Protestantism. Marila’s works are endowed with an extreme physicality that often conveys an exaggerated sense of drama and often irony. Sumptuous layers of paint conceal powerful social messages and sentiments. We sat down with Heikki in his Turku studio in the Southwest of Finland to discuss, among other subjects, his most prominent work cycle, his floral paintings, and his artistic contribution to the Finland’s one hundred year anniversary.

Heikki, your name is often associated with large-scale paintings of still lives of flowers. How come that you, as a contemporary artist, decided to dedicate yourself to such a conventional motif?

It was actually quite a long process for me to arrive at the flower paintings. Why did I want to paint flower paintings in the first place? Because the flower still life is one of the most popular subjects in art history. Probably every Finnish painter has painted flowers at some point in his career. The motif as such is quite mundane and today, especially in the contemporary art world, flower paintings are frowned upon as kitsch.

What was the igniting moment for you to begin your flower painting work cycle?

In 2004 or 2005, I decided that I had to paint flowers. I had come across the paintings of the Dutch masters of the sixteenth and seventeenth century, and something just snapped. I decided to paint these beautiful old master pieces my way.

What intrigued you about these old works laden with thick layers of oil paint?

You have to know that the traditional master works contained lots of details and symbols, carried many meanings, often political, which have often gone unnoticed to the inexpert viewer. Typically, such paintings were commissioned by affluent individuals who demanded from the artist that he included references to the wealth and societal status of their commissioner. My work has always included political dimensions or social messages. So this was something I was very interested in. I wanted to carry forward the principal idea of including details and meanings that become visible only upon intense study of the painting.

Heikki Marila, Kukat (Flowers) XV, 2009

Heikki Marila, Kukat (Flowers) XIX, 2009

Heikki Marila, Kukat (Flowers) XI, 2009

Is there a common misunderstanding with regards to your flower paintings? Just like their predecessors, in art history they might be easily dismissed as “kitsch” today.

When I started with the flower paintings, I intended to paint beautiful paintings in unconventional ways, provoking a contrast between the flower painting and the material. Having said that, it is important to note that I never painted flowers, but paintings of flowers on the basis of original flower paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth century masters, which makes all the difference. I’ve always tried to use existing forms as it gives me the freedom to explore the essence of a painting.

What details and messages are hidden in your contemporary versions of these flower still lives?

The details are created by the way I paint, by the process that becomes visible. Some patches look like dirt but they may also show a beautiful flower. In other words, the material is oil paint that renders different meanings depending on the way it is used. The act of painting involves a discussion between me, my time as well as things happening at a given period in time.

How did you arrive at oil as your material of choice, which until now has remained with you throughout your almost twenty-five year long painter career?

I already began to paint with oil in art school. Working with oil gives you more time to make changes and the color no longer changes while it dries. I was always interested in exploring the possibilities of oil paint as a material. The map paintings period that preceded the floral painting cycle was like a laboratory enabling me to test several ways of using oil paint. In my case it’s fair to say: first came the material and then I began to develop themes. I became preoccupied with the question: what can I express with this material? At first, I thought I would be able to continue to express the political subjects that I had expressed in my works created in the 1990s. However, I gradually abandoned this idea and allowed my painting to develop more toward the essence of painting itself. I was able to let go, focusing on the material. The material and the way I paint are intrinsically connected.

Can you describe what’s happening when you are in front of a canvas, about to apply paint?

I’ve been painting since 1988 when I went to art school, learning how to paint and to study myself. At that time, I’ve learned important things about myself that are still valid today, namely what kind of person I am and how my mind works when I paint: First the picture emerges in my head and then I approach the canvas. The process might take quite some time and imply turns and changes. The process evolves, more like a flow. However, usually I work rather quickly.

Your expressive, forceful way of applying the oil paint to the canvas has been previously described as “a struggle between the artist and the canvas”. Is it really such an intense and energy-consuming act as it appears in the final painting?

It might look that way, but it is never a struggle for me. It is more like a fun game to me, having fun playing with the material and the canvas. If it were a struggle I should probably give up painting. (laughs)

Which methods are you using to apply these thick chunks of oil paint to the canvas?

I was using my fingers and my entire hands when I began the period of flower painting. Prior to that, I had been working with brushes, silicon spades, and sticks. You can actually paint with anything. However, I felt that there was this gap between the canvas and myself. I felt, I wanted to enter into a more immediate and intimate contact with the material and the canvas. Using my hands felt like the natural thing to do for me.

How does one have to imagine a usual work day in your studio?

Well, I try to be here early, which means around 10 or 11 in the morning. (Laughs) I might start working immediately or contemplate on what I did the day before and decide how to take it from there. I don’t work according to a particular schedule. For example, during my flower painting work cycle I worked day and night, completing each canvas in one go, as long as the oil paint was liquid and I was able to manipulate it. In this case, the process imposed itself on my working schedule.

Honestly, when we entered, we had expected that your studio walls would be covered with floral paintings. As it turns out: there is no single flower painting up on the wall.

Sorry to disappoint you, but I painted my last flower painting in January 2012. (Laughs) Well, not quite: I actually did paint four flower paintings last year.

What about your solo exhibition Flowers and Devils which took place in Helsinki’s Taidehalli in 2014, until then your most comprehensive show.

The works on show in Flowers and Devils have all been completed between 1994 and 2014, including five flower paintings. It was great to see some of my paintings there that I hadn’t seen in ten years. Many works were loans from Denmark and Sweden, and of course from museums and private collections across Finland.

Is it correct to assume that you grew tired of pursuing the same subject over and over again and give in to collectors’ requests for yet another flower painting?

(Laughs) Am I fed up? I don’t think I am. But there are just a lot of other things that I still want to paint. So it is more a question about the available time. I may paint flowers in the future again, although perhaps not with the same intensity. Sometimes it is good to go back to something, after putting some months or years in-between during which you are able to focus on other things. Often, you find something new such as how to use the material, or what kind of (flower) paintings to use as a subject. In early 2017, I had an exhibition at the newly established branch of Galerie Forsblom in Stockholm, for which I adopted two still life paintings of fruit on silver plate by Abraham van Beyeren and Willem Claeszoon Heda, both Dutch painters from the seventeenth century, and made variations of each. There was quite an obvious and clear connection with the flower paintings, but already then I felt it was an evolution from my earlier work cycle.

Throughout 2017 the entire country has celebrated “One Hundred Years of Finland,” the centennial of Finland’s independence from Russia, involving a lot of collaborations with the country’s artists’ and creative scene. As one of Finland’s leading contemporary artists have you also contributed?

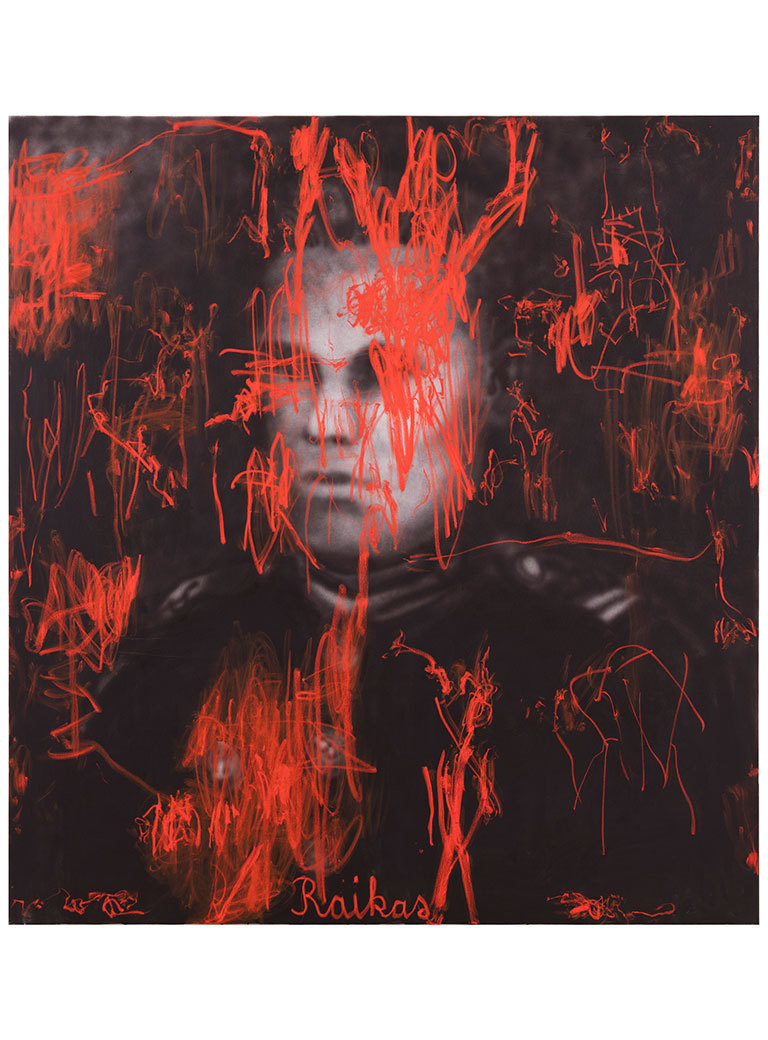

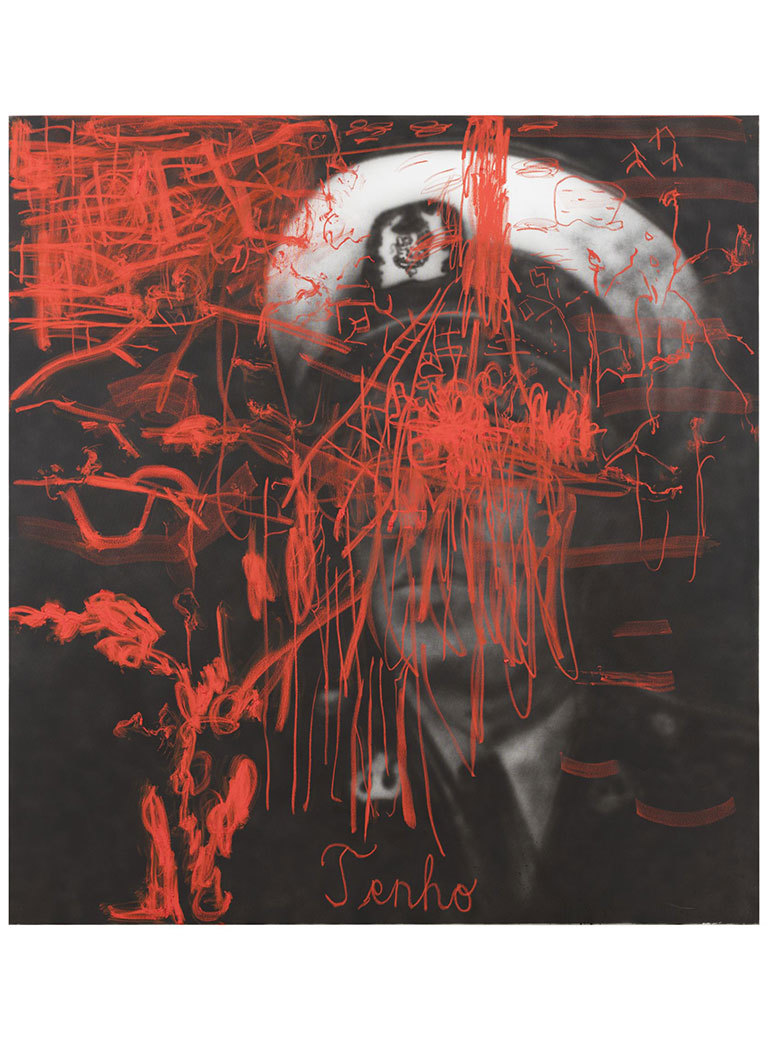

I have been asked to design the cover of the novel The Unknown Soldier, a matter-of-fact account of what it was like to be a low-level Finnish soldier in this hellish little corner of WW II, showing my grandfather’s portrait, painted from a portrait picture of him. It is this painting here in the center of the studio. Born in 1910, my grandfather was eight years old when he the civil war was raging in Finland, and he also fought in and survived World War II as a soldier. It is a continuation of a work cycle that I had begun in 2016, for which I used my family’s photo albums as subject of my paintings, which is something I had never done before. In every painting, I included a very personal “layer” as a backdrop in black-and-white. Then there is another layer in red, that is more common and abstract, that speaks to our collective memory in Finland.

What motivated you to open up the chapter of the Second World War and the Finnish Civil War on the occasion of “One Hundred Years Anniversary” of Finland?

I would say we have only misty memories from that time, and they are blurred by or restricted to random anecdotes. However, we still feel that pain as a nation and find it hard to talk about it. In January 2018 we remember the one hundred year anniversary of our Civil War that followed almost immediately after we had gained independence on December 6, 1917. It was an extremely brutal war between the so-called “Reds”, left wing fighters supported by Russia, and the “Whites”, supported by Germany, and it was one of the most terrifying wars in Europe according to accounts of people who were dying in captivity after the war. Compared to Germany where the trauma of the Second World War has been processed extensively not just in literature and movies, but also in contemporary art, Finland has not worked through this brutal war, at least not in the field of contemporary art. That’s why I feel that the “One Hundred Year Anniversary” is difficult for Finland. It is delicate, but important to confront.

Heikki Marila, Raikas, 2016; courtesy Heikki Marila and Galerie Forsblom

Heikki Marila, Tenho 2, 2016; courtesy Heikki Marila and Galerie Forsblom

You have mentioned Lutheran Protestantism as an influence to your work, which you understand as a kind of “operating system” of northern, and therefore also Finnish, culture. How is that?

In churches across Finland you find these old paintings, in which you can see the influence of artists from the Renaissance period. Local artists emulated the style of these old masters very clumsily, but the influence is obvious. Finland has been very reliant on external influence in regard to its artistic production. A strong influence came from France at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. For a long time, there existed no art schools in Finland. The earliest art school was established in Turku in 1835. Regarding my own work, the influence of German Renaissance painters such as Matthias Grünewald and Albrecht Dürer as well as the Neo-Expressionists has been very important.

How do you perceive the quality of art teaching in your country?

I see a big difference between the art educations today than when I went to art school in the late 1980s. I am a painter of the old school who has been trained in color theory and picture composition. In Finish art schools there is less time and space to truly acquire these basic skills, the tendency goes towards art theory. I wouldn’t call it a bad thing, but the difference between myself and these young artists who are emerging from art school is big. But perhaps it’s good to give up some things, to accept change.

You came originally from Lahti, in the South of Finland. What brought you to Turku?

I left Lahti when I was twenty-two and studied in Turku. After that, I moved to the small town of Hyvinkää, which was closer to Helsinki. I kept moving in the area a couple of times. It was important for me to stay in touch with the art scene to follow the events that were taking place in Helsinki, Finland’s cultural center. However, I always wanted a big studio, which would have been quite costly in Helsinki. In 2010, my wife and I decided to move back to Turku. Compared to Helsinki, Turku is a small town, but it has a vital art scene.

How do you relax or get new inspiration?

I do a lot of things in fact. I love classical music, reading books, visiting exhibitions… And I find time to travel to see art outside Finland. Last summer I went to see the documenta 14 in Kassel and the Venice Biennale.

Talking of passions other than painting, I could not help noticing that about a third of your studio surface serves as some kind of bike fixing workshop. Are you sharing the space with a bike buff or is this another passion of yours?

Oh, no no. The bikes are all mine. (Laughs) I started road cycling in the early 1980s as a hobby, buying my first Nishiki Roadmaster in 1983. From then on, I kept on cycling – sometimes more, sometimes less. Bikes are just nice. At the core, bikes have principally not changed through the years, but new materials and fascinating technological advancements arrive constantly. I am fascinated by technology in general, not just bikes, so I got hooked.

Visitors to your website can watch a time-lapse film featuring you painting and cycling around your studio space in circles in shifts, like a mad-man. Is this how one has to imagine Heikki Marila at work?

(Laughs) One may easily get this kind of impression, but no. I probably work a bit more focused than that. But I do find it important to be allowed to be doing other things when I am in the studio. For me, a studio should be a place where one likes to spend time and can do the kind of things one wants to do that mustn’t necessarily be art.

What will the year 2018 bring for you?

A lot of work. I hope it is going to be another exciting year.

Photos: Florian Langhammer

Interview: Florian Langhammer